Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kīhei de Silva

Haku mele: Kīhei de Silva (words, 11-1988). Louis "Moon" Kauakahi (music, 11-1990).

Discography: Discography: The Mākaha Sons of Ni‘ihau, Ho‘oluana, 1991, SPC 9049.

Hā‘ale ke aloha no Hōnaunau

Ke nā‘ū nei kamali‘i i ka lā

Ka lā kau aku i Pōhaku-Nānā

E hi‘i ‘ia maila e Moanauli

Huli aku nānā i ka lei maile

Lana i ke ala loa a ka wāwae ‘ehu

‘Ehuehu ke alo i ‘Akahi-Papa

E hihi mai ana e ka lihilihi

Hō‘ihi ka inoa ‘o Pi‘ilani

‘Ikea nō ka hiwa mai lalo Kona

I am filled with love for Hōnaunau

Where children chant nā‘ū to the sun

To the sun that rests above Pōhaku-Nānā-Lā

To the sun held in Moanauli’s embrace

Look back, turn to the lei maile

Afloat on the long path of faded footsteps

At ‘Akahi-Papa the face is damp with sea spray

And the eyelashes are salt-encrusted.

We hold in reverence the name Pi‘ilani

Known is the precious one from lalo Kona.

Program notes for the 1993 Punahou School May Day Program identify this song as having been "written for Hawai‘i’s chief ‘O Pi‘ilani; the writers extend their aloha for Hōnaunau, Pōhaku-Nānā, Moanauli, ‘Akahi Papa, and Kona, all in the name of chief Pi‘ilani." Although I was honored by Punahou’s good taste in Hawaiian poetry and music, I would have appreciated an opportunity to explain that the song was not written for chief "‘O Pi‘ilani" of the Big Island (or Maui, or Ireland, for that matter) but for my mother Lorna Pi‘ilani de Silva, a native of Hōnaunau, Kona Hema, Hawai‘i, the district whose place names are celebrated in the first, second, and fourth verses of her mele.

As a result of Moon’s appealing music, Mom’s song has been danced all over the place: in at least four hula competitions, in a Miss Kona beauty pageant, and in a fistful of high school, intermediate, and elementary May Day programs. We’ve even stumbled upon a disappointing East Coast hula workshop version of "He Inoa no Pi‘ilani" (taught by an O‘ahu kumu who probably thought he was far enough away to escape our notice) that has infiltrated various D.C.-area functions. What amazes us about the majority of these performances is that they are merely music-inspired dance routines whose motions reflect, at most, a liner-note-only understanding of the text and whose spirit connects to the poem’s meaning in only the most superficial of ways. What amazes us even more is this: although we are very willing to share the song and its meaning with anyone who expresses a genuine interest, almost no one bothers to ask. Of all the "He Inoa no Pi‘ilanis" now taught, danced, and sung outside our hālau "network," only one belongs to a kumu hula who called us for permission and information: Aunty Joan Lindsey.* And only one belongs to a group that actually invited me to talk about the mele: the 1992 second graders of Kaua‘i’s Wilcox Elementary School. For only these two—for the performances of the Lindsey and Wilcox kids—did my mother "show up." Their choreographies differed considerably from each other and our own, but both sets of students danced from the piko; both knew what they were doing on a level far more significant than that measured in the precision of gesture-step-smile. Consequently, it was easy for me to see Mom in their hula.

Mom died in February 1987. We scattered her ashes at Hōnaunau. Our extended family had last gathered there two Thanksgivings prior to this. After her death, our memory of that happy gathering led to my own little family’s decision to set aside every subsequent Thanksgiving Day for remembering her. We remember by visiting and creating. I composed "He Inoa no Pi‘ilani" at the first of these Thanksgiving visits and "Aia i Hi‘ikua i Hi‘ialo" at the second.

The song’s first verse opens with words reminiscent of a pair of ‘ōlelo no‘eau: "Hā‘ale‘ale i ka pu‘uwai – A heart full to the brim" (#392) and "Hā‘ale i ka wai a ka manu – The rippling water where birds gather . . . the rippling water denotes a quiet peaceful nature which attracts others" (#393). My own hā‘ale is meant to express a quiet brimming-over of love for a place and person whose serenity is now a constant attraction.

The verse concludes with a reference to nā‘ū, the children’s chanting game described in "‘O Kona Kai ‘Ōpua i ka La‘i." My nā‘ū is meant to evoke the same sense of serenity (the life-bringing promise of rain-bearing horizon clouds, the peace of children at play, and the warmth of a land that loves and is loved by its ali‘i) evident in the older mele. It is also meant to remind me that I was far less willing, 45 years ago, to participate in this idyllic scene. Back then, I thought of nā‘ū as a form of child abuse inflicted by my mother on her uncooperative and suspicious sons. During family summer vacations in Kona (we were raised in Hilo), my brother and I were required, at sunset, to lie with our heads over a placid, Hōnaunau tide-pool. When the bottom of the sun touched the horizon, we inhaled mightily and attempted to chant "nā-ū-ū-ū-ū-ū" on that single breath, without disturbing the tide pool’s surface, until the sun disappeared completely from view. "Why," we would grumble, "does she always have to make up these stupid games?"

It was only as an adult, several years after her death, that I researched "‘O Kona Kai ‘Ōpua," read Kawena Pukui’s and Tom Maunupau’s descriptions of nā‘ū, and discovered that I had been playing a traditional chanting game of Kona and Ka‘ū whose purpose was to teach breath control to children and whose goal, in some versions of the game, was to keep the sun from setting: "It will hang in the sky," children were assured, "for as long as you can hold out your nā-ū-ū." For me, the game has come to stand for two things: the stubbornness that kept me, too long, from appreciating Mom’s knowledge, and the wholehearted effort I now make to keep the sun in the sky.

The song’s second verse begins with a reference to Pōhaku Nānā Lā, a partially submerged boulder on the lava flats to the west of Hale o Keawe. At the right time of day (according, again, to Mom), kids used to dive under the boulder, look through the narrow passageway formed by a concavity in its underside, and enjoy a kind of kaleidoscope view of a water-filtered, shimmering green sun—hence the name "Rock-Observe-Sun." Again, it was only as an adult that I came across Stokes’s 1919 account and photograph of Pōhaku Nānā Lā. His description matches my mother’s; his photograph even shows the feet of a submerged boy who "obligingly demonstrated the [game]" (Bryan and Emory, The Natural and Cultural History of Hōnaunau, Kona, Hawai‘i, 197–8).

The second verse ends with the song’s third reference to the sun—this time to its being held in Moanauli’s embrace. Moanauli (dark ocean) is the name of one of Mom’s grandfathers, several generations distant, who was born in Wai‘ōhinu, Ka‘ū in 1799. It is, in part, through Moanauli’s line that Mom’s family served the senior chiefs of Hōnaunau, tended to their repository at Hale o Keawe, and later assumed similar duties at Mauna ‘Ala. The image of a sun seen through Pōhaku Nānā Lā and held by Moanauli is thus meant as a figurative expression of continuity and legacy. The child on one side is connected to the grandparent on the other by means of the parent who provides the "lens" by which the former can know the latter.

The song’s third verse is written straight from memory. When we scattered Mom’s ashes, we left lei maile in the water and watched one float, at sunset, past the cove and inner reef, and out into the deeper water of the bay. In my mind, at least, the lei kept on going, and as it went, it seemed to leave a faint trail of still water to mark its passing. I thought then, and continue to think now, that the lei was Mom on her journey to God. She was borne on that path by the gentle embrace of her ancestors while we, the no longer reluctant nā‘ū chanters, bore witness on this side of Pōhaku Nānā Lā. We now occupy Mom’s old spot in this sequence, and "He Inoa no Pi‘ilani" is the lens I hold up for my own children to help them keep Tūtū in view.

‘Akahi Papa is the name of the half-submerged lava tongue jutting into the ocean from the northeast corner of Hale o Keawe and connected to the shore at low tide. "It is known as the place where refugees could land after swimming from the rock Pu‘u o Ka‘ū, across the bay. On it a tall spear is said to have been set up from which a white flag flew to mark the entrance to the pu‘uhonua" (Stokes, in The Natural and Cultural History of Hōnaunau, 167). The fourth verse of "He Inoa no Pi‘ilani" describes the damp, salt encrusted face of the actual gateway to sanctuary, but the full meaning of the passage depends, as well, on the haole meaning of Papa. The image I hold in my memory is of my father standing at Pu‘u o Ka‘ū and looking across the water to ‘Akahi Papa, his lashes coated with the salt of sea spry and dried tears. I touched him and, in so doing touched Mom, and in so doing found that our pu‘uhonua was still in place.

The closing verse of "He Inoa no Pi‘ilani" is meant to echo lines 249–50 of "Ka Inoa o Kūali‘i," a name chant for the preeminent chief of 17th century O‘ahu: "‘Ikea ka hiwa mai lalo Kona / ‘O ka hiwa ia mai lalo Kona – Known are the sacred things from beneath Kona / It is the precious one from Kona’s foundation" (Fornander, An Account of the Polynesian Race, II:271–399). Kūali‘i’s chant devotes over a hundred lines in its own closing section to extolling his superiority; nothing on land, sea, or sky can compare to him; he is not like the hala, ‘ōhi‘a, or ‘a‘ali‘i; nor is he like the porpoise, shark, or līpoa; nor is he like the ‘ō‘ō, nāulu rain, or mountain wind. He can be compared to one thing only, the chant finally concedes; he finds an equal in his Hawai‘i island counterpart, the Hōnaunau-based chief Keawe‘īkekahiali‘iokamoku:

Ua like; aia ka kou hoa e like ai,

‘O Keawe‘īkekahiali‘iokamoku,

‘O Keawe, haku o Hawai‘i

There is a comparison, here, indeed, is the one you resemble

It is Keawe‘īkekahiali‘iokamoku

Keawe, lord of Hawai‘i.

(Polynesian Race, II:384, lines 583–585; my translation.)

This Keawe is the ali‘i for whom Hale o Keawe was built and to whose reign was ascribed "such peace and prosperity as the island of Hawai‘i had not enjoyed since the time of his ancestor Līloa" (Barrere, Tracing the Past at Hōnaunau, 9). Although "‘ikea ka hiwa mai lalo Kona" appears much earlier in the Kūali‘i chant than does the homage to Keawe, the "hiwa" passage strikes me as a highly appropriate reference to Keawe and his sanctuary: they formed the much-esteemed base on which Kona stood and thrived. For me, the "hiwa" passage is also a highly appropriate description of Mom: she is the precious foundation on which our family stands and from which we derive an unshakable sense of identity, purpose, and continuity. The Keawe, Hōnaunau, and Pi‘ilani bases, moreover, are ultimately one. Keawe‘īkekahiali‘iokamoku was one of the 23 Keawe-line chiefs tended to at Hōnaunau by a junior line of the same family: my mother’s. That relationship has tied us to Hōnaunau for over three centuries; it mandates, even now, a lifestyle whose focus is the providing of care, sanctity, and refuge. Thus in honoring Pi‘ilani, we reaffirm our link to those who precede her and find ourselves still meaningfully connected to the kulāiwi and kuleana of her ancestors.

The essay above was written by Kīhei de Silva and published in his book He Aloha Moku o Keawe: A Collection of Songs for Hawai‘i, Island of Keawe, Honolulu, 1997, pps. 33–36. It is offered here, in slightly revised and updated form, with his express consent. He retains all rights to this essay; no part of it may be used or reproduced without his written permission.

* Cody Pueo Pata, who asked for permission and explanation in 2004, is the second teacher to observe this courtesy.

photo courtesy of: Kīhei de Silva

A young Lorna Piʻilani de Silva, kupa of Hōnaunau.

photo credit: de Silva family collection

Lorna and Edwin de Silva Jr., Honolulu, 1946. “Home from Berkeley for Christmas.”

photo courtesy of: Kīhei de Silva

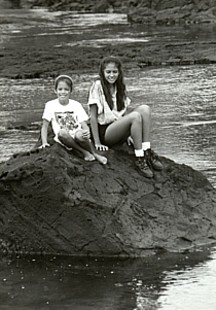

Pōhaku Nānā Lā me nā pua a Moanauli, ‘o Kapalai lāua ‘o Kahikina de Silva.