Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kīhei de Silva

Haku mele: The warriors of the Kīpuʻupuʻu.

Date: ca.1785.

Sources: 1) Mele Book of B. Namakeha, HI.M.63:29–37, 147, 205; Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum Archives. 2) Kapiolani-Kalanianaole Collection, HI.M.42:41; BPBMA. 3) Mele Book, HI.M.61:34; BPBMA. 4) He Buke Inoa I.A. Liholiho, HI.M.60:152; BPBMA. 5) Kuluwaimaka Collection, HI.M.51:91 (Bk.1) and audio Haw 2.1.17, 2.2.14; BPBMA. 6) Mader Collection, MS Grp 81, 3.40; 81, 8.13; 81, 8.14; 81, 8.20; and 81, 9.38; BPBMA. 7) Roberts Collection, MS SC Roberts 5.2:33b–34 and 5.3:51; BPBMA. 8) Nathaniel Emerson, Unwritten Literature of Hawaiʻi, 68–9.

Discography: Nā Leo Hawaiʻi Kahiko, 1-A-9, Department of Anthropology, BPBMA.

Text Below: Mary Kawena Pukui, handwritten text and translation, in Mader, MS Grp 81, 8.13; BPBMA.

Hole Waimea i ka ihe a ka makani,

Hao mai na ale a ke Kipuupuu,

Laau kalaihi na ke anu,

Oo i ka nahele o Mahiki.

Ku aku la oe i ka malanai [1] a ke Kipuupuu,

Holu ka maka o ka ohawai [2] o Uli [3],

Niniau, eha ka pua o koaie [4],

Eha i ke anu ka nahele o Waika e,

Aloha Waika iaʻu me he ipo la,

Me he ipo la ka maka lena o ke koolau [5],

Ka pua i ka nahele ma Huleia [6],

E lei hele i ke alo o Moolau [7],

E lau ka huakai hele i ka pali loa,

Hele hihini, pili noho i ka nahele,

O kuu noho wale iho no i kahua e,

O kou aloha kai hiki mai i o’u nei,

Mahea la i nalo iho nei.

Waimea is tousled with shafts of the wind,

While the Kipuupuu puffs in gusts,

The trees are blighted by the cold

That drives through the forest of Mahiki.

You are pierced by the cold Kipuupuu wind

That sets the ohawai blossoms asway,

Wearied and bruised are the flowers of Koaie,

Stung by the frost is the herbage of Waika.

Waika loves me like a sweetheart,

Dear to me are the yellow centered koolau blossoms,

The blossoms of the forest of Huleia,

That are worn in wreaths at Moolau,

Travel-wreaths for travelers on a long climb

To our homes in the wilderness,

Still do I cherish our old home,

For your love still visits me here,

Where have you been hiding till now?

Mary Kawena Pukui’s definitive explanation of "Hole Waimea" appears in the liner notes that accompany Kuluwaimaka’s kepakepa rendition of the mele on the Bishop Museum LP Nā Leo Hawai‘i Kahiko. Pukui identifies the Kīpuʻupuʻu warriors of Waimea as the haku of this composition; in it, they honor their aliʻi Kamehameha and describe their spear-making activities in the forest of Mahiki:

Kamehameha needed more spear fighters and having heard of a company of twelve hundred young men of Waimea, Hawaii, who were trained runners, he went to see for himself. He was pleased with their swiftness and knew that they would make excellent spear fighters. He appointed Na-nuʻu-a-Kalani-‘ōpuʻu to train and lead them. They called themselves the Kipuʻupuʻu after the icy cold rain of their homeland. The first thing they did was to go to Mahiki forest to make spears. It was there that the young men thought of composing a chant in honor of their chief, Kamehameha I. The first composition was criticized by several expert poets and hula masters. It began with ‘Hole Waimea i ka ihe a ka makani, hala kika i ka puʻukolu.’ (Waimea is pierced by the spear-like blasts of the wind; slipping and sliding over the triple hills.) It was the slipping and sliding that was objected to. With the few changes, the chant was completed to the satisfaction of all and presented as a gift to the ruler by [his] newly trained warriors of Waimea. It was first chanted as an oli and later, as a hula. This was one of the most popular chants of Kamehameha’s day and was heard wherever his armies moved [8].

Pukui’s explanation stands in marked contrast to Nathaniel Emerson’s typically disjointed preamble to "Hole Waimea," one that includes a criticism of the mele’s "comparative effeminacy and sentimentality of style" and a half-hearted defense of its intensive use of "euphemism and double entendre" [9]. Effeminacy and sentimentality are, in fact, rampant in Emerson’s translation of the text, but are entirely absent in the powerful, image-rich language of the original. Euphemism and double entendre, moreover, are Emerson’s comparatively effeminate expressions for the highly valued kaona of Hawaiian composition—the kaona, in this case, of lovemaking.

Ku aku la oe i ka Malanai a ke Kipuupuu

Emerson: Smitten art thou with the blows of love

(You are pierced by the Malanai and Kīpuʻupuʻu)

Nolu ka maka o ka ohawai o Uli

Emerson: Luscious the water-drip in the wilds

(The ‘ōhāwai blossoms of Uli give way) [10]

Stephen L. Desha offers a prudent but considerably less squeamish account of the lovemaking undercurrents of "Hole Waimea." He explains that the Kīpuʻupuʻu took "chiefly women" with them on their Mahiki expedition, that the mele’s reference to spear stripping has a hidden meaning, and that this kaona is ours to figure out. Where Emerson protests, wrings his hands, and slips us—in his footnotes—the "sordid" details; Desha simply explains the situation and, in matter-of-fact fashion, leaves the rest to us.

There is a hidden meaning in this old mele, as that forest of Mahiki was a place for making spears for the warriors in ancient times. In times of peace, the aliʻi and the men would go there to prepare for the times of war to come.

When Kamehameha was staying at Kawaihae, he went with his many warriors to that forest for the making of spears. Some of his court accompanied them, in other words, the chiefly women. At this place of the story, the writer conceals the hidden meaning of the "Stripping of Waimea by the spear of the wind" and it is for the reader to guess the meaning. [11]

Desha’s Kekūhaupiʻo also provides several glimpses into the history of the Kīpuʻupuʻu. He explains that many of these men were the children of the warriors of the ‘Ālapa and Pipiʻi battalions of Kalaniʻōpuʻu, "men chosen from amongst the chiefs of . . . Hawaiʻi, half of them . . . from the famous land of Waimea" [12]. He explains that the Kīpuʻupuʻu were trained in war by Kekūhaupiʻo and Nanuekaleiōpū [13] and that this training placed considerable emphasis on running:

It was said that they continually practiced in preparation for warfare and in body strengthening. This army...was accustomed to running...Their alertness was known and they were well able to pursue enemy who fled from a battlefield. And they were alert in running to places where their assistance was desired. [14]

Desha identifies the battle of Laupahoehoe II—ca. 1875 [15]—as the first in which the Kīpuʻupuʻu were involved. They were led to Hāmākua by Nanue, where they joined with the Kamehameha-led Mālana and engaged the warriors of Keawemaʻuhili at Kupapaulau. Although they had no combat experience, the Kīpuʻupuʻu fought fearlessly, handled their weapons with "incomparable skill," and pursued the enemy with "great liveliness." After two day of fighting, they prevailed over the "yellow backed crabs [swift, strong warriors] of the straight cliffs of Hāmākua and Hilo Palikū" [16].

The other battles in which Desha specifically refers to the Kīpuʻupuʻu are those of Kepaniwai [17], Mahiki, Pāʻauhau, and Koapapa. The last three of these were fought in a Waimea-to-Hāmākua sequence in the summer of 1790 in response to Keōuakūʻahuʻula’s plundering of Kamehameha’s lands in Waipiʻo, Waimea, and Kohala while Kamehameha and his warriors were in Maui and Molokaʻi. When Kamehameha received word of Keōua’s atrocities, he returned to Kawaihae, pursued Keōua to Waimea, fought through an ambush at Mahiki, and defeated the invaders in two bitterly fought battles along the seacliffs of northeast Hawaiʻi [18]. The Kīpuʻupuʻu—whose homeland bore the brunt of Keōua’s abuse—figured prominently in this pursuit and conflict. It is my contention, in fact, that the mele "Hana Waimea i ka ‘Upena a ka Makani" describes the Kīpuʻupuʻu as the "leading edge" of the net of wind that entangled and cast Keōua from this Waimea homeland. Together, the mele "Hole Waimea" and "Hana Waimea" constitute something of a poetic before-and-after. In the first, the Kīpuʻupuʻu gather at Mahiki to make spears and love. In the second, they pursue the enemy through Mahiki with those same spears and in defense of those same loved-ones.

Dorothy Barrere hypothesizes that "Hole Waimea" was composed during one of Kamehameha’s two extended stays at Kawaihae and Waimea: in 1791–92 "when the building of the heiau at Puʻukoholā necessitated the support of a large body of workers," or in 1794–95 "at the time of the preparation and staging of the peleleu fleet that carried [Kamehameha’s] wars across the sea to Maui and Oʻahu" [19]. In light of the Pukui and Desha accounts reviewed above, neither of Barrere’s dates makes much sense; they occur a decade too late in the history of the Kīpuʻupuʻu. Pukui clearly indicates that Kamehameha appointed Nānuʻuakalaniʻōpuʻu to train the Kīpuʻupuʻu in spear fighting and that the "first thing they did was to go to Mahiki forest." If Desha’s account is accurate, the Kīpuʻupuʻu fought their first battle for Kamehameha at Laupahoehoe II in about 1785, and by 1790 had become the battle-hardened "ʻalihi pīkoi" that cast Keōua from Waimea. This means, then, that "Hole Waimea" had to have been composed before Laupahoehoe II; the Kīpuʻupuʻu could not have made their first spears in Mahiki in the 1791 and 1794 time-slots proposed by Barrere.

Vivienne Mader’s notes to the five versions of the mele collected from Kuluwaimaka, Pukui, Beamer, Laʻanui, and Erdman identify the chant as belonging to an even earlier period: to the "time of Kalaniopuʻu ruler of Hawaii when Captain Cook came" [20]. I have found nothing that corroborates Mader’s pre-1773 date of composition (Kalaniʻōpuʻu died in 1772), but it suggests that my Desha-based estimate of 1785 might actually be middle-of-the-road.

Pukui explains that "Hole Waimea" enjoyed great popularity in its day. One consequence of its appeal can be found in the number of companion mele that it apparently inspired. Two of the older chant books in the mele manuscript collection of the Bishop Museum Archives present "Hole Waimea" as the first paukū of a 14-paukū composition [21]. Of the 13 additional paukū, the seventh, "Hoe Puna i ka Waʻa," is still performed today—often in a version that combines portions of "Hole Waimea" and "Hoe Puna" into a single text [22]. The others, however, are unfamiliar (to my eyes, at least). They range across the island chain in non-geographic succession [23], each is attributed to a different haku mele [24], and each is loosely patterned—in length, phrasing, and sentiment—after "Hole Waimea." All of these paukū are worthy of contemplation and research, as is the nature of their relationship to each other, their order in the larger piece, and the guidelines of the common "assignment" by which they seem to have been generated.

None of this, of course, lies in the scope of my present study; I advance these thoughts in an effort to demonstrate the depth, wealth, and unexplored nature of so much of the literature that we foolishly take for granted. The "Hole Waimea" that most of us think we know is merely the tip of an iceberg, a koʻa manō projecting above the reef below.

Notes:

© Kīhei de Silva 2006

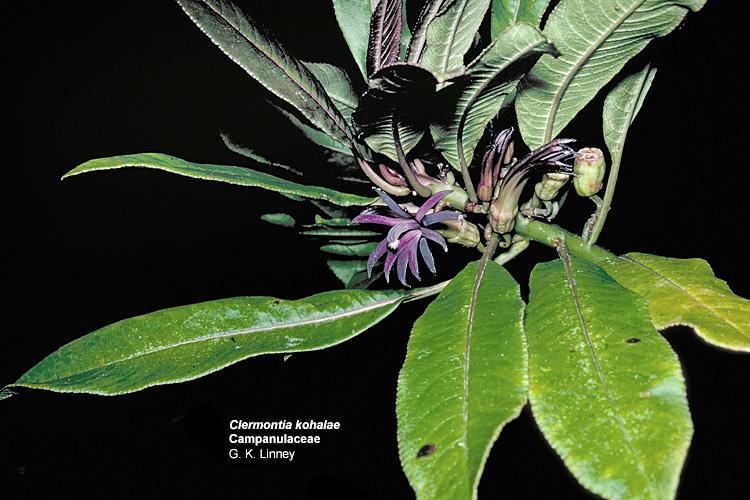

photo credit: G. K. Linney

The native ʻōhāwai (Clermontia kohalae) of Waikā forest grows as a tree or shrub, with flowers curved like the beaks of the honeycreepers that feed from them.

photo courtesy of: Baker-Van Dyke Collection

James Palea Kapihenui Kuluwaimaka, perhaps the greatest chanter of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. According to Theodore Kelsey, Kuluwaimaka’s great-grandfather was very close to Kamehameha I and fought with the warrior chief in battles at Hāmākua and Hilo Palikū. Kelsey calls Kuluwaimaka "a singing man... [He] chanted for Queen Emma. She retained him and after her death he became chanter to King Kalakaua, and after Kalakaua’s death he retired to his home and married three times to professional hula women" (Elizabeth Tatar, Nineteenth Century Hawaiian Chant, iii).