Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kīhei de Silva

My wife, Māpu de Silva, learned "No Luna i ka Hale Kai no ka Ma‘alewa" from Maiki Aiu Lake in May 1974. As was her custom, Aunty Maiki wrote the Hawaiian text on the chalkboard, added an abbreviated English translation [1], and directed her class, the Papa ‘Ilima, to Nathaniel B. Emerson’s Unwritten Literature for background information. Maiki apparently recognized Emerson’s limited understanding of "No Luna" and advised her students to go beyond his UL gloss by studying the Hi‘iaka legend and researching, for themselves, the mele’s person- and place-names. Māpu does not know if anything came from her kumu’s suggestion; the class was probably too busy learning "No Luna" to learn more about "No Luna," and Māpu remembers no further, in-class discussions of the mele.

Aunty Nana (Maiki’s cousin and hula sister, Lani Kalama) was a keeper of the same version of "No Luna." According to Māpu, "Aunty Nana always picked it when she wanted me to dance; Aunty would chant and I would dance. Because ‘No Luna’ was a favorite of hers, I danced it regularly in the ’80s and ’90s—right up until her death in January 2000. As a result, I’m very sure of the dance. Aunty didn’t let me put it aside." We know that Maiki and Nana learned "No Luna" from Lōkālia Montgomery as part of their 1946 ‘ūniki repertoire, but we don’t know who taught it to Lōkālia. Its motions are too big for the Kaua‘i-style hula of Keahi Luahine and Kapua, so we have to rule out the Keahi-Kapua-Kawena connection [2]. It might be from Hawai‘i Island, maybe from Kawena through Joseph ‘Īlālā‘ole, or perhaps Lōkālia learned it from Keaka Kanahele, another of her teachers. We don’t know.

In our 30 years of working with "No Luna," we’ve examined quite a few variant texts of the mele—seven, at last count. Most offer a kind of swooping, zoom-lens description of Puna, Hawai‘i, as we travel there, across the ocean, from the high sea cliffs of Kaua‘i’s north shore. We begin at Kahalekai and Kama‘alewa where we note the presence of Moananuikalehua (goddess of the channel between Kaua‘i and O‘ahu) on a distant, lehua-lined shore. We take a close-up look at Hōpoe, the lehua/woman who fears the predations of blossom-hungry men. And we listen to the rough surf of Puna as it rattles the beach pebbles and echoes in the hala groves of Hōpoe’s homeland. The Lōkālia and ‘Īlālā‘ole texts end with this description of "kai ko‘o Puna." Several other versions (Emerson and Helelā, for example) provide a more personal conclusion to the mele; they invite a reluctant companion to: "Move close to me, beloved / Don’t turn away / The cold is a bad thing / There should be no cold / We shouldn’t behave as if we were outside / With our skins soaking wet" [3].

Although we’re inclined to agree with Emerson’s suggestion that these longer versions are characterized by a shift in tone that "sound[s] like a love song [and] may possibly be a modern addition to the old poem," we can’t be sure of the relative age of the short and long versions [4]. What we are sure of is this: all versions, both short and long, are old enough to be well outside our ‘ōlelo comfort zone. There are passages in each where we labor over possibilities, juggle interpretations, wrestle with ambiguities, and itch to make "little" corrections. Their diction, orthography, agrammatical structures, and textual discrepancies mark them all as pre-western, as transmitted orally over many generations, and as belonging to several discreet and valid hula traditions [5]. "No Luna," unlike "Aia lā ‘o Pele" [6], is a tree with many branches whose trunk and taproot are, as Aunty Pat Namaka Bacon is fond of saying, "lost in antiquity."

Emerson’s backstory for "No Luna" is minimal. He attributes the mele to Hi‘iakaikapoliopele and her companion Hōpoe, but he correctly points out that the mele’s internal evidence contradicts his informant’s belief that it was "a mele taught to Hi‘iaka by [this] friend and preceptress in the hula" [7]. It can’t have been taught to Hi‘iaka by Hōpoe because it is quite obviously Hi‘iaka who gives voice to the poem and Hōpoe who is its focus.

Because Emerson’s explanation of the related mele "Kua Loloa Kea‘au i ka Nahele" immediately precedes his presentation of "No Luna" it is easy to misread the "Kua Loloa" explanation as belonging to "No Luna": This poem is taken from the story of Hiʻiaka. On her return from the journey to fetch Lohiʻau she found that her sister Pele had treacherously ravaged with fire Puna, the district that contained her own dear woodlands. The description given in the poem is of the resulting desolation [8].

A close reading of the two mele, however, clearly indicates that the fire-ravaged woodlands and emotional desolation of Emerson’s gloss refer to the former composition—to "Kua Loloa"—and not to the latter. There is no apparent devastation in "No Luna"; the lehua still bloom on Puna’s shore, and the beautiful Hōpoe has not yet been reduced to ash and transformed into a water-dancing stone.

The context of "No Luna" suggests that it occurs earlier in Hi‘iaka’s journey, probably in the initial stages of her return from Kaua‘i with Lohi‘au. The vantage point from which Hi‘iaka gives voice to the mele is "from above" (no luna) "at the sea house" (i ka hale kai), "from the aerial-root vine" (no ka ma‘alewa). Emerson tells us that Lōkālia’s "hale kai" is the place-name Halekai (or, perhaps, Kahalekai): a "wild mountain glen" at the back of Hanalei Valley [9]. Other versions of "No Luna" (most importantly the Pukui-translated ‘Īlālā‘ole text) treat Lōkālia’s "ka ma‘alewa" as another high-elevation place-name: "Up on the house-like summit of Kama‘alewa" [10]. The two names (as far as we know) are not remembered today; they don’t appear on old maps, in other chants, or in the usual place-name resources. In the absence of additional information, corroborative or otherwise, we’ve made the assumptions (as reflected in our translation of Lōkālia’s text) that "ka hale kai" and "ka ma‘alewa" are, indeed, Kahalekai and Kama‘alewa, and that both sites are, in fact, high on the cliffs of Kauaʻi’s north shore where Hi‘iaka brought Lohi‘au back to life.

Tradition tells us that Hi‘iaka was blessed with far-sight. She was able to look down the island chain to her Kīlauea home, and she sometimes monitored, from high places on Kauaʻi and O‘ahu, the activities of her jealous sister and the well-being of her friend Hōpoe [11]. "No Luna," we think, is one of Hi‘iaka’s far-seeing, check-up chants. As Hi‘iaka gazes across the sea in the first section of our Lōkālia text, she first observes Moananuikalehua [12], guardian of the ‘Ie‘ie Channel that lies between Kaua‘i and O‘ahu. Moananui was a contemporary and traveling companion of Pele; the two came together from Kahiki, and Moananui (at least according to Emerson) is now unhappy over the prospect of Pele’s inappropriate union with Lohi‘au, a mere mortal [13]. Moananui had earlier raised surf and storm to make it difficult for Hi‘iaka to cross from O‘ahu to Kaua‘i; Hi‘iaka seems to be checking on her here, in "No Luna," to gauge the difficulties of the journey home. In several other versions of "No Luna," Hi‘iaka addresses Moananui with a request to calm the seas: "Noi au i ke kai e maliu – I ask the sea to look kindly (on me)." In Lōkālia’s text, we have, instead, a "coast-is-clear-for-now" description of the demigoddess in repose on the lehua-lined sea-shore of Look-Kindly [14]: "Noho i ke kai o Maliu / I kū a‘ela ka lehua i laila."

The sense of foreboding that plays faintly at the edges of the first section of Lōkālia’s "No Luna" takes a more prominent role in the mele’s second paukū. Hi‘iaka chose duty over friendship, Pele over Hōpoe, when she agreed to take up the quest for Lohi‘au. She knew from the outset that Hōpoe would be the initial victim of Pele’s wrath should the journey take too long or otherwise fall short of Pele’s expectations. For this reason, Hi‘iaka has made a deal with Pele: I will only go if you guarantee the safety of my friend and our lehua groves. It comes as no surprise, then, that Hiʻiaka’s vision now narrows from the generic "lehua i laila" to the specific "Hōpoe ka lehua ki‘eki‘e i luna," from the "lehua there" to "Hōpoe, the exalted lehua on high." Hōpoe is both the name of Hi‘iaka’s close companion and a word descriptive of a fully developed, perfectly shaped lehua blossom. What ought to be an image of unclouded beauty and affection, is undermined, however, by the fact that—deal or no—Hiʻiaka worries constantly about the well-being of her friend. Consequently, the next two lines of the mele devolve into trepidation and irony. Hōpoe, we learn, is "maka‘u i ke kanaka / Lilo a i lalo e hele ai"—fearful of men because they will overwhelm her and pull her down into the lower, less-godly realm of human interaction. She is afraid of being "plucked," of being lost to Hi‘iaka. The irony of this passage derives from Hi‘iaka’s unspoken but more accurate perspective: Hōpoe is very much in danger, but the most dire threat comes from Pele, not from kānaka.

The final verse of Lōkālia’s "No Luna" is sound-dominated. We shift from far-seeing to far-listening, from "nānā ka maka" to "ho‘olono." What we listen to is "ke kai o Puna"—the sea of Puna as it rumbles over the pebble-beaches of Kea‘au and echoes in the famed hala groves of lower Puna. The nehe [15] of ‘iliʻili and the muted kuwā [16] of surf filtered through hala leaves are usually positive, kūlāiwi-defining sounds; they appear regularly in poetry, proverb, and epithet for the Puna district of Hawai‘i Island, and they are regularly associated with the rugged beauty of that coastline. "No Luna" ends, however, with the twice-repeated phrase "kai ko‘o Puna – the rough seas of Puna / surf-ravaged Puna." The phrase lends an ominous undercurrent to the normally pleasant associations of ‘ili‘ili and ulu hala. "Kai ko‘o," in Hawaiian proverb and poetry, warns of distant trouble: "‘Ano kaiko‘o lalo o Kealahula . . . There is a disturbance over there, and we are noticing signs of it here" [17]. It triggers connotations of danger and doubt: "Kaiko‘o ke awa, popo‘i ka nalu . . . A stormy circumstance with uncertain results" [18]. And it serves as a metaphor of volcanic eruption: "Popo‘i, haki kaiko‘o ka lua / Haki ku haki kakala, ka ino"; "Kai-ko‘o ka lua, kahuli ko‘o ka lani" [19]. In the context of "kai ko‘o," the rustle of ‘iliʻili becomes the rumble of storm-tossed pebbles, and the sighing of the hala groves becomes a portent of hala—of transgression, loss and death.

We know Hi‘iaka’s story; we know that everything hinted at in "kai ko‘o Puna" will soon come to pass. Moananui will not look kindly on her; a difficult channel-crossing to O‘ahu lies immediately ahead; the difficult journey will be made more difficult by Pele’s impatience and Hi‘iaka’s own growing (but dutifully repressed) interest in Lohi‘au. Promises will be broken and kūleana transgressed; waves of lava will engulf both Hōpoe and Lohiʻau, and peace will return to Puna only after Hi‘iaka’s own kai ko‘o of rage and despair has brought her sister’s world to the brink of ruin. The Hi‘iaka who gives voice to "No Luna" may not know this yet; her far-sight may not reach forward in time, but her mele offers an extraordinarily accurate assessment of the path that lies ahead. Hi‘iaka, despite her youth and inexperience, is no innocent abroad, no one-dimensional wonder-girl. Despite the foreboding view from Kahalekai and Kama‘alewa, she makes hard, loyal, keep-her-word choices right through to the end of her journey. "No Luna" allows us to appreciate the depth of Hi‘iaka’s intelligence, compassion, and character; it allows us to understand what Hawaiians valued in their most beloved heroines. Small wonder that she is still, today, a guardian-goddess of the hard-choice world of traditional hula.

We know, from first-hand experience, that "No Luna" is one of the most frequently danced and consistently misinterpreted of our legacy of carefully transmitted, pre-contact hula. Hālau Mōhala ‘Ilima’s first performance of "No Luna" occurred at the 1978 King Kamehameha Traditional Hula and Chant Competition at the Kapi‘olani Park Bandstand. We re-choreographed the dance with the idea of making it more powerful, more dramatic, and we submitted Emerson’s "fire ravaged" gloss of "Kua Loloa Kea‘au" as our explanation of "No Luna’s" hidden meaning.

We discovered our "Kua Loloa" blunder several months later when reviewing the "Hula Ala‘a-Papa" chapter of Unwritten Literature. Pi‘i ka ‘ula a hanini i kumu pepeiao! Our red-eared embarrassment over having presented, with such commitment and fervor, a kaona that didn’t even belong to "No Luna" has since made careful researchers of us—no more hasty readings of Nathaniel B., no more Mr. and Mrs. Ka‘aikiola [20]. That embarrassment was also the first in a series of lessons that helped to nudge us, a little at a time, back to the long, less-traveled path of traditional hula. We stubbornly presented the same, re-choreographed "No Luna" at the 1979 Merrie Monarch Festival, but that was the last time we presumed to improve upon the hula of our teacher’s teachers. Tsa! By 1984 we had begun, instead, to express the following definition of a kūleana to which we still adhere:

I am learning to hold true to the spirit of what my teacher gave me. I think, now that this spirit comes in two parts. First, it is my duty to respect and preserve the traditional dances. If I inherit a holokū from my grandmother, I don’t chop it up into a mini-skirt just because fashions have changed. The same hold true for the chants and hula that have been given to me. They are priceless gifts; I shouldn’t be so presumptuous as to fiddle with them just to keep up with what is fashionable. Secondly, it is also my duty to create. I am a keeper of the record of my own time and of my own place . . . [21].

No Luna i ka Hale Kai no ka Ma‘alewa

As taught by Maiki Aiu Lake to her Papa ‘Ūniki ‘Ilima, the class in which Māpuana de Silva graduated as kumu hula. Translation: Kīhei de Silva. Maiki’s "No luna" can be heard on Maiki, Hula Records, CDHS-588.

No luna i ka hale kai no ka ma‘alewa

Nānā ka maka iā Moananuikalehua

Noho i ke kai o Maliu ē

I kū a‘ela ka lehua i laila lae

‘Eā lā, ‘eā lā, ‘eā, i laila ho‘i

I laila ho‘i

Hōpoe ka lehua ki‘eki‘e i luna lā

Maka‘u ka lehua a i ke kanaka lae

Lilo a i lalo e hele ai

‘Eā lā, ‘eā lā, ‘eā, i lalo ho‘i

I lalo ho‘i

Kea‘au ‘ili‘ili nehe i ke kai lā

Ho‘olono i ke kai a‘o Puna lā ‘eā

A‘o Puna i ka ulu hala lā

‘Eā lā, ‘eā lā, ‘eā, kai ko‘o Puna

Kai ko‘o Puna

From above at Kahalekai, from Kama‘alewa

The eyes gaze at Moananuikalehua

Who resides on the shore of Maliu

With the lehua standing tall there

There, indeed

There, indeed

Hōpoe is the exalted lehua on high

The lehua is fearful of men

Leaving them to walk down below

Down below, indeed

Down below, indeed

The pebbles of Kea‘au clatter in the tide

Listen to the sea of Puna

Of Puna in the hala groves

The rough sea of Puna

The rough sea of Puna.

Sources:

Notes:

© Kīhei de Silva, 2005

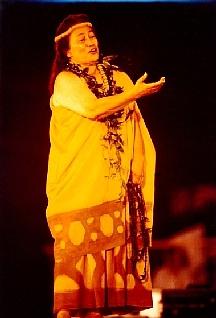

photo credit: Joe Carini

Aunty Lani (Nana) Kalama was a keeper of Lōkālia Montgomery’s version of "No Luna." According to Māpuana de Silva, "Aunty Nana always picked it when she wanted me to dance; Aunty would chant and I would dance. Because ‘No Luna’ was a favorite of hers, I danced it regularly in the ’80s and ’90s—right up until her death in January 2000. As a result, I’m very sure of the dance. Aunty didn’t let me put it aside." We know that Maiki and Nana both learned "No Luna" from Lōkālia as part of their 1946 ‘ūniki repertoire, but we don’t know who taught it to Lōkālia.