Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kīhei and Māpuana de Silva

Haku mele: Unknown.

Date: c. 1881.

Sources: 1) HI.M. 49:99, Bishop Museum Archives. 2) Puakea Nogelmeier (ed.), He Lei no ‘Emalani, 116.

Text below: Nogelmeier, 116.

E ho‘i ka nani i Mānā

I laila nā lede huapala

Kahi i ho‘ola‘i mai ai

E ō Queen ‘Emalani

Kaleleonālani he inoa.

E aha ana lā ‘Emalani

I ka wai kapu a Lilinoe

E nanea, e walea a‘e ana

I ka hone mai a ka palila

Ke kō mai nei ke ‘ala

Kūlia hau anu o ka uka

I ka ‘olu la‘i o ka māmane

Kolonahe mai ana e ke anu

I ka uka ‘iu‘iu o Waiau

Ho‘olale mai ana Lilinoe

Ka wahine noho i ke kuahiwi

E huli e ho‘i kākou

E ō Queen ‘Emalani

Kaleleonālani he inoa.

May the beauty return to Mānā

The beautiful ladies are there

Where they have found contentment

Respond, O Queen Emmalani

For Kaleleonālani a name song

What is Emmalani doing there

At the sacred water of Lilinoe?

She is relaxing and she is enjoying

The soothing song of the palila bird

A fragrance is being carried on the wind

The cold chill of the highlands is stilled

At the serene calm of the māmane trees

Gently buffeted by the cold

At the lofty heights of Lake Waiau

Lilinoe is offering encouragement [1]

The woman who dwells on the mountain

Let us turn and be on our way [2]

Respond, O Queen Emmalani

For Kaleleonālani a name song.

Queen Emma visited Maunakea in the early 1880s—probably in 1881. Her journey began in Mānā, Waimea, on the north side of the mountain, and she traveled by horseback along its western flank to Pu‘u Kala‘i‘ehā on the tableland to the south. Her party included her own po‘e kau lio and two guides: William Seymour Lindsey of Waimea and Waiaulima of Kawaihae. The travelers spent the night at the Kala‘i‘ehā Sheep Station, the only permanent shelter in thirty miles [3], and they rode, the next morning, to the summit of Maunakea. After the six-hour climb [4], Emma took in the view from the heights of Kūkahau‘ula [5] and swam in Lake Waiau. The tireless queen then turned, urged her saddle-weary companions to "‘eleu mai ‘oukou," and began the long journey home.

We know of eight mele that commemorate Emma’s ascent of Maunakea, and we are familiar with a narrative of her trip as given by Mrs. Mary Kalani Ka‘apuni Phillips, a descendant of William Seymour Lindsey. The eight mele are summarized below in what we think is their correct, from-Mānā-and-back, geographical order. Until a few years ago, these mele were available only in the manuscript collections of the Bishop Museum Archives, and they have never been assembled in this larger context of what we call Emma’s "Mele Pi‘i Maunakea." Puakea Nogelmeier, however, has begun to remedy this oversight with his 2001 publication of He Lei no ‘Emalani, a compilation of chants for Queen Emma in which he catalogs seven of our mele as māka‘ika‘i (travel) and the eighth as kālai‘āina (political). Nogelmeier makes the point, in the Mele Māka‘ika‘i section of his book, that Emma’s "intrepid nature led her to investigate the summits [of Wai‘ale‘ale and] other mountains, including . . . a particularly rigorous ride up Maunakea to see the wonders of Waiau" [6], but he neither organizes nor annotates the Maunakea chants in the following manner. This, then, is our own taxonomy and interpretation of the heretofore fragmented collection.

• "E Ho‘i ka Nani i Mānā" – this 19-line composition encompasses the entire trip and anticipates Emma’s empowered return to Mānā from the glorious māmane groves of the tableland and the majesty of Waiau (Nogelmeier, 116).

• "Kaulana ke Anu i Waiki‘i" – this 22-line composition describes the ascent from Waiki‘i to the Maunakea summit and back to Kala‘i‘ehā; it extols Emma’s leadership and adorns her in māmane and birdsong (N, 120).

• "Eia ka Makana e Kalani Lā" – this 16-line composition describes the panoramic assembly of mountains (Maunakea, Maunaloa, and Hualālai) visible on the approach to Kala‘i‘ehā. Nature anoints and adorns the queen; she is clearly suited for high places and meant to rule once more (N, 113).

• "Hau Kakahiaka Nui ‘o Kalani" – this 20-line composition follows Emma from Kala‘i‘ehā to Lake Waiau; it extols her leadership and recounts her great desire to experience Waiau, the navel of Wākea (N, 112).

• "Kō Leo ka Ma‘alewa" – this 25-line composition describes Emma’s view of Waimea, Kawaihae, and Kailua from the Maunakea summit; it characterizes the experience as the ultimate in spiritual rejuvenation (N, 109).

• "Kūwahine Hā Kou Inoa" – the 16-line tenth verse of this 14-verse, 196-line composition describes an upwelling of water at Waiau and a blooming of māmane and lehua on the slopes below. Thus does Mauna Wākea endorse Emma’s high rank and renewed capacity for leadership (N, 180–181).

• "E Aha ‘ia ana Maunakea" – this 18-line composition looks south from Maunakea’s misty summit; its compass includes Maunaloa, Kīlauea, Halema‘uma‘u, and the murmuring sea of Puna. The same is true of Emma’s influence and appeal (N, 114).

• "A Maunakea ‘o Kalani" – this 14-line composition begins with Emma’s rejuvenation at Waiau and describes her energy and leadership on what, for her companions, is a very long ride home (N, 115).

Because each of these mele is composed from a different geographic perspective, a side-by-side comparison of all eight allows us to reconstruct the view-plane and place-name sequence of the trip: Emma journeys from Mānā to Kemole, from Kemole to Kala‘i‘ehā in a broad curve bordered by Waiki‘i and Ahumoa; from Kala‘i‘ehā to the Kūkahau‘ula summit by way of Pu‘u Ho‘okomo and Pu‘u Kilohana; from the vistas of Poli‘ahu and Lilinoe to the waters of Waiau; and from Lake Waiau all the way back to Kemole, Wahinekea, and Mānā.

The same side-by-side comparison allows us to recognize the carefully orchestrated language of these compositions—the shared imagery of adornment, anointment, height, and reach; the recurring metaphors of spiritual reconnection, rebirth, and rejuvenation; and the repeated references to Emma’s energy and leadership. These mele are remarkably interconnected. Each can be seen as a paukū in a coherent, eight-part whole whose underlying figurative meaning is that of empowerment. Emma is empowered by the success of her trip; Mauna Wākea, the father-mountain [7], sanctions her right and capacity to rule the nation. Emma had lost the 1874 election to Kalākaua, but neither she nor her people had given up hope, political activism, or poetic discourse [8]. When Kalākaua embarked on his world tour in January 1881, Emma countered with this journey to the top of the world, to Maunakea [9]. When Kalākaua sought recognition in foreign lands, Emma gained the approval of Wākea himself; she experienced firsthand the sacred piko at which father and mother, sky and land, conjoin.

The eight Maunakea chants, when considered side by side, give us geography and kaona. They tell us, "This is where Emma went." And they tell us, "This is the hidden meaning of that journey." Mary Kalani Ka‘apuni Phillips’s account, on the other hand, supplies us with the details of character and episode with which we can populate the geography of the chants and ground their figurative language in actual events and emotions. Phillips, a descendant of Emma’s guide William Seymour Lindsey, was born in 1902 in Anahulu, Kona, Hawai‘i. She was interviewed by Larry Kimura—another descendant of W. S. Lindsey—in 1967, and she relates the story of Emma’s pi‘i mauna as part of a longer talk-story session that is accessible, on tape, in the audio collection of the Bishop Museum Archives [10].

It is Phillips who identifies the elder Lindsey as the pailaka of Emma’s expedition, Phillips who explains that Waiaulima was one of Emma’s kaukau ali‘i who had come up from Kawaihae, and Phillips who describes the skill and enthusiasm of Emma and her po‘e kau lio: "Ma ka lio. Kau lio. ‘O Queen ‘Ema he wahine kau lio kēlā! A ‘o kona po‘e kau lio, po‘e hoihoi lio wale no!" (They went to Maunakea on horses. On horseback. Queen Emma—now there was a horsewoman! As for her horse-riding retainers, they were people who were obsessed with horses!)

Phillips also relates the story of Emma’s swim at Waiau: "Kau ‘o Queen ‘Ema i luna o ke kua o Waiaulima . . . a ‘au ‘o ia a puni i kēia pūnāwai ‘o Waiau, no Maunakea. A hāpai ‘o ia iā Queen ‘Ema, a ka‘i ‘o ia . . . i kahi wahi pōhaku. Pu‘iwa ho‘i ka po‘e e ‘ike ana i kēia ‘au ma luna a Queen ‘Ema . . . a ho‘i mai lākou a ha‘i mai i ka mo‘olelo iā mākou." (Queen Emma rode on the back of Waiaulima, and he swam around Waiau pond at Maunakea. And then he lifted Queen Emma and carried her to a rocky place. The people were amazed to see Queen Emma’s on-the-back swim, and they returned and told the mo‘olelo to us.) Phillip’s account is especially important to us because this "‘au ma luna a ‘Ema" is barely evident, at best, in the eight chants composed for the Queen’s ascent. Three of Emma’s mele omit the Waiau swim entirely. The other five refer to the event with so much poetic indirection that, without Phillips, we can’t really identify it as an actual in-the-water experience.

The first of these Waiau mele, "E Ho‘i ka Nani i Mānā," devotes two ambiguous couplets to a possible swim; it asks, "E aha ana lā ‘Emalani / I ka wai kapu a Lilinoe?" and answers, "E nanea, e walea a‘e ana / I ka hone mai a ka palila." (What is Emma doing / At the sacred water of Lilinoe? / She is relaxing and enjoying / The sweet song of the palila.) The second Waiau mele, "Hau Kakahiaka Nui ‘o Kalani," refers to Emma’s experience with equal ambiguity: her great desire is to "‘ike maka iā Waiau / Kau pono i ka piko o Wākea" (to ‘know’ Waiau firsthand / There at the navel of Wākea). The third mele, "Kūwahine Hā Kou Inoa," says nothing of the swim itself; it hints that the lake, for Emma, is "ka piko lālāwai o nā mana‘o" (the fertile center of thought and desire), and it suggests, in highly figurative language, that the effect of her not-mentioned swim is an upwelling of "ka wai māpuna o ke kuahiwi / I hū nō a piha i luna o Poli‘ahu" (the upwelling mountain water / That rises to fill the summit of Poli‘ahu). The fourth mele, "E Aha ‘ia ana Maunakea," alludes to Emma’s swim as "ka hā‘ale a ka wai hu‘i a ka manu" (the rippling of the chilly water of the birds). And the last mele, "A Maunakea ‘o Kalani," describes the experience in the same round-about, "‘ike maka" language with which we are now quite familiar: "‘Ike maka iā Waiau / Kēlā wai kamaha‘o / I ka piko o ke kuahiwi" (She "sees" Waiau with her own eyes / That amazing lake / At the peak of the mountain).

Without Phillips’s mo‘olelo, we float in the figurative. Does Emma see, know, experience, or actually immerse herself in Waiau? With Phillips’s help, we can anchor this veiled, highly evasive language to Emma’s swim in the lake, and we can appreciate, as well, the deliberately ambiguous, kaona-creating techniques of Emma’s poets. They ‘au‘a. They withhold the specific details of the defining event of their queen’s journey and cloak the experience, instead, in mystery and majesty.

A second episode in Phillips’s narrative allows us to identify, in similar fashion, the source of the anoint-and-adorn references that are central to four of the mele pi‘i Maunakea. Phillips explains that Emma’s party was detained, on the first leg of the trip, by a rainstorm at Kahalelā‘au—an area north and ma uka of Waiki‘i in what is now the Pu‘u Lā‘au Dry-Forest Reserve: "Lawe lākou i . . . Kahalelā‘au, ‘o ia ka inoa o ia wahi. ‘A‘ohe wahi—nui ka ua, hu‘i i ka ua—‘a‘ohe wahi e malu ai. No laila kēia po‘e kānaka me [Lindsey], ha‘iha‘i lākou i ka lā‘au māmane. Hana lākou i hale no Queen ‘Ema." (They took Emma to Kahalelā‘au, that was the name of this place. There was nowhere—the rain was heavy, they were chilled by the rain—there was nowhere for them to take shelter. So these people with Lindsey, they broke off māmane branches. They made a house for Queen Emma.)

Isabella Bird traveled the same Mānā-Kemole-Kala‘i‘ehā-Waiau trail in 1875. She describes the Lā‘au tableland as "the loneliest, saddest, dreariest expanse I ever saw . . . nothing softened into beauty this formless desert of volcanic sand, stone, and lava, on which tufts and grass and a harsh scrub war with wind and drought for a loveless existence . . . [it is] always the same rigid māmane, the same withered grass, and the same thornless thistles, through which the strong wind swept with a desolate screech" [11].

Emma’s party and poets, however, viewed Lā‘au with completely different eyes. The mele "E Ho‘i ka Nani i Mānā" depicts the event as one of fragrant serenity: "Ke kō mai nei ke ‘ala / Kūlia hau anu o ka uka / I ka ‘olu la‘i a ka māmane" (A fragrance carries here / The cold chill of the uplands is stilled / By the serene comfort of the māmane trees). The mele "Kaulana ke Anu i Waiki‘i" describes the invigorating nature of this rainy interlude: Emma pauses to enjoy the famous cold of Waiki‘i, the chill of which was "‘olu i ka ‘ili o Kalani" (pleasant on the skin of the royal one); she delights in "ka leo hone a ka palila" (the sweet voice of the palila); and when she takes up the journey again, "ua wehi [‘ia ‘o ia] i ka pua māmane" (she was adorned in māmane blossoms). The mele "Eia ka Makana e Kalani" tells us that the Queen is welcomed at Lā‘au by a gift of rain that moistened her cheeks with "ka wai kēhau i ka liko māmane" (the dewy water that graces the new māmane shoots). And the mele "Kūwahine Hā Kou Inoa" again describes Emma in the context of her māmane adornment: when the storm passes, "Ua ‘ehu wale i ka lā ka pua māmane / Ua kupali‘i wale i ke kēhau anu o uka" (Pure gold in the sun are the māmane flowers / Stunted and dwarfed by the cold dew of the highlands).

Isabella Bird saw a wasteland. A rainstorm, we suspect, would have compounded her discomfort and bleak perspective. Emma’s people, however, saw the squall as an opportunity to demonstrate their resourcefulness and aloha. Their hale lau māmane, their temporary shelter of māmane leaves, allowed for increased proximity to the Queen and added to the intimacy of their shared experience. The rainstorm tied them to the land, to Emma, and to each other; they saw it, therefore, as a profound experience. They took it as a blessing.

Mary Phillips notes that one long-lasting consequence of this blessing was Emma’s gift of a name to a future child of William Seymour Lindsey: Emma told him, "I noho ‘oe a hānau kāu wahine, kapa iho ‘oe i ka inoa ‘o Kahalelau-māmane" (When you join with your wife and she gives birth, name the child Kahalelaumāmane). Lindsey didn’t forget. His son William Kahalelaumāmane Lindsey was born in 1882 [12], and the name—according to Larry Lindsey Kimura—has been passed on to more recent members of the Lindsey family [13]. The name serves as a trans-generational tie; it evokes a history, a roll call of po‘e kau lio, and fond memories of a golden past. The name also provides us with a solid upper-limit for the date of Emma’s trip. Various sources identify this date as c. 1881 [14] and 1883 [15]. Kahalelaumāmane’s 1882 birthday, rules out the last of these and makes an 1881 expedition date all the more likely.

If Emma’s people transformed the Lā‘au downpour into a blessing; the poets among them went even further. They withheld the specifics of storm and shelter and parlayed the rainy interlude into a subtle metaphor of anointment and coronation. In their four mele māmane, nature pauses to confirm Emma’s status as the once and future queen. She is bathed in fragrance, sanctified with dewy water, heralded with birdsong, and crowned with glowing blossoms. These mele suggest that Emma’s ascent of Maunakea is symbolic of a much-hoped-for, even more important ascent: her return to the throne. Her poets adorn her here, at Kahalelā‘au, for that highest office.

The historical record of pilgrimages to Maunakea is not limited to Emma’s mele and Phillips’s mo‘olelo. Steven Desha writes that, as a young man, Kamehameha Pai‘ea went to Waiau to pray and leave an offering of ‘awa [16]. Kamakau tells us that Ka‘ahumanu made the same journey in 1828 in an unsuccessful attempt to retrieve the iwi of her ancestress Lilinoe [17]. Kauikeaouli visited Waiau and the summit in 1830 [18], Alexander Liholiho in 1849 [19], and Peter Young Ka‘eo in 1854 [20]. According to Kepā Maly, stories of trips to the mountain and knowledge of its traditional significance are still maintained in Hawaiian families of the late 20th century. His informants have told him of travel to the summit region to worship, purify themselves, and reconnect with their ancestors, to collect healing water from Waiau, to procure stones for adz-making, to deposit the piko of their newborn, and to release the ashes of their deceased [21].

The words of two of these informants testify to the remarkable consistency with which the mountain has been regarded across the generations that separate the 19th century Queen Emma, for example, from the 20th century construction worker Lloyd Case. Irene Fergerstrom—a descendant of William S. Lindsey—told Maly that Emma ascended Maunakea and swam across Waiau on a quest for "physical and spiritual well-being" [22]. Lloyd Case—born in Waimea in 1949—explained to Maly that he goes to the summit for the physical and spiritual renewal: "[It] is the most rewarding thing that I can ever say happens to me. When I go up there, it just heals me. That is a place for healing. I come back a different person" [23]. The Queen and Case were born 113 years apart, but their regard for Mauna Wākea is identical.

What separates the Emma’s chants and Phillips’s narrative from these valuable and highly corroborative accounts is weight and focus. Eight mele pi‘i Maunakea and a 300-word story pack more punch than a Kamakau sentence here and Ka‘eo letter there. The pū‘olo ‘ōlelo (word package) of Emma’s trip constitutes a powerful legacy: the history of a single visit to Maunakea as told by Hawaiians in two very Hawaiian formats. This pū‘olo schools us in the properties of mo‘olelo and mele; it reveals the points at which the two meet, the points at which they diverge, and the manner in which each was meant to inform the other. This pū‘olo also provides us with an understanding of the process by which late 19th century Hawaiians transformed event into poetry: how they narrowed and fragmented their focus, withheld important narrative details, emphasized peripherals, and embedded figurative meaning in proper names, nature, natural phenomena, and geographic alignments. Finally, Emma’s pū‘olo allows us to appreciate the mindset of her people when their mo‘olelo and mele were first shared with the larger community. Her hoa kau lio knew the back-story firsthand; they could track both the literal and the figurative. They could delight in what was withheld, emphasized, revealed, and transformed. They could explain or keep silent. Emma’s pū‘olo provides us with a little of this insider’s perspective, something that has been unavailable to most of us for several generations.

Our insider’s perspective is further enhanced by a legacy of dance. One of Emma’s eight mele pi‘i Maunakea—"A Maunakea ‘o Kalani"—has survived the intervening century as a hula ‘ili‘ili in the repertoire of Mary Kawena Pukui, the granddaughter of one of Emma’s court dancers and the niece of another [24]. We learned "A Maunakea ‘o Kalani" from Aunty Pat Namaka Bacon, Kawena’s daughter, in June 1985. In the intervening twenty years, we’ve slowly, erratically, and often accidentally pieced together its meaning and context, and we’ve only recently come to appreciate its significance as a treasure of voice and motion from that 1881 expedition.

We perform "A Maunakea ‘o Kalani"—the last chant in the mele pi‘i Maunakea sequence—as the main hula in our Merrie Monarch kahiko set. We introduce it with a chanted-only version of "E Ho‘i ka Nani i Mānā"—the first mele in this same sequence. We think that "E Ho‘i ka Nani" serves as a particularly appropriate introduction to "A Maunakea ‘o Kalani" because it alone addresses the entire trip from Mānā to Maunakea and back, and because it best encompasses the themes of immersion, anointment, adornment, and empowerment that are developed in more isolated fashion in of each its seven sister mele. More specifically, "E Ho‘i ka Nani i Mānā":

• defines the scene at Mānā as one of up-country elegance in which "nā lede huapala" (beautiful, desirable ladies) wait, in poised "ho‘ola‘i" fashion, for the travelers’ return

• implies that Emma has found spiritual and physical rejuvenation "i ka wai kapu a Lilinoe . . . i ka uka ‘iu‘iu o Waiau" (in the sacred water of Lilinoe at the lofty heights of Lake Waiau); anoints Emma with wind-borne fragrance "i ka ‘olu la‘i a ka māmane" (in the serene calm of the māmane); and further establishes Lilinoe as "[ka mea e] ho‘olale mai ana"—the ancestral deity who encourages/empowers Emma when the queen leaves Waiau for the world below.

"E Ho‘i ka Nani i Mānā" comes to a close, in fact, at the focal point of "A Maunakea ‘o Kalani"—at the point in the journey when the newly immersed and energized queen encourages her people to "huli ho‘i" and to "‘eleu mai." The eighth mele in the sequence thus takes up where the first leaves off; the two are more than bookends for Emma’s mele pi‘i Maunakea; they speak to each other; they dovetail.

The voice for this oli is, of course, our own. Unlike "A Maunakea ‘o Kalani," "E Ho‘i ka Nani" has survived only as a handwritten text on a manuscript page. We feel, however, that ours is an informed voice, one that calls sweetly back over the generations with the message: ‘a‘ole mākou i poina wale i nā lede huapala o Mānā; e ō Kohala i ka huapala kau i ka nuku; e ō Kuini Emalani, Keali‘ipi‘imauna he inoa. We haven’t forgotten the beautiful ladies of Mānā; respond, O Kohala, whose people delight our eyes and fill our mouths with stories; respond, Queen Emma; for The-chiefess-who-ascends-mountains we offer this name song.

Notes:

1. Puakea Nogelmeier translates this line as "Lilinoe is beckoning." We think, however, that ho‘olale is best interpreted as "encourage, urge, incite." Emma has immersed herself in the sacred waters of Lilinoe and has emerged with new energy and purpose. Lilinoe can be seen, then, as encouraging the Queen to hurry home and take up the task of leading her people.

2. Nogelmeier translates this line as "Let us turn and go back." Although this is an accurate, literal rendering of "e huli e ho‘i kākou," it seems to invite unnecessary ambiguity to the verse. Are we turning and going back to Mānā, or are we turning and going back to Lilinoe’s mountain home? "Let us turn and be on our way," though not quite literal, makes it clear that the travelers are returning to Mānā with Lilinoe’s blessing. With the exception of these two lines—"Ho‘olale . . ." and "E huli . . ."—the translation above is all-Nogelmeier and all accomplished with considerable elegance.

3. The Kala‘i‘ehā Sheep Station is on the current Maunakea Observatory Access Road. It was established informally in 1856 to capitalize on the wool market afforded by feral sheep already in the area. Kamehameha IV leased the station in about 1860 to the Waimea Grazing and Agriculture Co. (NASA Burial Treatment Plan for the Outrigger Telescopes Project, Appendix C:14–15, July 21, 2004). Isabella Bird, who rode by horseback from Mānā to Waiau in May 1875, described the station as consisting of a shed, several grass huts, a tent, and a rude cabin. She numbered the domesticated sheep population at 9000 and identified the nearest residence as the Hualālai station, "thirty miles off." (Isabella Bird, The Hawaiian Archipelago . . ., Letter XXV.)

4. The duration of Emma’s ride is not recorded. Isabella Bird, however, describes the same climb as taking six hours of steady, strenuous riding (Ibid). Because Bird made this ascent under ideal weather conditions, we are assuming that Emma could not have done it any faster.

5. The three peaks at the summit of Maunakea now bear the names Pu‘u Kea, Pu‘u Wēkiu (the highest peak), and Pu‘u Hau‘oki. Kūkahau‘ula, however, is the older name for the summit peak and cluster (Kepā Maly, Mauna Kea – Kuahiwi Kū Ha‘o Mālie, 11). The poets of Emma’s Maunakea trip refer to the summit as Piko o Wākea (Puakea Nogelmeier, He Lei no ‘Emalani, 112) and Kūkahau‘ula (Nogelmeier, 180).

6. Puakea Nogelmeier, He Lei no ‘Emalani, 66.

7. Although Maunakea is popularly translated as "white mountain," Kea is also an abbreviated form of Wākea, the sky father who, with Papa, the earth mother, stands at the apex of Hawaiian genealogy. Mauna Wākea is thus viewed traditionally as the sacred meeting point of sky and earth, father and mother, Wākea and Papa. Emma’s poets were well-acquainted with the older name and its lasting significance; they refer to Waiau as "ka piko o Wākea"—as the mountain’s navel/genital/umbilical/connecting-point/center.

8. Many of Emma’s staunchest supporters, in fact, came from North Kona, Kohala, and Waimea; they voted George Washington Pilipo, an "Emmaite," to the legislatures of 1876-1884 (George Kanahele, Emma, Hawai‘i’s Remarkable Queen, 311, 347, 361. "Nasty genealogical fighting" over Kalākaua’s victory continued well into 1883 when Emma refused to attend Kalākaua’s coronation because, her people argued, he was not "of sufficient ali‘i lineage" to rule the nation (Ibid, 357).

9. "[Kalākaua and Emma] embarked on journeys to prove their connection to the senior line . . . Emma went to the top of Maunakea to bathe in the waters of Waiau and cleanse herself in the piko of the island." Edward and Pualani Kanahele, Hawaiian Cultural Impact Assessment of the Proposed Saddle Road Alignments, 1992. The Kanaheles do not discuss Kalākaua’s world tour, that reference is our own.

10. Mary Kalani Ka‘apuni Phillips, interviewed by Larry Lindsey Kimura, 1967; Bishop Museum Archives Audio Collection, 192.2.2, Side A. The interview was conducted entirely in Hawaiian; all translations provided here are our own.

11. Bird, Letter XXV. Bird’s letters can be viewed online at etext.library.adleaide.edu.au./b/bird/ isabella/hawaii.index.html.

12. Kahalelaumāmane Lindsey’s 1882 birth date is recorded by Kepa Maly in his Mauna Kea Science Reserve and Hale Pōhaku Complex Plan Update . . ., 1999. A list of his interviewees and their backgrounds is available online at envirowatch.org.MKoverview.htm.

13. Maly, 1999.

14. Irene Lindsey-Fergerstrom, interviewed by Kepa Maly, 1999. Also in Edward and Pualani Kanahele, 1992.

15. W.D. Alexander, "The Ascent of Mauna Kea Hawaii," Hawaiian Gazette, September 30, 1892; cited in Burial Treatment Plan for the Outrigger Telescopes Project . . ., NASA, 2004, p. C–3. Also in a note attached to "Eia ka Makana e Kalani," fHI.M. 50:140, Bishop Museum Archives.

16. Steven L. Desha, Kamehameha and His Warrior Kekūhaupi‘o, 93–94.

17. Samuel M. Kamakau, Ke Aupuni Mō‘ī, 46.

18. NASA, 2004, c–3.

19. Alfons Korn, Our Victorian Visitors, 217.

20. Letter from Peter to Emma in Korn, News from Moloka‘i, xvi.

21. Maly, 1999; cited in Mauna Kea Scientific Reserve Master Plan, v–8–9, 17–19.

22. Maly, 1999; envirowatch.org/MKoverview.htm, p. 9. Fergerstrom was born in Waimea in 1932.

23. Maly, 1999, a–353; MKSRMP, v–17.

24. Nali‘ipo‘aimoku and Joseph ‘Īlālā‘ole. According to Patience Namaka Bacon, "Po‘ai" went traveling with Emma whenever the Queen called. ‘Īlālā‘ole lived in Honolulu with Emma, and Emma, in turn, stayed at "Uncle ‘Ī’s" grandfather’s house in Kaimū whenever she visited Puna and Ka‘ū.

© Kīhei and Māpuana de Silva 2006

The essay above was written by Kīhei and Māpuana de Silva and excerpted from their 2006 Hālau Mōhala ‘Ilima Merrie Monarch Fact Sheet. It is offered here, in slightly revised and updated form, with their express consent. They retain all rights to this essay; no part of it may be used or reproduced without their written permission.

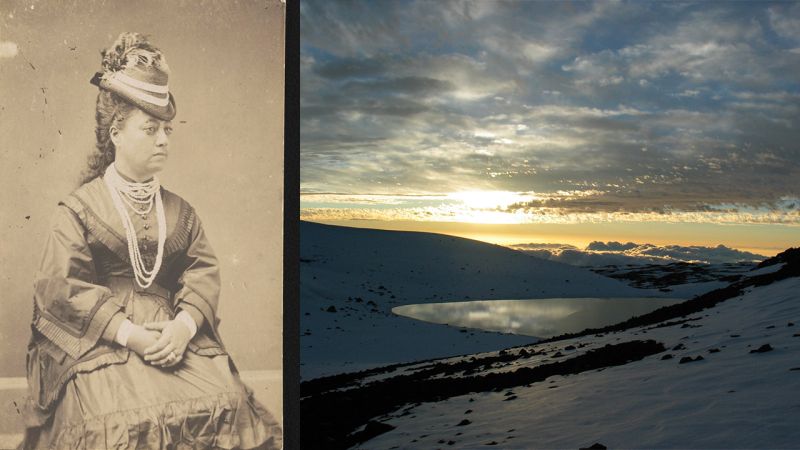

photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

I ka uka ʻiuʻiu o Waiau – At the lofty heights of Lake Waiau.

photo credit: U.S. Geological Survey

The palila, an endangered honeycreeper endemic to Hawaiʻi, inhabits the māmane forests on the slopes of Maunakea.

photo courtesy of: Library of Congress

"Kau ‘o Queen ‘Ema i luna o ke kua o Waiaulima . . . a ‘au ‘o ia a puni i kēia pūnāwai ‘o Waiau, no Maunakea. A hāpai ‘o ia iā Queen ‘Ema, a ka‘i ‘o ia . . . i kahi wahi pōhaku. Pu‘iwa ho‘i ka po‘e e ‘ike ana i kēia ‘au ma luna a Queen ‘Ema . . . a ho‘i mai lākou a ha‘i mai i ka mo‘olelo iā mākou." (Queen Emma rode on the back of Waiaulima, and he swam around Waiau pond at Maunakea. And then he lifted Queen Emma and carried her to a rocky place. The people were amazed to see Queen Emma’s on-the-back swim, and they returned and told the mo‘olelo to us.)