Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kīhei de Silva

Haku mele: Unknown. This mele inoa was composed for Kupakeʻi, a beloved chief of Kaʻū in the time of Kamehameha I.

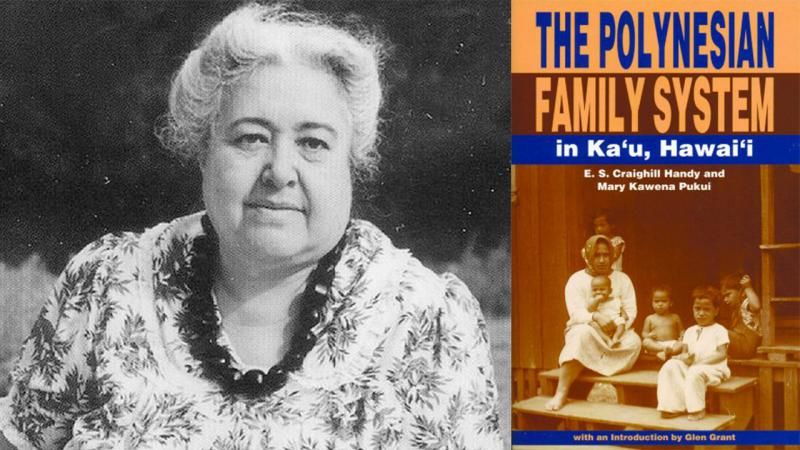

Sources: The chant book of Alice Maukaʻa Kukaʻilani Hayselden (a direct descendant of Kupakeʻi), MS. 89:183, Bishop Museum Archives. Roberts Collection, Bk 23:27–43, Bishop Museum Archives. Mary Kawena Pukui, HEN III: 952–4, Bishop Museum Archives; “Songs of Kaʻū, Hawaiʻi,” Journal of American Folklore; 251–252. Pukui and Handy, The Polynesian Family System in Kaʻū, Hawaiʻi, Japan 1972:85.

Discography: Kahaʻi Topolinski, Nou e Kawena, Pumehana Records PSC 4296. Oli performed by Anthony Lenchanko under the title “ʻO Kaʻū Kaʻu.”

Text and translation below: Pukui, Polynesian Family System, 85. Line numbers have been added for ease of reference.

1. ʻAʻole au i makemake iā Kona,

2. ʻO Kaʻū kaʻu.

3. ʻO ka wai o Ka Lae e kahe ana i ka pō a ao.

4. I ke kapa, i ka ʻūpī kekahi wai

5. Kūlia i lohe ai he ʻāina wai ʻole

6. I Mānā, i Unulau ka wai kali

7. I ka pona maka o ka iʻa ka wai aloha ē,

8. Aloha i ka wai mālama a kāne

9. E hiʻi ana ke keiki i ka hōkeo,

10. E hano ana, e kani ō uō ana,

11. Ka leo o ka hue wai i ka makani

12. Me he hano puhi ala i ke aumoe,

13. Ka hoene lua a ka ipu e ō nei.

14. E lono i kou pōmaikaʻi, Eia!

15. Mamuli o kou hope ʻole, ʻokoʻa kā hoʻi,

16. A ma ka wā kamaliʻi nei, mihi malu,

17. ʻŪ wale iho nō.

18. Aloha ʻino nō kā hoʻi ke kau ma mua.

19. ʻUʻina ʻino nō hoʻi ke kau i hala aku nei.

1. I do not care for Kona,

2. For Kaʻū is mine.

3. The water from Ka Lae is carried all night long.

4. (Wrung) from tapas and some from sponges.

5. This land is heard of as having no water,

6. Except for the water that is waited for at Mānā and Unulau.

7. The much prized water is found in the eye socket of the fish,

8. The water prized and cared for by the man

9. The child carries a gourd container in his arms.

10. It whistles, whistles as the wind blows into it,

11. The voice of the water gourd is produced by the wind

12. Sounding like a nose flute at midnight,

13. This long, drawn-out whistling of the gourd, we hear.

14. Hearken, how fortunate you are!

15. There is no going back, (our) ways are different.

16. In childhood only does one regret in secret,

17. Grieving alone.

18. (Look) forward with love for the season ahead of us.

19. Let pass the season that is gone.

“ʻAʻole Au i Makemake iā Kona” is the fifth paukū of a six-paukū, 174-line name chant entitled “He Inoa no Alakaihu Oia o Kupakei.” The oldest text of this composition is contained in a handwritten book of chants belonging to the great-granddaughter of Kupakeʻi, Mrs. Alice Maukaʻa Kukaʻilani Hayselden of Waiʻōhinu, Kaʻū. Mrs. Hayselden’s son Howard Kupakee Hayselden entrusted the book to the Bishop Museum in 1953. A nearly identical version of the chant was collected in the 1920s by Helen Roberts (Bk. 23: 27–43) and translated by Kawena Pukui, a cousin of Mrs. Hayselden’s mother (HEN III: 952–4). Tūtū Kawena published the fifth paukū of the complete chant in “Songs of Kaʻū” and The Polynesian Family System; Anthony Lenchanko performed this same section under the title “ʻO Kaʻū Kaʻu,” on Kahaʻi Topolinski’s audio cassette Nou E Kawena.

In a letter that accompanied the gift of the Hayselden chant-book to the Bishop Museum, E. C. Handy identified Kupakeʻi as “belonging to the line of the ancient High Chiefs of Kaʻu.” He was the aliʻi “who would have succeeded Keoua-kuahu-ula as High Chief of that district had Kamehameha I not conquered Kaʻu...[and] appointed as High Chief, Keawe-a-heulu” (Handy to BPBM director, August 13, 1952, HI. M.89, Bishop Museum Archives).

The John Liwai Ena genealogy published in Ke Aloha Aina, March 9, 1907, corroborates Handy’s summary of Kapakeʻi’s descent: ʻĪ (a great-grandson of ʻUmi) joined with Kūwalu, born was Ahu-a-ʻĪ (k); Ahu-a-ʻĪ joined with Piʻilaniwahine, born was Lonomaʻaikanaka (w), a chiefess of Kaʻū; Lonomaʻaikanaka joined with Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku, born was Kalaninuiʻīamamao (k), aliʻi nui of Kaʻū; Kalaninuiʻīamamao joined with Kamakaʻimoku, born was Kalaniʻōpuʻu (k), aliʻi nui of Kaʻū; Kalaniʻōpuʻu joined with Manoua of Kaʻū, born was Kūkanaloa (k) “forebearer...of the chiefs of Kaʻū, namely Kupakeʻi and Kaiahua [his daughter]. The chiefly children of Kaiahua issued forth” (collected and translated by Edith McKinzie, Hawaiian Genealogies, Honolulu 1991, II:104).

We have no date for Kupakeʻi’s birth, but we can infer that a grandson of Kalaniʻōpuʻu’s (d. 1782) who would have succeeded Keōuakūʻahuʻula (d. 1791) as aliʻi nui of Kaʻū had Keaweaheulu not usurped that position, was probably born in the 1780s. Kupakeʻi would have then been old enough to be recognized as Keōuakūʻahuʻula’s successor, but not old enough to have accompanied his uncle to the slaughter at Kawaihae. We have no date for Kupakeʻi’s death, but a reference in Kamakau’s Ruling Chiefs describes Kupakeʻi in 1815 as actively evading Kamehameha’s efforts to “meet” with him and as supporting a large following in the back-country of Kaʻū (205–206). These descriptions seem consistent with the energies of a man still in his prime, as a 30–35-year-old Kupakeʻi would certainly have been. A final set of facts and hints—1) the birth of Joseph ʻĪlālāʻole in 1873, 2) the fact that ʻĪlālāʻole was Kupakeʻi’s grandson, and 3) the mention, in two of the Bishop Museum Archives’ notes to the mele “A Luna Au o ʻĀhia,” that this mele was a name chant for Kupakeʻi and a mele composed for ʻĪlālāʻole at his birth by his grandparents—suggests to us that Kupakeʻi was still alive in 1873. Inferences aside, we can certainly say that Kupakeʻi’s life began in the late 18th century and continued long enough into the 19th for him to have become a beloved ancestor of his people and a symbol of their indomitable spirit.

The character of Kupakeʻi, and of the people who cherished him, is evident in Kawena Pukui’s notes to the Kupakeʻi name chants in the Hayselden and Roberts Collections (there are two mele inoa for Kupakeʻi: “He Inoa no Alakaihu Oia o Kupakei”—of which our oli is a part—and the equally lengthy “He Inoa no Alakaihu Kupakei”). Pukui begins by explaining that the Kaʻū people to whom Kupakeʻi belonged were called the “Mākaha” and originated from a chief and chiefess who, because of parental disapproval, eloped to the rugged coast of Kamāʻoa, Kaʻū. Their children were prolific, and these, in turn, produced a multitude of descendants. Despite the harsh environment, the resourceful family found ways to procure water, cultivate the land, and make the most of the prized fishing grounds that lay just off Ka Lae. In time, the eldest line of this vast and independent family was looked up to as the aliʻi of the district by the junior branches of the same line; all were of chiefly descent, but by common agreement, the “younger” ones made no public reference to their own rank. It became a matter of family pride to keep this status hidden from all outsiders and to maintain the integrity of the line by marrying only within the district. Thus, among themselves, the people of Kaʻū shared the saying, “Mai ka uka a ke kai, mai kahi pae a kahi pae, he ʻohana wale nō – From upland to sea, from end to end, one family only” (HEN III:938).

Pukui goes on to say that, as a result of their common lineage, the people of Kaʻū loved their aliʻi with a fierce and possessive intensity. "Their own aliʻi meant more to them than any others and though they received and entertained visitors they never encouraged them to stay among them" (Ibid.). Pukui offers an example of the severity with which the Mākaha treated the family chiefs who dared to break their bonds of reciprocal allegiance: the chief Halaʻea fell into the habit of cheating his fisherman of their catch; instead of distributing the fish fairly, he took everything for himself and his favorites. Consequently, the angry fishermen lured him out to sea, piled his canoe with so many fish that it sank, and left the chief to drown. Pukui also offers an example of the passionate loyalty of the Mākaha for those aliʻi who honored their common heritage: the example of Kupakeʻi.

When Kamehameha conquered the district, he was tolerated but never really loved. Keawe-a-heulu ancestor of Kalakaua was made head man over the district, he was accepted because they had to, but as to real aloha, there was none. The loyalty and love of the Kaʻu people centered around Kupakeʻi, their own aliʻi. When Kamehameha wanted Kupakeʻi to live in his court and on his bounty [one of Kamehameha’s strategies for removing potential rebels was to invite them to join his court where they could be watched and controlled], the Mākaha people would not let him go. He was hidden away whenever Kamehameha’s canoes were seen approaching the shores. (Ibid.)

Pukui’s explanation of the origins of the people of Kaʻū begins with a reluctance to translate "Mākaha," their name for themselves. But once she traces the ancestry of these people (her own people) and provides examples of their behavior, she offers this observation: "Mākaha" has been translated as "Kaʻū the rebellious," but it also includes pride in one’s district, people and all, to the exclusion of all else" (Ibid.). The oli "ʻAʻole Au i Makemake iā Kona" is an expression of that pride in the very days when it was most threatened.

The oli begins with words of distaste for the district of Kona: "ʻAʻole au i makemake iā Kona." This distaste, however, is best interpreted as meant for the chiefs of Kona and not for the land itself. At the time of Kupakeʻi, the antagonism between Kaʻū (allied, for the most part, with Puna and Hilo) and Kona (allied, for the most part, with Kohala) was at least five generations old: Kamakau suggests that it had its origins in the mistreatment of Kuaʻana—a son of and a brother of Kupakeʻi’s great-great-great grandfather—by the Mahi chiefs of Kona and Kohala under the leadership of the high chiefess Keakamahana (Ruling Chiefs, 62–63). The feud, Kamakau continues, was played out over "several centuries" by successive generations of Kaʻū and Kona aliʻi; its "highlights" include:

1. The mutual enmity of Keaweʻīkekahialiʻi’s sons, Kalaninuiʻīamamao and Kalanikeʻeaumoku. Upon their father’s death, Kalaninuiʻīamamao (whose mother was a chiefess of Kaʻū and a prominent member of the ʻĪ family) was given the rule of Kaʻū; his half brother, Kalanikeʻeaumoku, was given the rule of Kona-Kohala. Not long afterwards, Kalanikeʻeaumoku had Kalaninuiʻīamamao assassinated. (Fornander, Polynesian Race, II:132–133).

2. The conflict between Kalaniʻōpuʻu and Alapaʻi. Kalaniʻōpuʻu succeeded his father, Kalaninuiʻīamamao, as aliʻi nui of Kaʻū; his mother was a Kaʻū chiefess and a granddaughter of ʻĪ. Alapaʻi, on the other hand, was a descendant of the Mahi family; he gained control of Kona and Kohala (and nominal control over all Hawaiʻi island) by defeating Kalanikeʻeaumoku. Kalaniʻōpuʻu rebelled against Alapaʻi and regained authority over Kaʻū by defeating Alapaʻi at the battle of Mahinaakaka. (Ruling Chiefs, 76–77.)

3. The conflict between Kalaniʻōpuʻu and Keaweʻōpala (son of Alapaʻi and aliʻi nui of Kona). After a prolonged series of battles in South Kona, Kalaniʻōpuʻu defeated Keaweʻōpala and, in 1754, became ruler over the island of Hawaiʻi. (Ibid., 78.)

4. The ongoing hostility between Keōuakūʻahuʻula and Kamehameha I. Keōuakūʻahuʻula was a high chief of Kaʻū; his parents were Kalaniʻōpuʻu and Kānekapolei. Angered by the redistribution of lands that followed Kalaniʻōpuʻu’s death, Keōuakūʻahuʻula joined his half-brother Kīwalaʻō against Kamehameha and the Kona chiefs. Kīwalaʻō was killed at the battle of Mokuʻōhai (1782); Keōuakūʻahuʻula escaped to rule Kaʻū and Puna. This began nine years of warfare between the two chiefs; the fighting ended with Keōua’s death at Kawaihae in 1791. (Ibid., 119–122.)

With Keōuakūʻahuʻula finally out of the way, Kamehameha sent Keaweaheulu to rule over Kaʻū. Keaweaheulu, a counselor of Kamehameha’s and one of the four great Kona chiefs of his time, had earlier come to Kaʻū to invite Keōua to the "meeting" at Kawaihae. Now this "betrayer of Kaʻū’s...lost aliʻi" (Polynesian Family System, 232) returned to supplant Kupakeʻi as aliʻi nui of the district. Kaʻū was stripped of its sovereignty, its hereditary line of succession was subverted, and its ranking aliʻi was condemned to exile in his own land.

The effect in Kaʻu was—the broken spirit of a proud and fiercely independent people, who lost at one treacherous blow the . . . flower of their native aliʻi and came under the hated rule of the conqueror. Kaʻu Makaha—"Kaʻu the fierce"—was humbled, their proud title brought to shame. The grandparents of oldsters yet living will attest to the withering character of this thing. Songs, chants, stories bear witness . . . (Polynesian Family System, 232.)

Kaʻū responded as best it could. The Mākaha acquiesced to Kamehameha and his administrator but gave their aloha quietly and stubbornly to Kupakeʻi. Of Kupakeʻi they would privately say, "He alone has the right to bake our heads" (Ruling Chiefs, 205n). That which they could not express in the presence of the outsider they whispered to their children and hid away in their poetry. One of those poems was Kupakeʻi’s mele inoa "He Inoa no Alakaihu Oia o Kupakei." Its first sections contain a lengthy tribute to his descent from ʻĪ of Hilo and Kaʻū:

That is your name, thou direct descendant of ʻĪ

You are of ʻĪ-kanaka, O answer to my call

Answer to your ancestral name of ʻĪ.

The formal tone, attention to genealogy, and emphasis on chiefly kapu reflect the politics of Kaʻū and Kona at the time of Kalaniʻōpuʻu and identify these sections as having been written at Kupakeʻi’s birth. As the chant progresses, however, this conventional, public poetry gives way to personal expressions of love for Kaʻū and defiance of outsiders. The shift in emotion and focus seems to reflect the insecurities of the war-torn reign of Keōuakūʻahuʻula and leads us to believe that the complete chant was composed in increments, probably by different haku mele, over the course of Kupakeʻi’s life. We believe that our paukū, "ʻAʻole Au i Makemake iā Kona," gives evidence of a third shift in emotion and focus—to stubborn pride, defiant exhortation, and creeping anguish—that moves us into the period of Keōuakūʻahuʻula’s death and Kupakeʻi’s "exile." The paukū begins with what sounds like a survivor’s distaste for the treachery of Kona. Kamakau reports that, upon approaching Kawaihae, Keōua divided his party into two groups: those who would die with him, and those who, through proximity to Pauli Kaʻōleiokū, would live (156). Those few who were spared, returned to Kaʻū by way of Kona. I did not care for Kona; I have Kaʻū could easily be the words of one who returned to his broken homeland and, despairing himself, struggled to inspire and rally his despairing people.

The paukū turns quickly away from Kona, leaving the impression that Kona, like its chiefs, is now to be ignored. All that need be said about Kona is contained, understated, and dismissed in the first line; the paukū is not a point-by-point comparison of the merits of the two districts, it is a description of Kaʻū alone. Literally, it is a description of water: of inaccessible underground water at South Point that flows night and day into deep ocean springs, of precious condensation that drips off vegetation and cooling rocks where it is sopped up with kapa sponges and wrung into water gourds, of water that must be dived for at Mānā and Unulau, of water that collects after rainfall in the eye sockets of fish, and of water that is given to children in their own small hue wai so that they will learn, at an early age, to value and conserve the precious fluid.

Figuratively, the paukū’s catalog of water sources is meant to describe, remind, and rally a people who are fiercely proud of their ability to survive. They alone are able to find water—and thus, life—in a land that others reject as forbidding and desolate. In this salute to Mākaha endurance, the poet subtly exhorts his people to survive yet another difficulty: the defeat of Keōua and the rule of the outsider. "Kūlia," he says. "Strive. That is what we did upon hearing that our land was without water, so must we strive today when we hear our wealth again denied." In this context, the underground water of Ka Lae that Kamehameha tried unsuccessfully to mine in 1815 (Ruling Chiefs, 204–205) becomes a metaphor of resistance, of Mākaha pride that must continue to flow, untouched and unabated, beneath the impenetrable pāhoehoe of the homeland. The patience required to obtain water from dewfall, from underwater springs, and from the eye sockets of fish-remains becomes a metaphor of the patience required to sustain Mākaha unity in the face of a new drought. The care with which children are taught to carry and conserve their own water supply—and the haunting song of the wind as it plays over the mouths of their water gourds—become an eloquent metaphor of the importance of oral tradition, of poetry like this very mele inoa, in teaching each new generation of Mākaha to carefully hold and preserve its heritage.

The central sections of both Kupakeʻi name chants are rich in water references of this sort: they speak of how the Mākaha bristle at the suggestion that Kaʻū is without water, delight in drinking that which the outsider regards as unpalatable, and fiercely remind each other to keep their wealth from outsiders. One paukū of "He Inoa no Alakaihu Kupakeʻi," for example, reads:

The hollow in the bosom of a rock,

The fine drops from the broken hollow of a kukui tree,

There is found water that smells like acrid smoke,

Life is found in the flowing water at the haunts of birds,

Their existence is hidden, the native denies it to strangers...

Let me hide the water lest others see,

Hide your share, you [Mākaha] chiefs who rule the land.

[HEN III:929–939; Pukui translation.]

There is a significant difference, however, between paukū like these and "ʻAʻole Au i Makemake iā Kona." Sentiments in the former group derive from a Mākaha who were threatened but still in control of Kaʻū ("Hide your share, you chiefs who rule the land"); the proud language of these paukū runs undiminished and unquestioned from beginning to end. The language of our own paukū is colored by the sorrow and perspective of those who have survived an almost unbearable defeat. Pride is evoked only after its context is defined ("I do not care for Kona’s rule"). Pride is interrupted by an exhortation for a renewal of proud effort ("Strive"). Pride carries the first 14 lines of the 19-line paukū; it then gives way to quieter morale building ("Be thankful for your blessings here and now"), frank appraisal of loss ("There is no going back, ways are different"), and wise advice for sanity and survival (Look forward with love . . . Let pass the season that is gone").

Although the names of the poets of "He inoa no Kupakei oia o Alakaihu" are unknown and much of their language is obscured by the 180 years that stand between us, we interpret the mele’s fifth paukū as a turning point in the emotional journey of the complete name chant as it moves from the ancestral glory of its opening verses to the gnawing uncertainty of its closing lines: "Turn to look at the heights of Wahinekapu / Where the chief’s ʻōhiʻa blossoms are being picked, / What am I to do about it?" Some of us who perform "ʻAʻole Au i Makemake iā Kona" are Mākaha, gourd-carrying children of children whose great-grandparents remembered windsong on gourds’ mouths. Some of us are equally the descendants of Kona. Others of us descend from neither. But all of us, without exception, stand at the transition place defined by this oli; such is the nature of our time. We do not care for the "Kona" of this age. That which we cherish is "wai ʻole" in the eyes of the other; it is too subtle, too difficult, or too deeply buried for his energy and taste. But it is still there to sustain us, and we are still here to hold to it. Hold to it we must.

The essay above was written by Kīhei de Silva and excerpted from his Hālau Mōhala ʻIlima Merrie Monarch Fact Sheet of 1992. It is offered here, in slightly revised and updated form, with his express consent. He retains all rights to this essay; no part of it may be used or reproduced without his written permission.

photo credit: Creative Commons

Ka Lae, southernmost point and historic fishing site on Hawaiʻi. The people of this ‘āina wai ‘ole took pride in their resourcefulness. The water of Ka Lae, they said, "ran" day and night; it could be wrung from dew trapped overnight in kapa; it could be found in the eye-sockets of fish; it could be heard in the whistling water gourds carried by children who were, themselves, descendants of a single water-gourd ancestress.

photo courtesy of: Hālau Hāloa

Kumu hula and master chanter Anthony Lenchanko. His rendering of “‘A‘ole Au i Makemake iā Kona,” recorded 35 years ago on the audio cassette Nou e Kawena, continues to be the definitive version of this defiant mele oli of the people of Ka‘ū Mākaha.

photo credit: Meutia Chaerani, Wikimedia Commons

Windswept Ka Lae at Ka‘ū, Hawai‘i.