Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kīhei de Silva

Sources: 1) Joseph ‘Īlālā‘ole, Mader Collection, Ms Grp 81:7.23, Bishop Museum Archives, Pukui translation. 2) J. P. Hale, Roberts Collection, Bk.26:87 and Rec. H.82b, Bishop Museum Archives, also in BMA Audio Collection 1.3a.10, Pukui translation. 3) Helen Roberts, Ancient Hawaiian Music, Honolulu 1926:278–279, a published version of Hale’s text. 4) Maiki Aiu Lake, Papa ‘Ilima repertoire, July 1975, ‘Ilālā‘ole’s text as given to her by Pukui, Pukui-derived translation. 5) Ka Po‘e Hula Hawai‘i Kahiko, a video compilation of hula filmed and recorded by Huapala Mader (between 1930 to 1935) and released in 1984 by Bishop Museum, a short segment features ‘Īlālā‘ole performing two verses of "‘Āhia." 6) Nona Beamer, Na Mele Hula, Honolulu 1987: 6–7, ‘Īlālā‘ole’s text, Beamer translation.

Composed: 1) For Kupake‘i (c. 1780) as a mele inoa (note in Mele Card Catalog, Bishop Museum Archives); Māpuana de Silva, ‘ūniki class notes accompanying text taught by Maiki Aiu Lake). 2) For the infant Joseph ‘Īlālā‘ole (b. 1873) by his grandparents as a hula noho with kālā‘au (notes to Mader Collection of ‘Īlālā‘ole’s text). 3) By the cowboys of Kahuku Ranch, Ka‘ū, in 1875 as a "mele hula with puili, uliuli, or paiumauma" (notes to Roberts’ manuscript and Ancient Hawaiian Music). 4) As a hula kālā‘au in around 1875 in Ka‘ū and given to ‘Īlālā‘ole by his grandparents (Betty Tatar’s narration to Ka Po‘e Hula Hawai‘i Kahiko). 5) As a cleverly disguised mele ma‘i (introductory notes to Beamer’s text in Na Mele Hula).

Text below: Joseph ‘Īlālā‘ole as recorded by Mader in Ms Grp 81:7.23, Bishop Museum Archives. Parenthetical "E" are those taught by Maiki to her ‘Ilima class.

Translation: Kīhei de Silva, based for the most part on Pukui’s different translations of the ‘Īlālā‘ole and Hale texts.

A luna au o ‘Āhia, aha!

Ha‘a ana ka lehua i ka wai

E inu i ka māpunapuna, aha!

E māpu mai ana ke ‘ala

Ke ‘ala o ka lau hinahina, aha!

(E) hina iki a‘e nō kāu

Ka lawena a ke hoa akamai, aha!

Niniu poahi ka nahele

(E) hele nō ‘oe a mana‘o, aha!

Eia i ‘ane‘i ko aloha

He aloha ke kumu i hui ai, aha!

(E) ‘ike ‘ia nā pali Ko‘olau

Ha‘ina ‘ia mai ka puana, aha!

Ha‘a ana ka lehua i ka wai*

I was all the way up at ‘Āhia,

Where the lehua bends low into the water.

Let us drink from the bubbling spring,

The fragrance pouring sweetly forth.

The perfume of hinahina leaves,

Let us "tumble" a little.

The gentle movements of the skilled companion,

The forest spins dizzily.

You are now convinced,

That the one you love is right here.

Love is the cause of our union,

Known are the Ko‘olau cliffs.

This ends the song,

Of the lehua bending low into the water.

My wife Māpuana de Silva learned "‘Āhia" on July 3, 1975, as part of the ‘ūniki repertoire of Maiki Aiu Lake’s second class of kumu hula, the Papa ‘Ilima. Maiki had taught "Ua Nani ‘o Nu‘uanu" as the hula noho / hula kālā‘au number for her first ‘ūniki class, the Papa Lehua, but for the ‘Ilima she chose differently.

At that point—with ‘ūniki less than two months away—we were learning a lot of hula noho with instruments ("Pu‘uonioni," "Nani Wale Ku‘u ‘Ike ‘Ana," "No Ke Ano Ahiahi," "Eia Hawai‘i"), and we were learning them at the rate of one a week. The dances that Aunty hadn’t taught to the previous ‘ūniki class were often the ones she taught with her notes in front of her: she’d look in her book, read it off the paper for us to listen to and copy, or just read it to herself, and then teach it to us. "‘Āhia" was one of those. She hadn’t taught it to the Lehua class. It seemed like she’d learned it some time ago, and she needed her notes to jog her memory. We didn’t get any real explanation about the dance; she taught it and we learned it. But I know that I learned it well because at that point in our training I was just taking everything in so fast. I tried to write down everything that Aunty said when she talked to us, but for "‘Āhia" all I wrote was: "for Kupakei." That might have been all the information she gave us; I can’t remember anything else about its background. When we had our 10th year reunion, "‘Āhia" was one of the dances we decided to do, but I had to help the others. No one else remembered it very well. I did because it was hula noho—my favorite style—and because I’d been teaching it in my hālau. Except for one Merrie Monarch in the early 80s when my hula brother Keahi [Chang] taught it to Lāhela’s Miss Hula entry [Tracy Keli‘iho‘omalu, a student at Lāhela Ka‘aihue’s Lamalani Hula Academy, 1983; Lāhela was a member of Maiki’s Papa Lehua and, consequently had not learned "‘Āhia"], I haven’t ever seen or heard of anyone doing it. I’m sure we’re the only hālau that dances it regularly; we might be the only group that knows it, period. [February 2, 1995.]

Over the years, in the course of many conversations with Lani Kalama—Maiki’s cousin and hula sister—we’ve managed to collect various bits of information about Maiki’s training in hula kālā‘au: "Ua Nani ‘o Nu‘uanu" was part of Lani and Maiki’s own ‘ūniki repertoire with Lōkālia Montgomery; "‘Āhia," on the other hand, was a dance that Lani and Maiki learned afterwards from Kawena Pukui. "It was one of three that Kawena shared with us, the others were ʻKalalea’ [ʻNani Wale Ku‘u ‘Ike ‘Ana’] and ʻWahine Hololio.’ Something happened, though, and I only got to learn the beginning of the kālā‘au number; Maiki was the one who learned it all." We find it interesting that Kawena did not teach Maiki either of the two kālā‘au numbers for which Kawena is best remembered: "‘O Kona Kai ‘Ōpua," and "Ke Ao Nei," the latter being Kawena’s own composition. We don’t know yet whether Kawena offered any reasons for teaching them ''‘Āhia," or whether she said anything about having learned "‘Āhia" from her cousin Joseph ‘Īlālā‘ole when she studied under him from 1935 to 1938. These are questions we hope to have answered in the course of future conversations with Aunty Nana (Lani); the "trick" with such talks, however, is that Aunty Nana’s memory is much better when she is allowed to reminisce freely.** Direct questions usually get us "I-don’t-knows" that, if we’re lucky, are answered elsewhere in unprompted conversations. She remembers "‘Āhia’s" tune: "I’ve always loved the leo; it’s the same way that you do it but different because of Kawena’s high, thin, sweet voice." As for the meaning of the mele, Aunty has had this to say: "Back then, if Lōkālia and Kawena taught kaona, I didn’t care about it. It’s only now that I’m almost makapō that it’s become important to me."

In the past year, over in the course of many visits to the Bishop Museum Archives, we’ve also managed to compile a fairly extensive bibliography of "‘Āhia" texts and "‘Āhia"-related material. A summary of this research appears in the opening section of this essay, unfortunately that summary contains so much contradictory information that it creates more questions than it resolves. According to our summary, "‘Āhia" is six types of mele written for three different reasons by three different sets of authors on three different occasions that span almost 100 years. What gives?

We believe that this confusion is not so much the result of inaccurate information as it is a reflection of changes in the ownership, function, and length of "‘Āhia" over the last two centuries. Our research suggests that the chant was originally a mele inoa composed for a chief born in the late 1700s; that it was given to that chief’s grandson almost 90 years later; that it was probably converted to mele hula—given a tune and put to dance—at the time of that grandson’s infancy; that it was picked up shortly afterwards by ranchers of a nearby district who added several risqué verses to the original; that this longer version became, probably by the turn of the 20th century, an all-purpose hula that could be danced with a number of instruments in a variety of styles; and that the version that survives today—though it is based on the grandson’s mele of the late 19th century—is simply thought of as a love-and-nature hula with a catchy tune. Mader and Tatar, then, are not wrong to identify "‘Āhia" as a grandparents’ song for their grandson. Nor is Roberts entirely incorrect in calling it a paniolo song. Nor is Beamer terribly off base in responding to the mele’s sexual imagery by labeling it a mele ma‘i. As "‘Āhia" changed hands over the centuries, it became a little of everything. Each informant offered the text of his time and place; each collector faithfully recorded that context; each had his piece of the truth. Those few who enjoyed a broader perspective, who knew of earlier texts and contexts, either kept silent or left a few well-placed hints. Because of modern "tools"—computer-accessed archives, audio tapes, and video cassettes—we find ourselves closer to sharing that same perspective than were the majority of "‘Āhia’s" recipients; it is certainly a broader perspective than Māpuana’s own teachers, Maiki and Nana, were allowed. Because we can play with more pieces of the "‘Āhia" puzzle, we can begin to integrate its many versions, explanations, and hints into a rough outline of the mele’s transition from name chant to love song.

* According to a note in the Museum’s Mele Index Card Catalog (which has since been supplanted by electronic database), "‘Āhia" was once a "mele inoa for Kupake‘i, chief of Ka‘ū" during the time of Kamehameha. Because the archives contain no version of "‘Āhia" to which "He inoa no Kupake‘i" is specifically attached, we can only surmise from the rich sexuality of all the existing versions that this early name chant offered a metaphorical description of the circumstances and setting of Kupake‘i’s own conception in the last decades of the 18th century. We suspect that the index card note was supplied by Kawena Pukui, a descendent of Kupake‘i and a keeper of the poetic tradition of Ka‘ū; our suspicions are supported by an identical note recorded by Māpuana in the margins of the text she received from Maiki who, in turn, must have received the information from Kawena.

The earliest existing version of "‘Āhia" is that given to Mader by ‘Īlālā‘ole. The hula ku‘i structure of that mele (couplets of regular length, stable meter, line-limited meaning units, the ki‘ipā, and the ha‘ina ending) is characteristic of the late 19th century and not of the less regular, through-composed poetry of Kupake‘i’s time. Still, the nature imagery of ‘Īlālā‘ole’s "‘Āhia," its emphasis on water, its lyric (subjective and sensual) tone, and its beautiful simplicity of phrasing are very similar to the central paukū of both of Kupake‘i’s lengthy, multi-sectioned mele inoa: "He inoa no Alakaihu Kupakei" and "He inoa no Alakaihu oia o Kupakei" (Hayselden chant book, M1. 89; Roberts Collection, Bk 23). We hypothesize that the original "‘Āhia" was one paukū of a longer Kupake‘i name chant, and that it was later adapted to the poetic style of ‘Īlālā‘ole’s own time.

We also hypothesize that the "‘Āhia" of this early mele inoa referred to more than a now-forgotten spring and ‘ōhi‘a grove in the lush uplands of Kahuku or Wai‘ōhinu. It may have also been an allusion to Ahia Kalanikūmaiki‘eki‘e, a descendant of Ahu-a-‘Ī, a wife of Kalaninui-‘ī-a-mamao, and a prominent chiefess of the Ka‘ū-Mākaha line to which Kupake‘i belonged. This same Ahia is a direct ancestress of Queen Emma, the ali‘i to whom ‘Īlālā‘ole and Po‘ai-wahine (Kawena’s grandmother) were deeply attached; we wonder if ‘Īlālā‘ole and Kawena’s knowledge of the chant "‘Āhia" was not doubly reinforced by their connection to the ancestress, the genealogical "spring," of both their Ka‘ū and Emma affiliations. (Fornander, Polynesian Race, II:129, 222; Lilikalani Genealogy, Micro. 232.1, BPBM.)

* Huapala Mader’s notes to the ‘Īlālā‘ole text identify "‘Āhia" as a chant composed by ‘Īlālā‘ole’s grandparents "for Ilala‘ole when a baby." She gives us no indication of who these grandparents were, but our genealogical detective work reveals a most interesting connection. One of Pukui’s notes to another chant in the ‘Īlālā‘ole repertoire ("Auhea wale ‘oe ka makani la / Malanai ho‘i a‘o Puna") identifies it as belonging to Libby "Libe" Mauka‘a, a first-cousin of ‘Īlālā‘ole (Ms. Grp. 81, Box 7.20). According to Pukui (Ibid.) and the "Ka‘u Chiefs" genealogy (Micro 2321.2, BPBM), Libe was also a granddaughter of Kupake‘i through her mother, Kaiahua; because her father was a haole (Thos. W. Martin), her mother had to have been a sibling of one of ‘Īlālā‘ole’s parents; in short, Libe and ‘Īlālā‘ole probably shared the same grandfather: Kupake‘i. We suggest that "‘Āhia" was originally a section of one of Kupake‘i’s own name chants, and that he gave it to ‘Īlālā‘ole as a birth present. The passing on of mele inoa to successive generations was a common practice in the old days, and it would have been quite simple for Mader to confuse the giver with the composer. ‘Īlālā‘ole, for his part, would have been reluctant to explain to an outsider like Mader the ancestry implicit in the chant. He was, after all, descended from Ka‘ū Mākaha, and as he told Kawena in a 1960 interview: "Ua pāpā ‘ia"—detailed public discussion of his genealogy is prohibited (Haw. 78.1.2, BPBM Audio Collection). But he must have shared the story of "‘Āhia’s" origin with Kawena—his cousin, niece, and hula student—who, in turn, left just enough of a trail for the rest of us to follow.

* Helen Roberts’ note to the J. P. Hale version of "‘Āhia" explains that the chant "was composed in 1875 at Kahuku Ranch, Kau, Hawaii" (Ancient Hawaiian Music, 278). Hale’s text contains nine two-line verses, four more than the version ‘Īlālā‘ole shared with Mader. Two of the additional verses "fit" the ‘Īlālā‘ole text in style and content and may have simply been withheld by ‘Īlālā‘ole when he performed for Mader. These are the seventh and eighth verses of the Hale text and begin with "Hele nō ‘oe" and "He aloha ke kumu;" the second of these was, in fact, included in the version Kawena gave to Maiki. The remaining Hale verses, however, are considerably less subtle and far more western than ‘Īlālā‘ole’s. These are verses five and six of Hale’s text and begin with "Hele a o luna" and "A he meli." Where ‘Īlālā‘ole’s text is built on the native images of bubbling water, swaying lehua, fragrant hinahina, and the forest’s dizzy spinning, these "cowboy" verses compare lovers to plump pumpkins, honey, and flowing milk. We suggest that these are the verses composed at Kahuku, and that they were appended in 1875 to the older and more delicate mele inoa.

‘Īlālā‘ole performs his version as a sitting hula with kālā‘au; his mele is sung with a distinctive hula ku‘i melody characteristic of the last quarter of the 19th century. Hale’s version retains the ‘Īlālā‘ole melody, but he indicates that the "mele hula" can be performed as "puili, uliuli, or paiumauma." We suggest that Kupake‘i’s original name chant was given a tune and choreographed with kālā‘au at the time of ‘Īlālā‘ole’s birth in 1873; it was prepared in this manner to honor ‘Īlālā‘ole himself. Within three years, that hula had become popular enough in Ka‘ū for the Kahuku cowboys to add their own spin to a text whose origin they may not have completely known. By 1924, when Roberts transcribed Hale’s cowboy-altered version, the mele had evolved into a playful, all-purpose hula whose connection to Kupake‘i had all but vanished.

Ironically, ‘Īlālā‘ole outlived these innovators, saw their version of "‘Āhia" fade into obscurity, and re-established his text and choreography as the standard of our time. To the best of our knowledge, the Hale version does not exist today as anything other than text and audio tape in the Museum’s archives. On the other hand, ‘Īlālā‘ole’s "‘Āhia" survives in the Kawena-Maiki connection, in the Beamer tradition, and in Mader’s text, dance notes, and film. We find it equally ironic, but hardly as satisfying, to realize that ‘Īlālā‘ole’s version has been reduced by time and entropy to a simple dance routine of words and motions; it is hardly the significant record of Hawaiian culture that it ought to be. We know this because of what the Papa ‘Ilima learned and didn’t, because of the explanation-less manner in which Māpuana herself has taught "‘Āhia" for 15 years; because of the pseudo-definitive nature of published explanations of the chant ("It wasn’t until I was married that I realized this was a mele ma‘i...disguised by an expert poet"—Na Mele Hula, 6), and because of what our year of research has taught and suggested.

Our mission, then, is to teach and present "‘Āhia" in a manner that reflects its origins and depth. It is not enough for Māpuana to say "Maiki taught this to me and now I will teach it to you." It is not enough to say, with a wink, "When you’re married you’ll really understand what this chant is all about." "‘Āhia" belongs to the proud and fierce tradition of the people of Ka‘ū. It belongs to the ancestral chief whose life encompassed the best and worst times in his people’s history. Name chants for Kupake‘i begin by tracing the glorious ancestry of the Ka‘ū-Mākaha; they end with haunting pleas to uphold that ancestry in the face of treachery, defeat, and change. One happy section of a Kupake‘i name chant—"‘Āhia"—was given to the infant grandson of that chief and was made into hula noho / hula kālā‘au in that boy’s honor. As such, the mele celebrates the survival of Ka‘ū. As such, the mele answers with joy the closing uncertainties of the chants from which it derives. Of course "‘Āhia" is about love-making, but this is not love-making that we simply wink at and chuckle over. "‘Āhia" is about the joyful act that leads to the children and grandchildren by which a people—not just the Mākaha—will survive and thrive.

The essay above was written by Kīhei de Silva and excerpted from his Hālau Mōhala ‘Ilima Merrie Monarch Fact Sheet of 1995. It is offered here, in slightly revised and updated form, with his express consent. He retains all rights to this essay; no part of it may be used or reproduced without his written permission.

* The following performance note was included in the judges’ copy of the Merrie Monarch Fact Sheet referred to above. I offer it here for those interested in examining more carefully the hālau’s performance of "‘Āhia" in the 1995 MM Festival. The text we perform is almost entirely Maiki’s as she received it from Pukui. To this we’ve added the one ‘Īlālā‘ole verse that Maiki did not learn (or that she decided not to teach); that verse, ‘Īlālā‘ole’s fourth, begins with "Ka lawena a ke hoa akamai." Our choreography is almost entirely that taught by Maiki to the Papa ‘Ilima. The two exceptions are: 1) we dance each verse twice; 2) our "Ka lawena"—not taught by Maiki—is based on Mader’s dance notes for the version that she learned from ‘Īlālā‘ole. In comparing Maiki’s choreography with the ‘Īlālā‘ole film-clip, we’ve discovered that Maiki’s hula kālā‘au, though quite similar to ‘Īlālā‘ole’s, is more simple and definite in execution. ‘Īlālā‘ole was well-known for the elaborate, free-flowing wrist-movements with which he embellished basic gestures. We assume that Maiki taught a "stripped down" model of ‘Īlālā‘ole’s fully loaded dance—one that her students could perform without injuring themselves.

**Elizabeth Ka‘aikawaha Kekau‘ilani Kalama (Aunty Nana) passed away on January 3, 1998. We foolishly took for granted her apparent good health and longevity; as a result, these questions were never broached or answered. Aloha nō.

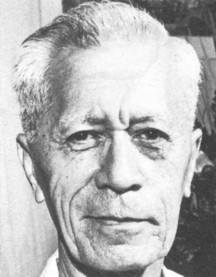

photo credit: Betty Atkinson

Hula master Joseph Keali‘iakamoku ‘Īlālā‘ole-o-Kamehameha (1873–1975). Born in Puna, Hawai‘i, ‘Īlālā‘ole descended from both Alapa‘inui and Kamehameha I. It is through another of his high-ranking ancestors—his grandfather Kupake‘i, a rebel chief of Ka‘ū—that ‘Īlālā‘ole inherited "‘Āhia," the hula kālā‘au that lives to this day as a result of the efforts of his cousin and student Mary Kawena Pukui.