Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kīhei de Silva

We carry a blue chair down from his front porch and set it in the shade of the guava trees in his front lawn. It is midmorning and Keahi Allen has driven us from our hula workshop at Kalōpā, Hāmākua, all the way to the end of the road at North Kohala to visit with this old-timer.

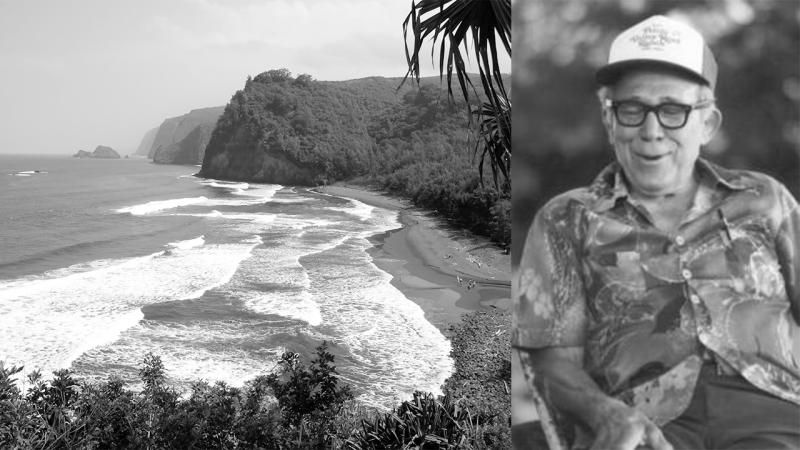

His is the last house before Pololū Valley drops into the ocean, and from the lookout across the street we can see the beginning of the Hawai‘i Island equivalent of Kaua‘i’s Nā Pali coast. Thousands of Hawaiians used to live here; his people were among them. The valleys were filled from mouth to four miles inland with lo‘i kalo. An entire valley—Honokānewai, the second one in—was deeded to his family at the time of the Māhele.

He was born here, “up at Māhiki; so you see I belong to this island.” He grew up here, and down at Kawaihae, and a little bit at Kamehameha Schools (until he left because he and his teachers “didn’t see eye to eye” over what a Hawaiian was). He worked for 40 years as the keeper of the 22 mile-long Kohala Ditch Trail—an engineering marvel built in 1903 to carry 50 million gallons of water a day out of the mountains to water the plantations of the dry Kohala coast. He spent eight more years as chief of the Hawaiian Village at the Polynesian Cultural Center in Lā‘ie (“I only wanted to stay for two years, but then my mo‘opuna started to go to college there, and I couldn’t run away from them”). And now he’s home.

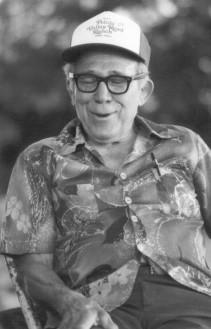

He appears at the back corner of his house with a load of orange carpet-runners in his arms. “You don’t want to sit on the wet grass while I tell my stories,” he says, “or you’ll get what we call kawaū ka ‘okole.”

When we’re comfortably arranged at his feet, he sits down and dries his hands on his knees. His pants ride up a bit, and I can see, between the hem of his left trouser leg and the rim of his black sock, three inches of shiny plastic leg.

His blue-and-white baseball cap reads, “Sproat’s Pololū Valley Ranches, Kohala, Hawai‘i.” He is the family patriarch—William K. Sproat—“the K is for Kāneakalā, my mother’s name.” Uncle Bill. He talks almost without interruption for almost two hours. Only once or twice does he repeat himself, and his stories are such that repetition is welcome. Twice his friendly part-Doberman nudges up to him and rolls on his feet. The dog is shooed off: “Scram and get outa here; you’re interrupting me.” But there is nothing mean in his tone, only firmness and love. This, I suspect, is how he treats all living things: people, his dogs, and above all, his mules.

When the talk is over, he invites us into the house he’s built (“Not bad for living in the sticks . . . you know some people think I’m crazy to live out here alone”), and then he takes us into his back yard so that he can pick gardenias for all the ladies. On the way to our vans, he points out a young ‘ulu tree that is already thick and bursting with life and leaves. “I must’ve done something right with that one,” he says. “It’s my mark on this place.” That’s the least of the marks you’ll leave, I think to myself as I shake his hand good-bye.

What follows are Uncle Bill’s words. Not all of them, but enough to treasure him by.

This mountain is a rare article. The make-up of the mountain is such that it is a little reservoir. We have what the geologists refer to as a dike system in this mountain. These dikes were formed by volcanic pressure. You know how a volcano builds mountains? One flow on top of another. Well, when this volcano was getting ready to quit, the interval between the flows became so long that the crust in the crater became so thick that when it became active it couldn’t shove the molten stuff straight up into the crater, so it just shoved it up in perpendicular strata. So we have a dike system.

You go up these gulches and you’ll see dikes only about 12 to 14 inches thick. But that rock, because it’s been shoved up with such terrific pressure, is so dense that it is impervious to water. So before these gulleys were worn down, I’m talking about eons ago, this mountain was all divided up into water-bearing compartments by these dikes. And this being the second wettest spot in the world, the rains eventually filled up these compartments. And when they overflowed, that’s what caused these gulches: the water continuously flowing down. And that’s B.H.—before Hawaiians.

When the Hawaiians came here, soil had formed in the gulches, so they terraced off all the bottoms and made taro patches because the water was continuously running—good for taro. So all the valleys from here to Waipi‘o were all like that. One time, people lived in all of them. I wasn’t here, but let me tell you the evidence. We go to the second valley, the one where the most water is. We have every available space in the valley, and that valley is quite wide, every available space was terraced off in taro patches from seashore to four miles up in the mountains. Even where the ditch is at the 1000-foot level. It was all taro, and that’s what made big Hawaiians out of little ones: kalo.

My mother’s family owned most of that valley; they were given it by the chiefs. We still own some of it, but when the missionaries took over—that’s some dirty guys—where my grandmother’s house is now, if she didn’t have a stone wall around her house that covers four acres, she would’ve been like my mother’s grandfather; all he got was one acre of his own land, I mean on the record. So all we own down there is five acres now. If my grandmother didn’t have that wall, she would’ve gotten one acre, too. That’s what the missionaries did to us. Had some dirty louts among the folks grew up in the valley here. My mother was born in the valley here. And when the white man came and kind of changed the whole set up here, the young men got in the ships and went away. I have three uncles I never even saw. I heard they’re in New York somewhere. And the women married other men and moved out of the mountain, too, so bumbye nobody lived in the mountains here.

My dad is a haole. He came here to overthrow the monarchy, that dirty lout. But he meant well. He come over here from Missouri. All his family was doing was farming, and because he was the youngest son, he thought he would see the world instead of farm. His idea of "go see the world" was to go up to Alaska, look for gold. So he said he was walking along the waterfront in San Francisco looking for a ship to go to Alaska when two men came up to him and asked him if he wanted to go to Hawai‘i to join the P.G. Army that later overthrew the queen. He was one of ’em. I got it straight from the horse’s mouth.

Of course, he didn’t know who Lili‘uokalani was; he just came here for the adventure. But when he got down here and found out what they were up to, he felt a little sick. He was a good American and believed in people’s rights, and here they were taking everything away from the Hawaiians. So he got out of the army as soon as he could.

So he and another guy, a Texan who felt the same way he did, decided that they would sail down to Tahiti. So they bought themselves a schooner. And neither one of them knew how to navigate, so they hired themselves a sea captain by the name of Goode. But he wasn’t good enough. No, he was, but it wasn’t his fault. They got hit by a hurricane and broke both masts. They just drifted for almost three months. They drifted clean back here and wrecked on the Kona coast.

They got ashore with only the shirts on their backs. They decided to split up. He came this way. He walked clear to Kohala and it took him almost five days. But he said that Hawaiians lived all along the coast. They saw what they called this "lonely haole," and he looked hungry, I guess, so they took care of him. Then he got here and got a job on the plantation.

He didn’t tell them he was only going to stay a few months, so when he got enough money he took off for Honolulu. Because he was a soldier in the P.G. Army, they gave him a job on the police force.

Now my mother was a school teacher here. She went to school under the missionaries and then taught school in the valley—that’s how many people were around here in them days. The kids from up here had to go down there to go to school. And so she went to Honolulu for some school work and met my dad, and they got married in January of 1900. My mother never liked it there and finally talked him into moving back to this island. So he bought 30 acres in Waimea. Sorry we never kept it. It’d be worth quite a bit of money these days.

I grew up part of my life in Kawaihae because my mother made the mistake of taking my dad down there to recuperate from a little touch of pneumonia that he had. When he saw the fishing boats, he went into the fishing business. So I grew up part of my life in Kawaihae, but I enjoyed that. It was good at the kahakai.

By that time had no more schools over here, so I went to Kamehameha. We’d go there and then come back in the summer time. I never quite got out of Kamehameha. I quit. The teachers and I didn’t see eye to eye. But my other sisters and brothers, they went high. One sister went to Columbia University, one went to University of Pennsylvania. Two brothers graduated from University of Hawai‘i. Me, I just quit.

But when I took my dad’s job up here, see, you gotta know something about water and civil engineering. So I had to go learn some more. I took side lessons. I was in charge here for forty years, so I been around for a while.

This Anna Lindsey’s husband, his father is the one that built the ditch. That was in 1903. See, all these people had plantations: there were five mills in this district. One belonged to the Hind family . . . they built the ditch because they needed the water when it was dry. And they built quite a ditch. There’s 12 miles in the mountains and 10 miles out here—22 miles of ditch. And in the mountains, 12 miles of it is all tunnel. And to cover that tunnel we have 40 miles of mule trail.

The tunnel is big enough to bring out 50 million gallons of water a day. You can go up in the tunnel on a boat. It’s a great engineering feat built on one-tenth of one percent. You know what that is? 1000 feet you go, only one foot difference in slope. Almost flat. That’s why you could push a boat up. But when you put 50 million gallons in there, you don’t walk up that current very far. Cut it down to 35 million. That’s about waist deep, and you can push a boat up it. And so we take all our heavy freight into the mountains by tunnel. And when you come down, you just sit and play ‘ukulele.

So this tunnel was built by the Hinds and this Anna Lindsey’s father-in-law, Perry, was the guy that built the ditch. And he was the first superintendent here till my dad came up. He was ready to quit, so my dad took the job, and I inherited it from my dad. I worked from ’28 to ’68, that’s how long I worked here.

They still work the trail, but they threw away that ten miles up at 2000 elevation. From ‘Awili on they throw away. You see, there’s seven main valleys from here to Waipi‘o. This is Pololū; the next one is Honokānenui. That is the main one on this side; it comes up and almost meets Waipi‘o at the top of the mountain. That’s why this valley has enough water for what the county now needs without taking water from farther back. What they take now is nothing compared to what the plantations used to take.

When I used to live in the valley, Honokāneiki, the third one in, we raised pigs, we went fishing, we planted all we needed. I was practically what they call "self-sufficient." I had cows. I milked my own cows. I had pigs. I killed my own pigs. We had no refrigeration then, so I salted them. I make dry meat; I make all kinds. And fish. When we wanted fish, no more refrigerator, just take your bamboo and go down there and come home with two moi about that size (gestures from finger-tip to elbow); that’s all you need. Had one point down there: talk about ulua. Just go there, cast: all kinds.

The biggest ulua we caught was 103 pounds. But this kind you don’t want; that’s just like catching a pig when you catch one that size. But you need one only about like this (same gesture: finger to elbow). And there’s plenty of those and easy to catch: you just go near the rocks, see, the big ones don’t go there. You catch those five, six, ten pound kind. O, I never lived higher on the hog than when I lived in Kāneiki. Talk about eggs. I used to give away to the Japanese by the bucket. I had cows. I put all the milk in the yard for the chickens, and the cats, and the dogs. And we had gardens there . . . raised all the vegetables you could want.

These are the valleys: Pololū, Honokānenui, Honokāneiki, Honoke‘a, Honopo‘e, then you jump clean across to Waimanu. There’s a long stretch there where a lot of little gulleys come down. But they are not cut down to sea level. And between Waimanu and Waipi‘o there’s 13 little gulleys like that. And the three rocks out in the ocean down there are called Nā Moku. They all have names. Paokalani is one, but I can’t think of the others. One has a puka right through it; you can’t see it from here; it’s outside of the big rock, and we used to go there on the canoes. It’s the home of the ulua over there. No can think of the other’s names. I’m getting old, I guess. I’ve been away too long. You know when you come back, you don’t talk like you talked to the old Hawaiians. You called everything by name, but now nobody knows the difference.

I lost my leg right up here, practically, when I worked the trail. I got on my mule at my brother’s place. And this was kind of an outlaw mule, anyhow, that I bought from somebody. I used to make that my business. See, my dad was from Missouri and he claimed that he was part mule because they raised mules. Mules—you always hear them talking about mules being mean. But really, mules are smart. They’re so smart that they’re smarter than most people. When you hear a guy that says a mule is mean, it’s because he’s dumber than the mule. The mule is smarter than him. When a mule knows that he can’t get away with bluffing you, he’ll do what you want him to do.

So this one I bought was one of those big husky mules. Nobody wanted him, so I bought him. I used to ride him up there, but one day he left his mark on me. I put the saddle on . . . my fault because I wasn’t careful enough. I put my foot in the stirrup and jumped on. He started to buck, and I bounced behind the saddle, on his ‘okole. It’s bad enough when you’re in the saddle, but when you’re on the ‘okole, he can really buck. And he threw me when he started running down the hill.

As I went off, one foot was still in the stirrup. I saw a rock, and I tried not to dive into it. I went over the rock, but my foot got caught behind it. I lay there on my face, but I didn’t feel too hurt. I turned over; when I lifted this leg, the bone came out. They flew me to a hospital in Honolulu, but they couldn’t put the leg back again, so they cut the leg off. But I get along fine with this leg.

So when I came back, my boss said, "You not going ride up the mountain no more now." I said, "Oh no; you don’t tell me what to do. You may be my boss, but I’m going up the mountain." So he said, "All right; you do what you want to do."

So I did everything I did before with my one leg—one good leg. And I been going yet. And here I’m eighty, going to eight-three now, and still going. I ride mule and I do everything yet.

photo credit: Kīhei de Silva

"This mountain is a rare article." Uncle Bill Sproat on the lawn in front of his home at Pololū Valley.

photo credit: Leimomi Khan

Uncle Bill and guests, June 1985. Front: Leimomi Khan, Jan Yoneda, Pat Nāmaka Bacon. Back: Māpuana de Silva, Kanaʻe Keawe, Edith McKinzie, Moana Stender, Lauaʻe Adam, Keahi Allen, Kīhei de Silva, Bill Sproat, Cy Bridges, Kalena Silva.