Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kristy Perez-Kaiwi

Mahalo to Ka‘iwakīloumoku for permitting me to share this mo‘olelo of my grandpa, Alva “Mahi” Kaiwi and his memories of a changing town.

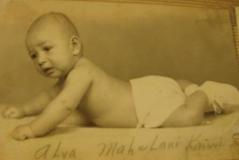

“We saw the town grow, we saw everything grow. There was no houses, no nothing.” These were the words of my grandpa as he sat with me sharing his reminiscent stories of younger days gone by. His name is Alva Mahealanipilialoha Kaiwi, father of three and grandfather of six. Born at Kapi‘olani Hospital in Honolulu, February 9, 1941, he was one of five children to Robert Kaiwi (of Hāna, Maui) and Josephine Maile Brown (of Wai‘anae, O‘ahu).

Growing up, they lived with his grandfather, tūtū man Kaua Kupihea, on an old fishing village located in the bay area of Nene‘u. Back then, the entire fishing village covered the area where the present-day Wai‘anae Army Rest Camp resides and Pōka‘ī bay stretches. The water was clear, clean, and extended beyond its present-day shoreline parameters. There were no jetties or piers; just the ocean, and the fishing village. Fishing, diving, and throwing net were taught to my grandpa by his tūtū man. Everyone in the fishing village had to know something about fishing; each person needed to contribute in some way. Tūtū Kaua Kupihea was a master in fishing and netting, and taught my grandpa how to determine what kinds of fish to look for. He was taught to throw net, lay net, “paipai” net, and surround net. There was so much fish to catch and so many ways to share it. In most cases, he gave all his fish away. Once in a while he sold fish, but “only for gas money,” he says. When the war broke out, the army needed a place of rest and recreation for the military. They wanted to use the fishing village area so they removed the village houses and relocated them to Lopikāne Street in Mā‘ili. There were fifteen families affected. After the war was over, the military promised to return the fishing village to the people, but that didn’t happen.

His days of throwing net are few and far between now. “No more fish…no more schools like before and the beaches are filthy,” he states. “It’s shame that we have to buy fish.” More and more people are fishing and netting small fish like ‘ōpelu and akule. “That’s what feeds the big fish. People are messing with the food chain. The fish are getting scarce,” he explains.

“There was only one road in Wai‘anae,” he continues. The main road today, Farrington Highway, was non-existent in those days. It was full of Kiawe trees and piggeries; there were no houses; just barber shops, tailor shops, and stores in the town. The old Wai‘anae town began near the Sacred Heart Parish on Old Government Road and ended at the old plantation theater (where Dansen’s Auto Repair is today). The small two-lane road continued to Pōka‘ī bay. “It was a 2-lane highway, and was so small, you gotta wait for one car pass-by,” he states as he continues to describe the length of the old road extending to Mā‘ili beach front. There was a lime quarry and a sugar cane plantation. “Everybody could tell if we played in the quarry or the sugar mill because we would come out either white (with powder) or black,” he chuckles.

He refers to Wai‘anae valley as “Puea,” a term I’ve never learned before. A tunnel located at the top of the valley was the source of an old flume. The flume had built-in gates for each farm lot in the valley. When farmers needed water, they would raise the gate and water would flow into their patches. My grandpa folks would catch ‘ōpae, ‘o‘opu, and crayfish in the stream located near the top of the valley. Everyone knew each other. Residents from the fishing village would share fish with the valley residents and the valley residents would share their crops. It was the traditional Hawaiian practice for this community. Sometimes, the fishing villagers would sell their fish to the markets; they would place the fish in bamboo baskets, salt it, and wait for the wagon (which came once a week) to take it town.

My grandpa started looking for a job at age 18. He was first employed by Southern Pipe as a machine operator at Campbell Industrial Park. At the time, there were only 3 companies located at the industrial park. The company Ameron bought Southern Pipe’s machinery and in 1964, my grandpa’s long career with Ameron began. Starting pay was $2.34 per hour; in 1964, this was a lot of money. He retired in September 1997, after 33 ½ years of service to the company.

Nowadays, he spends his time enjoying his home in the place known as “Puea,” fishing when the weather permits, hosting weekly family gatherings, and caring for his wife and youngest daughter. During family get-togethers, the elders sit together to talk-story and laugh about their funniest memories. My grandpa laughs with the others as they remember their kolohe days and drinking episodes. I enjoy listening to these great mo‘olelo, laughing along with them, and asking questions. I believe these stories should live on; I hope he shares more mo‘olelo with me. Thanks Papa!

photo credit: Kristy Perez-Kaiwi

Baby photo of Mahi Kaiwi

photo credit: Bob Krauss. Historic Waianae (1973), 137.

Pōka‘ī Bay, 1945

photo credit: Bob Krauss. Historic Waianae (1973), 137.

Old Wai‘anae Town in the 1920s

photo credit: Bob Krauss. Historic Waianae (1973), 137.

An old flume in Makaha Valley

photo credit: Kristy Perez-Kaiwi

Present-day photo of Mahi Kaiwi