Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

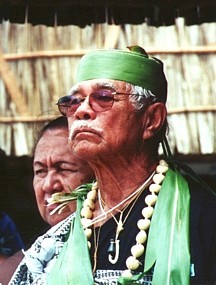

Kapalai‘ula de Silva

There is nothing special about his looks or dress. He is short, wiry, and grey-haired—considerably younger than my image of a 75-year-old, but still unremarkable. He wears boots, blue jeans, a black "Eia Hawai‘i" t-shirt, bifocals, and a beat-up green hat. You wouldn’t give him a second glance at Ala Moana Center, Pali Longs, or the Kokokahi YWCA workshop where I first get to know him. Luckily, though, I am prepared from the start to pay attention. My sister has already traveled with him to Aotearoa with the UH Mānoa Hawaiian language club. My father knows a lot about him from listening to Hawaiian language radio broadcasts of "Ka Leo Hawai‘i."

To them he is already a legend. They tell me that ‘Anakala Eddie Ka‘anana grew up in Miloli‘i where he learned and mastered the practices of fishing and taro farming from his grandparents, and where he was raised speaking ka ‘ōlelo makuahine, the mother tongue, of this land. They tell me that no one living today is closer to being Hawaiian than he is. "He is in his 70s, and he was raised by grandparents in their 80s," my father says, "so he is a direct link to people four and five generations older than you are. If you want to know what your great-great-grandfather was like, he’s probably right there in ‘Anakala Eddie."

Except for students in the Hawaiian language immersion schools, most kids don’t have a clue about ‘Anakala, and my bet is that even in schools like Ānuenue, hardly anyone has had a chance to spend three uninterrupted, 24/7 weeks with him. When I first found out that I had been selected as a member of the Hawai‘i Delegation to the 8th Festival of Pacific Arts in New Caledonia, I was truly honored. But what really got me excited was when I found out who would be the piko, the center, of our delegation and one of our two cherished elders, our hulu kūpuna: that would be Eddie Ka‘anana.

In order to take full advantage of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, I hung around him whenever I could—at airports, on planes and buses, at meals, meetings, and rehearsals, on dormitory steps and hallways, at Apia, Sydney, Noumea, Poindimie, and Auckland. Originally, I had hoped to get a handful of stories and impressions down in my journal as extra-special memories of the trip. What I ended up with was 22 pages of first-hand ‘Anakala Eddie narrative—something far more valuable than I ever imagined.

If I learned anything from my weeks with ‘Anakala, it is the absolute truth of traditional Hawaiian "indirection." He almost never tells anything important straight out. He offers his thoughts in usually round-about stories that start far away and only gradually work their way to his point. If you ask what he thinks about Jean-Claude Tjibaou’s statement that we indigenous peoples can’t afford to be chained to tradition, ‘Anakala Eddie will begin by explaining that he has no diplomas or advanced schooling, that his teachers were his grandparents and his school was the ocean, and he will end by telling you—quite a bit later—that we must remember the now almost-lost distinction between hele and naue. Both mean "go," but the second carries no connotations of "going" to one’s death. The message, if you can attend to his kaona, his hidden meaning, is that without the "chains of tradition," we’d all be sending each other to our graves. ‘Anakala, I have learned, requires patience and attention of a kind that we Westernized, mouse-clicking, channel-surfing Hawaiians are poorly prepared to offer. What he offers, I have learned, is well worth the effort. He offers an education in being more Hawaiian that can only be accessed by . . . being more Hawaiian.

October 17, 2000 – Honolulu and Sydney

‘Anakala Eddie describes the contents of his little red cooler as his pono lawai‘a—his fishing necessities. He is worried about passing through Customs at Sydney because of the ‘ala‘ala o ka he‘e preparation. This process begins with drying (kaula‘i) the squid’s ink sack, cooking it over a fire, adding something else to it (nanahu?), then wrapping it in lā‘ī and freezing it for later use. He uses this as maunu for baiting small hooks (also of his own making) to catch the small-mouthed fish like manini, maiko, and kole that aren’t normally taken by pole-fishers.

‘Anakala says that most modern fishermen scoff at his concoction: "Those fish will bite when the elephants grow feathers and fly away." But he learned this technique from his kūpuna, and it definitely works. The maunu, he says, is important on the Miloli‘i coast where the traditional fishermen of those villages maintained ‘opelu schools in the open ocean. They would make vegetable-food chum (pala‘ai; ‘ai, not ‘i‘o—vegetables, not meat) for the fish and feed them regularly so that they’d stay in the area and be easy to locate and catch. Meat or blood bait was forbidden because it attracted the predator fish—including sharks, ulua, barracuda, and marlin—that could wipe-out or scare off the ‘ōpelu schools. This bloodless vegetable-bait custom was also practiced near shore with reef fish; hence ‘Anakala Eddie’s recipe for ‘ala‘ala o ka he‘e.

‘Anakala Eddie says that Paige Barber wanted him to give his maunu demonstration at Windward Mall during our Pacific Festival of Arts hō‘ike, but ‘Anakala said that he felt very uncomfortable teaching about the sea in a shopping-center environment. He’d much rather teach it at the kahakai where he learned it and where he practices it. So he didn’t teach at the mall, but when Paige Barber called the next morning, they arranged a teaching and video session with the kids and teachers of Ānuenue School. They didn’t all go to the beach, but they did go outside where he felt right.

I notice that ‘Anakala Eddie is very practical and organized: he packed his pono lawai‘a in a single cooler, called the airlines to see if they’d accept it (they said okay in Honolulu, but they couldn’t guarantee approval when we stopped in Sydney), and brought a young man, Kawika, to the airport to take the maunu back home if the Honolulu desk of Air New Zealand changed its mind.

‘Anakala Eddie is now sitting comfortably in the lobby of our Sydney hotel. Dad joins him and asks, "Pehea ‘Anakala, ua ‘āpono ‘ia ka ‘ala‘ala o ka he‘e?" He gives Dad a big smile and nods. "Since I couldn’t bring the lei ‘awapuhi (that Uncle Kaha‘i Topolinski gave him in Honolulu) into Australia, I gave it to the customs officer before I checked through. After that, it was smooth sailing. I explained that my pahu kula (cooler) contained my pono lawai‘a: my net, my hooks, my line, my tools, and my other supplies. ‘A‘ole au i ha‘i, ‘o kēia ka ink sack of the octupus. He ha‘i wale nō. I just told them in general, and they let me through me ka wehe ‘ole i ka pahu kula. Without opening the cooler."

October 19, 2000 – Brighton Beach and Darling Harbor, Sydney

We gather in the hotel lobby to review our part in the greeting ceremony that will take place when we arrive in Noumea, New Caledonia. Uncle Kalani (the head of our delegation) describes the greeting sequence and exchange of gifts. He explains that we have been asked to refrain from giving tobacco as part of our ho‘okupu—although it has long been an important item in Kanak welcoming ceremonies, the Festival committee requests that visiting delegations refrain from promoting the evils of nicotine. This makes sense . . . until ‘Anakala Eddie offers his thoughts at the end of our meeting.

First ‘Anakala Eddie asks the other kūpuna in the group, particularly Kupuna Kauahipaula, if he may speak for them. He explains that he is always thinking of asking the kūpuna first—not only the kūpuna who are "visible," but those he carries with him, especially the grandparents who raised him. He explains, too, that he doesn’t try to figure everything out in advance. He waits until the time comes, and then these kūpuna help him to know what to do or say. When he is asked to travel with cultural exchange groups like ours, he always thinks, "Why come?" If it is just to look around and niele here and there, then there is no reason for coming. He must have a good reason. He agreed to come on this trip because of the importance of representing his kūpuna and sharing what they taught him. This is one of those times.

Now ‘Anakala moves to his tobacco point. He explains that the hā, or breath, is the first thing we do in this world: we hā mua. His mother’s mother grew paka, tobacco, and she would tell him the story of a lady—sometimes pretty, sometimes old—who would come and ask for paka. His grandmother told him, "When she comes again, you must share. It is Tūtū Pele." For his grandparents who raised him, "‘O ka paka ka mea nui." Tobacco was the important thing. It was not smoked all the time; rather, it was carefully grown, dried over a cooking fire, prepared, and smoked at special times—when you needed to think quietly, to relax and reflect on important matters. It is a way to focus on our hā. Even Tūtū Pele found value in paka.

His recommendation, very subtly made, is that we give tobacco at the welcoming ceremony. Who were we to deny this gift to our hosts, especially if they have the same feelings about paka and hā? "I am not an educated man. All I know I learned from the small fishing village of Miloli‘i. I had an opportunity to go to Kamehameha Schools, but my kūpuna asked me, ‘Na wai e mālama iā māua?’ Who will take care of us?" So he stayed home to care for them. And as a result, he sees and understands with eyes that even Kamehameha could not have given him.

I notice that ‘Anakala Eddie is always alert, on time, attentive, and ready to share thoughts and jokes with those who are willing to listen. On afternoon break, we wander through the Victoria Station area of Sydney where he and Dad try their hand at ordering Australian coffee. He gets a "short black"—because it sounds interesting. Dad, for the same reason, orders a "flat white." Dad’s turns out to be "palatable," but ‘Anakala is served some thick, syrupy stuff in a tiny cup. ‘Anakala jokes that it looks like it belongs in a child’s tea set. We get a big laugh out of this, and "short black" becomes part of ‘Anakala’s growing story of our trip to Nū Kaletoni.

Dad asks ‘Anakala Eddie if he’s been to Australia before, in his wā kelamoku (sailor days). He says that when he was in the Navy, he sailed all over the Pacific, from Alaska to Australia (but he never came ashore here); he was even on the Yangtze River in China. Later, as a crewman on a US government research vessel, he again sailed all over the Pacific -- but still without setting foot in Australia.

‘Anakala looks hard at Dad’s "Hawaiian Buffalo" t-shirt and says that it reminds him of his childhood. In the evenings, after each long day’s work was over, his family would gather to share stories. One evening, his grandfather asked if anyone knew about "kēlā holoholona ‘o ka buffalo." None of the kids knew, so he asked his wife to get a nickel for everyone to look at. He showed them the buffalo on one side and the ‘Ilikini on the other. Then he turned the nickel over and over, front to back, and said: "Here is how Maleka treats its ‘ōiwi (native people). They put the Indian’s nose in the buffalo’s ‘okole. And under that, they write, ‘In God We Trust.’"

When we return to Darling Harbor, we stop at an outdoor cafe for ice cream and water. ‘Anakala Eddie can’t believe that we have to buy water. "I won’t drink it if I have to buy it. Only if it can’t be helped. Because this is ka wai a Kāne (the water of Kāne) and it should be free to all." The principle, I think, is that of birthright. Water is a gift from Kāne to man, and the gift is defiled when men commodify it.

‘Anakala Eddie also talks a little more about tobacco growing and preparation as practiced by his grandmother. The leaves are picked when they’re not quite dry, then knotted and hung over a wood cooking fire where they are cured. He says that his grandparents took tobacco and gin when they visited Ka Lua o ka Wahine. These items are favorites of Tūtū Pele. The manner in which she received the paka indicated her temperament or intentions. His kūpuna could tell when Tūtū Pele was going traveling—erupting on the distant flanks of the volcano—by, I think, the way the flame and smoke flared up when the gift was accepted. They knew what the smoke foretold, so they were never surprised by new eruptions.

We got to Gavala, an indigenous art center in Darling Harbor. ‘Anakala sees, at the back of the gallery, a small, dark painting of a logging operation. Trucks in the foreground are hauling off fresh-cut trees; the forest in the midground is half-standing; looming above the trees in the top left corner of the painting is the grief-stricken face of a native woman, an Aborigine. The title: "Mother Nature." ‘Anakala brings it over with tears in his eyes, holds it up for a second for me to see, then takes it back to its place. The he returns to my section of the gallery and kneels to touch all the wooden objects lining one wall—animal carvings, baby boards, etc. Later, he tells Mom that the picture reminded him of his wā kamali‘i i Miloli‘i. When he was a boy, he watched the upland koa forest decimated by loggers. All the trees were felled, dragged to the shore, and hoisted on to small boats that, in turn, ferried them out to the bigger steamers waiting in deep water. One log was so big that it took two small boats to carry it. Now there is no koa forest above Miloli‘i, and as far as he knows, he’s the only one left to remember it. It shows, he tells Dad later, what people will do to make their pu‘u kālā, their hill of money.

Mom and Dad buy "Mother Nature" as a gift for ‘Anakala. He doesn’t know, and they are planning to surprise him with it later, i ka wā kūpono—when the time is right.

‘Anakala’s pāpale is green leather with a hatband of braided cord; it has several large holes in the crown at the front. He says his daughter bought it for him on a trip to Mexico, and he has worn it ever since. He has no intention of getting a new one. The holes on the top, he says, are just fine for cooling his head off. Then he tells me a short story about the paniolo—the Hawaiian cowboys—and their hats. ‘Anakala says that paniolo never get rid of their hats because they hold so many memories of events gone by. So, when their hats become too worn to wear, they hang them up in their rooms as a reminder of all those good times.

October 20, 2000 – From Sydney to Noumea

On the elevator after breakfast, ‘Anakala Eddie says, "I’m used to getting up early, 4:00 a.m. or so. When I got up this morning and looked outside, it was beautifully clear. I could see the sand and kai, and thought it would be a nice time to go walking. But then I told myself, ʻNo, it’s not the time to go walking. We aren’t at our final destination. I have to stay put and think of where we’re going and what I have to do there.’" He has to give a speech in Noumea; it is very much on his mind.

‘Anakala is always prioritizing. He constantly asks himself, "What is appropriate?" He constantly views his actions and decisions in light of his kūpuna and their example and instruction.

‘Anakala Eddie begins his speech at the Noumea Airport with a call to that which is above, below, and within. He asks this presence to join with us here in an embrace of welcome. He then refers to our island chain—from Maunakea, Hawai‘i to Pu‘uwai, Ni‘ihau—saying that we come here as one with reverence and aloha for all. He then uses the metaphor of a canoe to explain our travel and arrival: we have slipped our canoes into the sea of Hawai‘i, and the winds have carried us here to your shore. We have come with aloha and reverence to share with you the teachings of our kūpuna and to learn from you the teachings of yours. We come with aloha and ihi for all. He delivers this speech with his hat held in his right hand; occasionally, he gestures with his left; his voice not loud, but clear. As he gets more into the rhythm of his oratory, his style becomes almost kepakepa, and he sprinkles his speech with Ni‘ihau ts—to kātou mau tūpuna—for example. Another feature of his oratory: he pauses at regular intervals to translate into English. He later tells Dad that he learned this when he went to Aotearoa with the UH Mānoa language club. The elders there said they appreciated a translation because it helped them verify what they thought he was saying. He doesn’t know French, so he can’t make that translation here, but he hopes that English will at least give some listeners a clue.

Uncle Kalani has decided that ‘Anakala Eddie, as the senior male member of our group, should stay at the hotel with him and Kupuna Kauahipaula. The rest of the delegation is staying in the dorms at Dokamo, a school in the hills above Noumea. ‘Anakala only learned about this on the way to the bus after our airport reception. He didn’t show any disappointment, but Mom and Dad were betting that the decision wouldn’t last for more than a night or two. Sure enough, when Uncle Kalani brought ‘Anakala and Kupuna Kauahipaula to our Dokamo welcoming ceremony, ‘Anakala took Dad off to the side and said that he’d be back with us the next day. Although the hotel was much more comfortable and convenient, his place, he had convinced Uncle Kalani, was with the group. That was his purpose in coming.

October 21, 2000 – Settling into Dokamo School

‘Anakala and Kupuna Kauahipaula come to Dokamo for lunch. ‘Anakala brought his paiki (suitcase) with him, and Dad settles him into the dorm as soon as they have a spare moment. Dad’s getting a big kick out of the living conditions: there are now five men in his tiny, two-boy room. ‘Anakala is the only one who fits his bunk bed; the others are hanging over the sides, dangling over the ends, and sagging dangerously low in the middles.

Our group gathers to sing and wait for the bus to bring Haili‘ōpua Baker and her hanakeaka contingent to Dokamo. They have had to travel here separately and are a day behind us. When they do arrive, we stand at the entrance to the women’s dormitory and got through a short version of our standard ceremony: the kumu chant first, then the group chants "Eia Hawai‘i," then ‘Anakala delivers a welcoming speech addressed to the ‘ohana that has come safely from our distant home. This time, though, he opens in a high-voiced, ‘i‘i-filled style that clearly signals an upwelling of emotion and affection.

Afterwards, a group of dancers gathers at his side and feet to listen to stories of his Aotearoa trip and his explanation of his speech last night at the airport. He tells of naming a child in Orakei, Auckland, for the rainbow that appeared and followed them there: Kapi‘ookeānuenue. He tells about wanting to contact the family and send a gift for the baby’s first birthday, and about an unfinished jade pendant given to him by the people of the Wairua marae. He says that he had to think long and hard about the significance of an unfinished object ("My kūpuna taught me never to leave a thing unfinished"), and he finally came to the conclusion that they wanted him to return ("So that they can finish this pendant"). He says that he later asked two Maori elders about his interpretation. After a long discussion, they agreed with him: the gift was meant to bring him back.

Aunty Lynn Cook is standing nearby working on a single leaf of dried hala that Aunty Maile Andrade has given her. Aunty Lynn is in the process of carefully cleaning, softening, and rolling it up. ‘Anakala Eddie notices and takes a second leaf from her, saying, "‘O kēia ko‘u hana i ko‘u wā li‘ili‘i." This was my job when I was small. He opens the leaf, reaches into his pocket for a handkerchief, and then demonstrates how to do the work quickly and efficiently. "You dampen the cloth and rub this way. As you rub and pull, the leaf flattens out and gets a good cleaning. My grandfather used to have a little machine with a hand crank. We’d feed the leaf into the roll, crank the handle, and wind up the leaf into a roll. That’s what we called ‘owili lauhala." In the meantime, he’s finished cleaning his leaf and gives it, neatly coiled, to Aunty Lynn. She stands there in awe, rubbing the end of his lauhala between her thumb and forefinger. "He did in a minute or two what I’ve been working on for the last ten."

October 22, 2000 – Talk-story in the Dorms

‘Anakala quietly shares with us the contents of the ho‘okupu given to him by the New Caledonia chiefs and elders at Noumea Airport. Fabric, cigarettes, matches, food, chewing tobacco. All he says, with regard to the tobacco, is "I don’t have to smoke this, you know, for it to have meaning." Again, without really saying anything directly, he makes the point that paka should also have been part of our delegation’s gift to the Kanaks. What sense is there in withholding from them something that they have given us?

‘Anakala also tells the story of his afternoon visit to town. He comes upon a store with a beer promotion, talks to a good-looking clerk about the display, and learns that with the purchase of a case of beer, he can select one of three gifts: a t-shirt, a tank top, or a fanny pack. As might be expected, ‘Anakala manages in short order to charm the woman into giving him a free shirt. He then explains two concerns that came to mind: First, how to walk out of the store with the gift and not be "locked up" by the store’s security guards for shoplifting, and second, the inappropriateness of a beer-ad shirt to our delegation’s upright character. He says that he solved the first by clearing it with the clerk and the second by packing it away at the bottom of his suitcase. He then concludes his little story by telling us to be careful, to avoid doing anything that will get us locked up, and to make appropriate choices. This is a typical ‘Anakala Eddie story. You never quite know, when he starts, where he is going to take you, but learn to trust that he’ll get you somewhere worthwhile. This, we decide, is a very Hawaiian method of oratory and instruction. If you aren’t a Hawaiian listener (patient, attentive, trusting of your ho‘okele), you’ll easily miss the whole journey.

October 23, 2000 – More Dokamo Conversations

I heard from my sister Kahi that ‘Anakala gave a scolding today, his first on the trip. There are four advanced Hawaiian language students in the delegation who are taking the same newspaper-translation class at UH Mānoa. They were having trouble with a tough passage today from Ka Moolelo o Hiiakaikapoliopele, so they took it to ‘Anakala for help. He read it through, explained that he needed some time to get the context of the section by reading around it, but he grew frustrated when one of the four kept pressing him about "what this part here means." He then explained that kūpuna weren’t experts in all areas of the culture and that it was awkward for him to be asked about newspaper translating when his knowledge relates to Miloli‘i upbringing. Kahi, who was in the group, says that when he used the word nīele, they all drew back in embarrassment, having realized that they’d gone too far in their questioning—all except for one thick-skulled guy who remained oblivious to the subtle reprimand.

Later this morning, at breakfast, Mom told ‘Anakale Eddie that I was becoming pili to ‘Anakē Pine (Josephine "Pine" Kelley from Ni‘ihau), and that ‘Anakē had really taken to me when she heard me sing and play slack key. ‘Anakala then gave me some careful instructions: "When you’re with Pine, don’t nīele, don’t ask her all kinds of picky questions. Just ask her, ʻʻAnakē, pehea kou mana‘o—what is your thinking about this thing we’re looking at?’ Then let her talk. And if she talks too fast for you to understand, then ask her politely to ‘ōlelo hou because you haven’t made pa‘a her words." It is obvious to me, having just heard Kahi’s story, that ‘Anakala is speaking from immediate experience. He doesn’t want me to repeat the earlier gaffe.

At breakfast, ‘Anakala also describes the cracker and cocoa breakfasts of his youth. He would butter his palena and hakihaki (break) it into his pola koko (cocoa bowl). Then he’d eat this "cereal" with a spoon. "Ma muli o ka wela o ka wai, ua lana ka waiū paka ma ka ‘ili o ke koko a ua melemele akula ia, a ‘o ia ka ‘ono loa." Because of the heat of the liquid, the butter floated on the surface of the cocoa and turned it yellow, and this tasted so good. When they had really tough crackers (they called them "jailhouse crackers"—hardtack), they’d boil them first in a pot of water to soften them up a bit.

October 24, 2000 – Blessing of our Hale Hawai‘i at the Festival Village

While we wait at the hotel until it’s time to walk to the Festival Village, ‘Anakala explains to Dad that he ties his kīhei on the right side whenever he feels the weight of responsibility for the ceremony in which he’s involved. Because he has to cut the piko of our hale at today’s blessing (a very serious responsibility), he asked Tony Lenchanko, his dresser, for a right-side tie. "The tie calls my kūpuna to help me. I am not a graduate teacher of any kind. The knowledge I have comes only from my kūpuna, so the tie brings them to me."

At the hotel, ‘Anakala Eddie also explains to my dad the kukui-bark dyeing process that he learned from his kūpuna. The best bark is taken from down low on old trees. Take only narrow strips from the tree—not the whole circumference of the trunk, or the tree will suffer. Pound these strips into a pulp and add salt water. Then soak your items in this solution. ‘Anakala’s family usually did its pounding on the smooth pāhoehoe flats next to the ocean; careful pounding resulted in deep, cup-shaped depressions in the lava that were used over and over again. While pounding, he was instructed to move his wooden-log pestle in a circular fashion around the hole so that the sides would take on an even, circular shape rather than an oblong one. His people dyed their cotton-cord fishnets in kukui and salt water. The dye made the nets less visible in the water and made them more resistant to rot and wear. ‘Anakala also dyed his malo in this solution—the fresher the dye (and better the bark), the more dark red-brown the result. Dye was often poured into the bottom end of a beached canoe, and the nets were dyed there. Dye was also stored in metal tubs and used by all the villagers—not hogged by the family who made it. When the dye lost its strength, it was poured out and a new batch was made. Nets, according to ‘Anakala, had to be re-dyed whenever they started to fade. The malo, he says, was something his kūpuna had him hume (gird on) for certain ceremonies. He doesn’t explain what these were, but it’s clear than his malo was not for everyday wear.

At the hale blessing, we dance on the cement and mud in your ‘ōlena-yellow pā‘ū and tops. Dad tells me later that so many people come running to watch the ceremony that he is forced to crouch down at one corner of the house and take pictures through their legs. His best view of "Ke Welina," he says, is of yellow skirts reflected in muddy puddles. The color combination suddenly rings a bell for him: yellow butter floating in a bowl of cocoa. He compliments us with a variation of ‘Anakala’s earlier description: "‘O ka melemele, ‘o ia ka ‘ono."

When Mom and Dad return to the hale after lunch, Dad notices that it is beginning to look like an end-of-the-day crafters booth at Kapi‘olani Park. The ground is littered with empty water bottles and food wrappers. The display tables hold more personal items (bags, cameras, zippo lighters, bananas) than craft items. And most of the people lounging on chairs and leaning on the sills are simply there to eat or get in out of the rain. Worst of all, the laua‘e (of Makana, no less) with which we decorated the hale at the blessing, is now either snapped and dangling or trampled in the mud. So, too, with bits of the piko that ‘Anakala had originally cut with his ko‘i. "Not much pride-in-culture going on here," Dad mumbles.

After the long wait to give our gifts in the ceremonial area at the front of the main stage, Mom and Dad return again to check-up on the hale. By now, our crafters have packed-up and left, the Ni‘ihau ‘ohana has occupied a table and chairs to mālama their foot-weary kūpuna, and the rest of the space is occupied by non-delegation stragglers and leaners. Dad finds a trash bag. He and Mom clean up. Then they gather all the laua‘e and piko-remains in a separate bag and take this back to Dokamo with them.

Back at the bus stop, ‘Anakala Eddie notices Dad’s bag of muddy greens and he asks, with obvious relief, "Na ‘olua i mālama?" It was you two who took care of things? Dad nods and says, "This wasn’t meant to be ‘ōpala. It’s not rubbish." This, I think, is when ‘Anakala really gets close to Mom and Dad.

October 25, 2000 – Depart for Poindimie in Province Nord

Half the delegation is going to Province Nord where several dance performances and ceremonial exchanges have been scheduled for us in the rural villages of Kone, Poindimie, and Ponerihouen. The hula people and ‘ohana Ni‘ihau are in the traveling group; the crafts, art, literature, and video-media people are staying in Noumea to meet their Festival Village commitments. ‘Anakala Eddie explains to Dad that he might not be coming with us on our five-day visit. His reasons are difficult for Dad to understand, so Dad asks him to explain again in English. ‘Anakala says that he is not ready to leave our hale. He doesn’t think it right to bless the hale one day and leave it the next. Someone must stay with it for at least a little bit longer. Since Ni‘ihau is going north, he’ll be the one to stay behind. If Pine folks had decided to stay in Noumea, then he could come with us. Behind this delicately phrased explanation is, Dad thinks, a view of the delegation’s need for pono—for balance and harmony—and for the careful deployment of our spiritual leaders.

Since the ‘ohana Ni‘ihau is going north with us, ‘Anakala Eddie bids us a very tearful aloha as we board our bus. It is obvious that he wants badly to accompany us, but it is also clear that he is not a man to make selfish decisions.

October 26, 2000 – Ponerihouen

Today we take an hour-long bus ride from our dorm at Poindimie to a reception point at the beach in Ponerihouen. We share the crushed coral "stage" with the delegation from Papua New Guinea. They perform, we dance hula kahiko, and then we all take a break for lunch. During the break, a car pulls up with ‘Anakē Kahulu and ‘Anakala Eddie inside! ‘Anakala tells my dad, while we female dancers are changing into our tan mu‘umu‘u, that he now feels good enough about our hale in Noumea to leave it in the artisan’s hands. He says that on Wednesday, he took his pono lawai‘a to the hale, shared his mana‘o with everyone, and arrived at a happy balance of land and sea. He explains that when we blessed the hale, we gave gifts from the land: fern, vegetable foods, and hula. On Wednesday (the day we came north), he offered his gifts from the sea. Now the process is complete and the hale is whole.

I know that there is more to the story than ‘Anakala is willing to share. Stuff relating to what my dad calls the discord between our delegation’s po‘e ‘ai noa and po‘e ‘ai kapu, between the free and restricted "eaters." ‘Anakala is too diplomatic to divulge any details of his extra day at Noumea other than to say that we are all residents of a house whose land-sea balance has been restored.

October 27, 2000 – Poindimie

‘Anakala tells me and Dad about fishing for ‘akule when he was a boy. The kilo i‘a (fish spotter) would track the school as it approached two ko‘a (fishing spots) in the ocean off Miloli‘i—at places known as Kalihi and Kalanihale. At that point, the school would turn and move into a nearby bay with a sandy shoreline (I missed the name). There, two canoes were loaded with the joined nets of every family in the village. Everyone—the people on shore and those in the canoes—waited for the kilo i‘a’s signal to surround the school. ‘Anakala says that there would sometimes be grumbling by those on the shore below the fish spotter because the school would come right into the bay and be very catchable—but still no signal. Then the elders would scold the grumblers—"It is not your place to question him." Finally, the spotter would raise his bamboo signal pole (get ready) and then lower it (go!). The two canoes would head out to the middle of the bay, break off one to each side, drop the net, and surround the school. When the canoes went out, the fish didn’t move away. They stayed put. That was what the kilo i‘a was waiting for: the time when the fish wouldn’t move away at the approach of the canoes.

How the kilo i‘a knew this was the magic of his expertise. He waited to give the signal until he was sure. Because the school stayed put, more fish were caught; hardly any escaped. As the net was tightened, sections were removed and assembled into a second long net that was dropped outside the first. This kept the kaku (barracuda) and other predator-fish from hitting the inside net in their frenzy to get at the ‘akule. The net, ‘Anakala explains, was kept in place for three days. On day one, the village families were allowed to take the fish they needed. On day two, the fish sellers arrived with their trucks loaded with block ice to take a portion of the catch to the market. And on the third day, the remaining fish were released. Today, he says, a school that size would be completely wiped out by unscrupulous fishermen. They’d net it and take everything.

I get the feeling that ‘Anakala is telling us more than an old fishing story, but he leaves the hidden message, the kaona, for us to chew over on our own.

Mom joins us at the end of the story, and ‘Anakala asks her, "He hana ko ‘olua?" Do you (and Dad) have work to do? But Mom says no, she just came to listen. Dad remembers and repeats an old phrase that ‘Anakala has used on the "Ka Leo Hawai‘i" radio talk-show—"Nanea wale i ke kolekole ‘ana"—and ‘Anakala’s face lights up with laughter. He explains to Mom that kole, besides referring to the reef fish of the same name, also means "to shoot the breeze—to laugh, joke, and tell stories." In the old days, if you were talking like this and someone asked what you were doing, you’d say something like, "We’re just enjoying the kolekole-ing." If they came back later and you were still at it, they’d say something like, "Wow, the kole must really be biting." ‘Anakala then explains that different words are used to describe the different levels of intensity that a conversation can have. Kolekole and wala‘au are words for shooting the breeze; kama‘ilio applies to more important conversation; and ‘ōlelo is used for the serious business of giving instructions and arranging details. When a family meets to organize a big party, for example, they engage in ‘ōlelo; they are asked to take on certain responsibilities and each must listen carefully and respond appropriately; there can be no mixed or missed signals.

At Poindimie, after our two-hour performance, we have time to visit the craft booths and the ceremonial hale that the Kanaks have built for the visiting delegations. ‘Anakala and my dad meet for a while in this hale and then bump into each other again when they leave. ‘Anakala says that they were both wrong to enter the house through the back door and leave through the front. That’s backwards. If this were Aotearoa, the Māori would be very insulted. "When we come back to carve the pou (housepost)," he says, "we have to be sure to enter and leave in the correct manner."

Earlier this morning, ‘Anakala asks my dad for five delegation t-shirts to give as personal gifts to various people who have gone out of their way to aloha him. 1) to Mauri Maihuri’s mother who gave ‘Anakala a pāpale lauhala that she made; 2) to Mauri himself (Mauri is one of our liaisons; he is a New Caledonia-raised Tahitian); 3) to Manu, our liaison from the Loyalty Islands, 4) to Fred, our main driver and translator, and 5) to Pascual, our number-two driver. ‘Anakala also wants Dad to explain to everyone that he is wearing his new lauhala hat in honor of Mauri’s mother. He hasn’t bought a pāpale to replace his much-loved Mexican hat; he is wearing a gift to honor the giver. He also tells Dad that he would give his own delegation t-shirt away, but it is already worn (in Hawaiian custom, you don’t wear someone else’s clothes). Luckily, Dad has a new, black "Eia Hawai‘i" t-shirt in his bag, so this will go to Mauri’s mom. The other recipients, though, will have to wait until our Noumea return where, we hope, some unsold and ungiven delegation shirts will be waiting for us.

We return to the Poindimie festival grounds later in the day, and ‘Anakala spends a long time watching the pou-carving demonstrations that take place in the shade of a large tree. Pou is Hawaiian for "post"; the Kanaks build their traditional houses around a very tall, carefully carved, central pou, and we have been invited, along with the Papua New Guinea and Sāmoa delegations, to carve a section of the pou of the already-built ceremonial house. ‘Anakala, however, is not inspired by what he sees under the tree. He notes that the Kanak carvers are following a modern process that begins with a chainsaw-wielder who roughs out the basic shapes, followed by what seem to be apprentice chiselers who deepen and round out the chainsaw’s lines, followed by what appear to be more-accomplished carvers who supply the finishing touches. Although ‘Anakala doesn’t say much more than, "They use chainsaws and steel, not the tools of old," it is clear that he wants me to think hard about the assembly-line atmosphere and the apparent lack of spirituality. We leave, and he does not mention the pou-carving invitation again.

October 28, 2000 – Saturday and Sunday in Poindimie

‘Anakala returns early to Noumea because he has promised Haili‘ōpua’s group that he will attend their opening performance of Mauiakalana. Consequently, he misses our extra Saturday evening program (offered at the request of the mayor and chiefs of the district) and our Sunday farewells at the festival grounds and the school cafeteria. Later, when we tell him about the hour-long, house-building dance shared with us by the Kanaks of Poindimie, he seems both pleased and relieved, especially when we emphasize the sincerity and authenticity of this gift. The meaning of their dance—of building a house and inviting us to be part of its family—makes an especially big impression on ‘Anakala. He says that this is more evidence of our shared beliefs and common ancestry. Kanak and Kanaka, he says, were once the same.

October 30, 2000 – Return to Noumea

‘Anakala greets us with tears when we arrive at Dokamo. He tells us that he has asked our Noumea contingent to hold off on questions and story-swapping until we can get settled and rested. Then we can all sit together and share our separate mo‘olelo—theirs from Noumea and ours from Poindimie. He doesn’t think that it is a good idea for us to fire haphazard questions back and forth before that time comes. This again reflects the consistency of his belief in "all things in their proper place; all things in their proper time." It reflects, as well, his desire to avoid nīele (inappropriately curious) exchanges, not only because nīele is rude in itself, but also because it is an ineffective means of conveying information. It is better for everyone to hear everything at one time than it is to trade off bits and pieces here and there.

October 31, 2000 – A Visit to the Tjibaou Cultural Center

‘Anakala Eddie tells us about his visit to the Tjibaou Cultural Center with the Noumea contingent of our delegation—those who didn’t go north. He says that our liaison Eric Gaue wanted to take the group to the culture center kauhale (building complex) by way of a long, carefully designed pathway called the "Walk of the Ancestors." But the rest of the group chose to take the more direct route that simply led from the parking lot to the reception hall. They said they would meet-up with Eric later, inside. ‘Anakala, however, stayed with Eric and asked to take the long walk. ‘Anakala sensed the importance of that approach—both to Eric as a Kanak and to Eric as our host. ‘Anakala says he began their walk with an oli that explained who he was, where he was from, and why he was there. He did this, he says, to take care of things for the rest of our delegation. He offers no criticism of what sounds to me like "tourist" behavior. He simply accepts the responsibility of clearing the way, and I wonder how many other times he’s done this for all of us—north and south: quietly taking care of kūpuna issues that we aren’t even aware of.

November 1, 2000 – Performances at the Village and Secretariat of the Pacific

At breakfast, Dad tells ‘Anakala about Liko Hoe’s comment at yesterday’s performance. Liko was at the village early, watched the rain make its way there from high in the surrounding hills, and said to himself, "Ah, our hula family must be on its way here too." ‘Anakala says: "Yes, the rain has blessed us at each of our arrivals here. It rained when we dedicated the hale. It rained when we were greeted at Poindimie. It rained when we danced at Ponerihouen. And it has rained at our return performance at Noumea." He sees this, he says, as a hō‘ailona (sign) of our kūpuna’s approval; they make everything clean for us. They prepare the way for us to dance. He says that he’s talked to the Ni‘ihau family about it. He says that they see it in a similar manner: as signs, they say, of God’s blessing on us. He also mentions a makani kau wili (water spout) that he and the ‘ohana Ni‘ihau observed on the bus ride to our performance yesterday. It was a small one that rose in the waters off the village and moved slowly across the horizon. ‘Anakala says it was a pulumi (broom) that swept the path clear for us. I was looking out the same bus window that he was, but I missed the whole thing.

November 2, 2000 – Pōhaku from Tahiti

‘Anakala takes Dad on the side again to check on the white delegation t-shirts for ‘Anakala’s helpers. Dad tells him that only small and medium t-shirts are left (not the right sizes for anyone but Manu), but ‘Anakala asks for them anyway, regardless of size. He explains that he wants these to be given quietly to the helpers in his name and in the name of his kūpuna. Please, he says, no fanfare. ‘Anakala also explains that he didn’t bring this request up at this morning’s meeting (when Uncle Kalani reviewed our plans for tomorrow’s group thank-you to our hosts and drivers): "Kalani has enough on his mind, and this is a personal request." Dad is feeling pretty good; he is honored that ‘Anakala trusts him to take care of assignments of this sort. It’s a reward, I guess, for being patient and attentive.

‘Anakala takes us aside that evening to show us the carved pōhaku that he received from the master carver of the Tahiti delegation. ‘Anakala says that he’s been visiting the hale Tahiti off and on during our stay. His particular interest was in the large drum being carved by their main man in honor of all the delegations at the festival. At one point, ‘Anakala Eddie caught the man’s eye; they met, talked mostly in sign-language, and worked out the design for the Hawai‘i section of the drum. ‘Anakala says that the carver kept asking him, "Hawai‘i, where?" So ‘Anakala made a triangle with his thumbs and index fingers, tapped his fingers together at the apex, and answered, "Hawai‘i, here." ‘Anakala says that the carver got excited "and took it from there."

On his next-to-last visit to hale Tahiti, ‘Anakala’s new friend gave him a carved stone as a parting gift. ‘Anakala says that was worried about how to get the pōhaku home in his baggage, but he couldn’t refuse the gift. After he took it back to Nu‘umealani (our hale), he started wondering about its meaning. On one side he saw a face; on the other side he saw a pair of deeply incised parallel lines. After much thought, he began to interpret these lines as the root or foundation from which things grow and on which things are built. He had a chance to try out his interpretation (face and source: people thrive when they have a strong foundation) on a Tahitian who was visiting our hale, but the man only laughed and wouldn’t commit to an explanation. ‘Anakala was now sure that he could not take the pōhaku home without knowing its meaning. So he decided to return to "Tahiti" where, after waiting humbly in line, he caught the carver’s eye and communicated his desire to understand.

The carver, with hand-signs and help from English-speaking friends, explained to ‘Anakala that the incised lines form a penis and that that "face" on the other side is the equivalent female part. The meaning of the stone, ‘Anakala chuckles, is "ho‘oulu lāhui" (increase the population of our people). ‘Anakala chuckles even more when he explains that the answer was verified when he walked back from "Tahiti," crossed over to the stage where we were performing, and sat down to watch us do "Pūnana ka Manu," the mele ma‘i whose meaning is the same as the stone’s. He ends his story with the request that Dad remember it and share it with our hālau. I think he wants us to be the stone’s keepers when we return to Hawai‘i.

November 3, 2000 – Last Day

Before breakfast, ‘Anakala takes us to the traditional Kanak hale outside the Dokamo cafeteria and tells us that it reminds him of a hale at an O‘ahu heiau that he helped to reconstruct. He explains a little about the center posts of these houses: "Always you do something [leave an offering of fish, for example] before you put the pole in the ground. The spirit of land comes up through that pole and spreads throughout the house. That’s why certain lashings [at the top, I think] can’t be knotted. The knots will choke off the land spirit." Then he digresses a bit to describe the nīele behavior of someone at the heiau project who tried to interview him while he was at work. ‘Anakala says he completely ignored the man who, instead of taking the hint, now wanted to know why ‘Anakala was behaving so rudely. ‘Anakala explained to him that it was not the time for questions; it was time for important work. If he were to answer questions, it would have to be outside the heiau on non-consecrated ground, and he would have to know his questioner’s background and purpose.

‘Anakala’s little story sounds like it’s meant as a vote of encouragement and support for Mom; she has had trouble with several people on this trip who don’t seem to understand the focused, important work of hula. Their questions, interruptions, and complaints about exclusion make them very much like ‘Anakala’s nīele questioner. Mom is here to do hula—and hula, for Mom, is always a sacred activity in the sense that it requires the best of us. Not just on stage at the 8th Festival, but all the way here and all the way back home. It demands concentration, focus, and consistently responsible behavior. We dancers, she says, are all on a direct course to a clearly defined destination. We’re familiar with this mind-set. She expects it of us all the time, whether we’re going to Merrie Monarch or Moanalua Gardens. We know our roles on this trip, but others keep trying to jump in and out—cocktail glasses and shopping bags in hand—as if we were on a tour bus instead of a voyaging canoe.

November 5, 2000 – Te Tira Hou Marae in Panmure, Auckland, Aotearoa

A very disturbed ‘Anakala Eddie beckons to Dad before dinner, leads Dad to his mattress, and asks him to sit down. "I’ve lost my money belt," he says. "I took it off before showering, zipped it into my carry-on suitcase, and now it’s gone." Dad and ‘Anakala search through his bedding and the surrounding area, but come up with nothing. In the process, ‘Anakala confirms that he still has his passport, plane ticket, and spending money. All that’s really in the belt are his traveler’s checks. "I’m okay," he decides. "Let’s not make a big thing out of this. Don’t tell Kalani or Māpuana. We’ll wait and see if it turns up."

An hour or so later, an obviously relieved ‘Anakala goes up to Dad and laughingly tells him the story of how he just came back from the bathroom where, while adjusting his pants, he discovered that he’d been wearing his money belt all the time. The pouch had simply moved from front to back, so when he felt for it earlier, it wasn’t there. "So you see," he says, "I didn’t find it until I went to ho‘opaupilikia and took off my pants. I think my kūpuna were telling me, ‘You’re full of crap, old man. Don’t jump to conclusions; go carefully.’"

Despite his money-belt laughter, ‘Anakala has been unusually quiet and withdrawn for much of our two-day stay in Auckland. I learn later from my sister Kahi that it’s because he has learned that the pākeha (haole) have cut down the tree on Auckland’s One Tree Hill. I don’t know the tree’s story, but Kahi explains that it had great significance to the Māori of this land and that, when she was here a year ago with ‘Anakala and Ka Ua Tuahine o Mānoa, the Māori were chaining themselves to the tree in order to keep it from being felled. Now it is gone, and ‘Anakala (who has demonstrated throughout the trip a deep love for trees, house poles, and symbols of nature-as-shelter) is now faced with the loss of yet another connection between ancestors and earth. I wonder about the "Mother Nature" painting that we bought for him. I talk with Dad about it, and he says we’ll give the painting to ‘Anakala after we get home—when we’ve all had a chance to think through the many lessons of our trip.

December 22, 2000 – 8th Festival Reunion Party, Kailua Beach Park

‘Anakala makes it a point, early in the day, to sit with my family and thank us for "Mother Nature." Dad had given it to him a week earlier—quietly and without fanfare—when ‘Anakala stopped at the hālau to give us, in the same quiet way, the pōhaku that we have named "Ho‘oulu Lāhui."

In a rare moment of "direct talk," ‘Anakala explains that his purpose on the trip was to keep his eyes open and watch out for everyone in the delegation. His job was to keep us in proper balance: to hang his net from the sea in our land-heavy hale, to stay behind for a day when we went north, to read that signs that told of his kūpuna’s approval and of his kūpuna’s concern.

A group of dancers now gathers around ‘Anakala. Drawn there by his now-familiar talk-story posture, we’re perfectly willing to let him start and end wherever and whenever he sees fit. He launches into a retelling of how he received "Ho‘oulu Lāhui" from Tahiti’s master carver. As we listen, Dad and I exchange several knowing glances. Every detail of ‘Anakala’s story is exactly as he first told it in Noumea. This shows me yet again the kind of man he is. A man of his word, a man who does not exaggerate, a man with an amazing memory. It shows me, too, that the trip has met with the approval of his kūpuna. If I’ve learned anything from him at all, it is that his choice of story is never an accident. Long live our lāhui; may it grow and thrive.

Aia i Noumea Kou Pāpale Lauhala

na Kapalai‘ula de Silva

Aia i Noumea kou pāpale lauhala

Ulana ‘ia maila na ke Kanaky

Pumehana wale ho‘i ia ‘āina

I ka lawe ha‘aheo a Poindimie

Welo ha‘aheo kou hae kalaunu

Ho‘opulu ‘ia e ka ua lanipili

Hia‘ai ka mana‘o e ‘ike aku

Ua hana ‘ia ka pono, a pololei

Ualei pono ‘ia iho ka ‘upena

I pa‘a me ka leo a nā kūpuna

Ha‘ina kou wehi e ku‘u lei

No ‘Anakala Eddie lā he inoa.

ʻAnakala Eddie Kaʻanana presides over the blessing of Nuʻumealani, the hale Hawaiʻi at the 8th Festival of Pacific Arts in Noumea, New Calendonia. To his right is Māmā Kaleipua Pahulehua of Niʻihau.

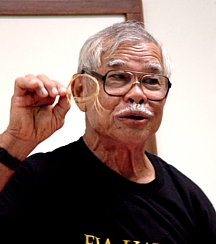

ʻAnakala Eddie and author Kapalaiʻula de Silva.

Haliʻimaile Shintani and Eddie Kaʻanana enjoy a Kanaka dance performance—pilou—at Ponerihouen, New Caledonia.

The day-long cultural exchange ends with the planting of pine trees. Pictured here are ʻAnakala Eddie and Mauri Maihuri, a New Caledonian cultural liaison for the Hawaiʻi delegation.

Kupuna Elizabeth Kauahipaula and ʻAnakala Eddie Kaʻanana lead the Hawaiʻi delegation in the 8th Festival of Arts parade of nations.

ʻAnakala Eddie (far right) and members of the Hawaiʻi delegation visit the Gavala Aboriginal Arts Centre in Sydney’s Darling Harbor.

ʻAnakala Eddie demonstrates sennit-making at a native crafts workshop.

The children of Poindimie, New Caledonia, gather around ʻAnakala in delight. They spoke French, he spoke Hawaiian, but the communication was instant.

Hoʻoulu Lāhui—the female side of the stone image given to ʻAnakala by the master carver of Tahiti’s delegation.