Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Camille Naluai [Ka‘iwakīloumoku]

On September 28, 2005, Fred Cachola received the prestigious Order of Ke Ali‘i Pauahi Award. This award is considered to be the highest and most distinguished award given to those who have exemplified the vision of Kamehameha Schools’ founder, Bernice Pauahi Bishop. In July of 2004, Camille Naluai had the pleasure of interviewing Mr. Cachola and discussing some of his numerous accomplishments and laughing over his well-chosen anecdotes. Ka‘iwakīloumoku has decided to republish this interview in recognition of Mr. Cachola’s lifetime of service to the Hawaiian community.

Lele o Kohala me he lupe la. Kohala soars as a kite.

An expression of admiration for Kohala, a district that has often been a leader in doing good work.

(Kawena Pukui, ‘Ōlelo No‘eau 1988)

The first thing you should know about Fred Cachola is that his heart is in Kohala. He is a self-described "kua‘āina kid" and thoughts of visiting his one hānau are always on his mind. Mr. Cachola grew up in a time when the very fabric of what it meant to be a Hawaiian was constantly challenged.

In the 1960s, Mr. Cachola became the first Native Hawaiian principal Nānākuli had seen for 30 years. Later he managed Kamehameha Schools’ extension education program—a program aimed at helping more Native Hawaiians outside of KS’s walls. He has gone where the road has led him. Guided by others, he now acknowledges his debt to the three most important people that have ever touched his life.

CN: You grew up in Kohala, right?

FC: Born and raised. Kohala had this weird kind of designation. It’s the only place, that I know of, where the Hawaiians called it "going in" or "going out." Kohala is a peninsula, so if you were going toward the windward side, like Makapala or Niuli‘i, it would be called "going in." If you were going toward Kapa‘au on the leeward side, then that was called "going out."

Now, most of the Hawaiians lived "in." Up in that area, there was Makapala, Niuli‘i, and Pololū Valley. Mary Lim (mother of the Lim Family of entertainers) and my mother were good friends. During the summers, my mother would send me to live with them. For me, it was quasi-camping, because they didn’t have indoor plumbing. That wasn’t unusual. There were a lot of places that didn’t have indoor plumbing. They had this one spigot outside and that was their source of water. Often, they would cook out in the shed. I remember, very vividly, Mary’s dad and his friends cooking taro in a 55 gallon drum, cut in half. Once a week they would cook it and then pound it with the poi pounders and make poi. Everyone around there would have poi.

My good friend was Mary’s oldest son. He would come over and stay with us, and I would go over and stay with them. One of his jobs was to clean the lo‘i (taro patch). He worked very hard. I had to go down to the gulch and help clean the lo‘i. That was the last time I really saw Hawaiian guys pounding poi the way they had for thousands of years. These guys were really good. You know how much taro can go into a big, big drum like that?

CN: I have no idea how much work that must be. You gotta have big muscles?

FC: Oh man, there was probably about a couple hundred pounds of taro, but they fed everybody. Everybody had taro. Coming to Kamehameha from a place like that was like culture shock. We had to wear shoes everyday. We had to learn how to put on a tie. We had a khaki uniform. It was quite a culture shock. You know, when I was at Kamehameha, I really had some doubts as to whether or not I wanted to stay there.

CN: Why’s that?

FC: Well, I was homesick. It was a strange new environment. I had never been away from home. I left home maybe once a year, just go to Hilo and go home. Never did I stay away from home. Just coming to Honolulu itself was a real shock. However, a couple of things happened during those first two weeks that changed it for me.

I’ll never forget the first music class I went to. As a kid growing up I always liked music, but they never had music in Hala‘ula Elementary. If they did, the kind of music we learned was "God Bless America," all American stuff. That’s what we were learning. "Oh Columbia the gem of the ocean," you know that kind of stuff? I don’t know if I ever sang a Hawaiian song. I never knew what a Hawaiian song was like until I came to Kamehemeha.

My first music class was in a common room at the ‘Iolani Dorm. I was with 25 guys I’d just met. I didn’t know who they were, and I wasn’t quite sure what their names were. We all wore uniforms. I was trying my best to keep up with the group, find out about the classes, where we were supposed to go next, what to do next, what time do we eat, what happens after lunch. You know, I was just a kua‘āina kid from Kohala, what’s going on?

Martha Hohu, Aunty Martha, was at the piano. This was in 1948, and she said to the class, "Welcome back boys. What do you folks want to sing?" One of the guys said, "Can we sing the Song Contest song?" Keep in mind, I didn’t know what Song Contest was all about.

At that time, there were 2 divisions, junior division and senior division. For the junior division, I think it was the 7th, 8th, and 9th grades competing against each other. Senior division was 10th, 11th, and 12th for boys and then there was another one for girls. The year before, when they were all in the 7th grade, they sang "Ahi Wela," and they won first place. So a year later they’re 8th graders, and I was with them. Mrs. Hohu said, "Let’s sing ʻAhi Wela.’"

I didn’t know what that meant. I didn’t know what it was all about, but I just sat there. She started playing and all of a sudden . . . these guys won song contest, so they were good. But this was just one class with 25 guys, so there was a total of 100 of us. They sang, and I almost fell off my chair! These guys were singing Hawaiian words. There was no music. They had it memorized. They were singing in harmony, they were singing in parts and I said, "I found heaven."

From that moment on, I wanted to learn all the songs they knew and to tell you the truth, I don’t think I’ve stopped singing since. I never had this at Hala‘ula Elementary. I was like, this is the kind of stuff I can get at Kamehameha and if there is more of it, I want to stick around. That helped.

There were interesting things at Kamehameha. The classes were fascinating. I had never had classes with different instructors. We usually had self-contained classes. You know, Mr. O’Connel was 5th grade, Mrs. Brown was 4th grade, and you stayed there all day. I’d never had such interesting people like Don Mitchell, Martha Hohu, and the band. I was like band, B-A-N-D, I can play an instrument! I was still homesick.

The second thing that changed my mind was, in those days, the mailboxes were right next to the old Pākī Office. It’s now Keōua Hall. All the boys’ mailboxes were outside. After lunch I came down and I saw this one box filled with letters. I thought, "Wow, that guy’s got a lot of mail. Oh boy, that’s close to my box." I walked up and it was my box and it was stuffed with all these letters.

I pulled them out, and there they were. I could just tell by all the addresses that they were all my old classmates. My classmates were writing letters to me. Each one of them. I ran up to my room and opened them up. They said something like this, "We’re so proud of you, wow! You’re the first one from our class to go to Kamehameha. You are going to do good." I felt like, "Geez how can I go home now? These guys are expecting great things out of me." I didn’t want to let them down.

Come to think of it, I might have been the second one from the school. My sister was probably the first. Those letters really helped me. I think the teacher at Hala‘ula knew what was going on and did that as a class assignment to kind of help me get over being homesick. That really was nice. I received things from my classmates that said, "Do good. We’re proud of you, you representing Kohala." That really stuck in my mind. You know, even now I feel proud to be from Kohala. I tell people I am from Kohala. It’s my home. It’s my ‘āina pono‘ī. I had that feeling when I came to Kamehameha, you’re a Kohala boy.

CN: But you stayed here?

FC: Well, I go back and forth as much as I can. I tell my daughters, "I hear the voices calling, I gotta go." We have some property in Kohala, and we are planning to build a home there and go back and forth. As youth, those who influenced us, teachers, parents, society as a whole, the plantation community, the community at Honolulu, at Kamehameha, were of the mindset that to be a good American you had to be a bad Hawaiian. That’s what the school was all about; "contributing citizen" meant you were going to be a contributing American citizen. To be a good contributing American citizen, you had to undo all the Hawaiian things that you may have brought with you. Our girls couldn’t do any hula. When we had talent shows, the President (of the school) had to hear what we sang before he allowed it to be put on the stage. If he didn’t like it, if Colonel Kent didn’t approve of it, we weren’t going to sing it.

CN: How did you wrestle with that, because obviously it bothers you? Did it bother you then?

FC: To me, it was all part of the military mentality. We were immersed in the thought "Don’t question, just do." The seniors were the leaders on the campus. The R.O.T.C. officers were the leaders. Every where you went you were reminded of some kind of hierarchy of authority. It wasn’t unusual for us to have to audition and to be closely controlled.

All things Hawaiian at the school were really underground. One of the best things that had any sense of Hawaiian identity was this club called Hui ‘Ōiwi. You were invited by Dr. Mitchell to join Hui ‘Ōiwi. It was something to be done after hours, extra curricular. I never got invited but some of my friends were. They learned Hawaiian games, food, and things. You know, Dr. Mitchell was a true Hawaiian at heart. I think deep inside he felt sad that this wasn’t being done at school. He was pushing the envelope, pushing the limits at the school.

We didn’t learn much Hawaiian at all. It wasn’t my fault. It wasn’t their fault. I think we were victims of society at that time. To be a good contributing American citizen, you could not be a good contributing Hawaiian Kanaka Maoli. We studied French for two years and it was a gas, because I came out of Kamehameha speaking good French and not one phrase of Hawaiian at all! If you listen to the speeches that were given at that time, not even an "Aloha Kākou" was heard. I am glad things have changed since then, and I feel like after I came back from college . . .

CN: Where did you go to college?

FC: I went to Lamoni Graceland College, a small junior college in Iowa for two years, then I transferred to Iowa State Teachers College. After coming out of Kamehameha in 1953, I thought I was well-prepared for college. I was in the college prep section. There was no question in my mind that that’s what I should do.

I don’t know who decided, but when we were in the eighth grade somebody decided that "25 of you will be college prep, 25 of you will be commercial, and 50 of you will be in the shops." We were tracked. Somebody gazed in a crystal ball or looked at our records and we were tracked. If you were in the college prep section, that’s what you did. You went to college. If you were in the commercial section you might go to a commercial school, business school. The rest were going to the electric shops, carpenter shops, welding. They didn’t get to decide. It really is sad. A lot of them probably could have gone to college just as easily as I did, perhaps better than I did.

Anyway, I knew that I was prepared to go to college. When I was eight years old, my mother left. I was half orphaned. We were very modest. We were a poor family and there were six of us. One of my sisters was hānai’d, so that left five of us. I’m trying to make a point about going to college, so hang on to that point.

As we were growing up, the Child Welfare Department was wondering whether this Cachola man could raise five kids. They were ready to split us up until the Lili‘uokalani Trust stepped in. I’ve always said that there were two ladies in my life that really did a lot for me. One was Bernice and the other was the Queen. The Queen paid all my bills, my plane fare, the barber shop when I got a hair cut. I just signed. When I went to the school store, I just signed. I had no worries. They even gave me a few bucks extra sometimes and flew me back and forth.

The school gave me a scholarship. Tuition was only $124. My father couldn’t afford that. The point is when I graduated, I knew that I couldn’t go to college—that there was no money and at that time there were no scholarships. No scholarships at all. So, I joined the army. About half of my class did. This was during the Korean War. A lot of Kamehameha alumni were going to war. While we were at school, we were having memorial services for young guys who were killed in battle. Kamehameha alumni, Don Ho’s younger brother Edward Ho, and Ennis, and there were some others who died in Korea.

When you graduated you were of that mindset, ready for going into the military. It wasn’t that big of a deal for us. It was almost natural. We were well-prepared for doing that. After five years of R.O.T.C. we were well-prepared. When I got into basic training I knew all about map reading. We could field strip the weapons blind folded and put them back together. That’s the kind of training we had up there.

I graduated in 1953 and went back to Kohala, and I wasn’t quite sure what I was going to do. I knew I couldn’t go to college but I applied anyway. I applied to the University of Hawai‘i and took the exam. It was so funny. The bus took us down to Hemmingway Hall, or some place on the University’s campus, and you could tell the Kamehameha guys because they were all wearing uniforms. There were a lot of other students from different schools. We all sat down in one group and started taking the exam. The first guy to leave was Andrew Poepoe, which didn’t surprise me. He was our valedictorian, smart bugga.

Anyway, a couple of our guys stood up; a couple more of our guys stood up; then a couple more guys stood up, and they were all from Kamehameha. I was like, "Geez, I better hurry up!" I took the exam for USC and I applied for Washington State, Oregon State, and Montana State because I wanted to go into forest management. They all had a good curriculum in forest management. I got accepted into all of them.

I knew I was smart enough to go to college, but I just didn’t have the money. I told my dad, "There are two ways we can go here. Let me join the army. I’m only 17 ½ years old, so you’re going to have to sign the papers. Then, lend me the car keys so I can drive to Hilo and sign up. I can make the military my career. I’m well-prepared for doing that. I can get a GI Bill and go to college. Those are good options." He said, "There’s a war going on, son, and I don’t want you to go." I said, "Dad it’s going to be over in a few months." He said, "It’s not over yet." I said, "What do you want me to do, sit up here and dig weeds in the cane field like all the kids from the high school are doing?"

My last job before I left was spraying herbicides. Who knows what I was breathing! My dad was very reluctant, but finally he agreed [to let me go]. So I went into the army. I took all the exams for Officer’s Training School. Passed them all, no problem, but I was too young. I wasn’t even 18. They kept me back as a cadre. There I was, an 18-year-old cadre at Schofield Barracks, preparing guys who were going to the Korean War. I was the youngest cadre in the army, I think.

But I began to get funny kinds of feelings. I looked at myself and thought, "Why am I doing this?" I was training people to be good killers. It kind of made me feel a little different. I told myself that I didn’t want to be a part of this. If I had to do it, I’d do it, but I didn’t want to continue this kind of thing for the rest of my life. When I was 19 they asked if I wanted to continue and I was said, "No!" I got my GI Bill and went to college.

The reason I ended up in Graceland, was that my older sister was a nurse on the mainland at that time. She married a local boy who was a missionary living up there. When I went to visit her for the Christmas holiday as part of military leave, he asked what I was planning on doing when I got out. I told him that I was probably going to college. He asked where I was going and I told him that I had been accepted at several places, and I was sure that they would accept me again. He asked if I had ever thought of Graceland and I told him no.

So, we went up to take a look at the school. It was right up the road from where they lived. It was a small little college in the middle of the corn fields with one main street in the town. I thought I could handle it. They were all church people. The corn fields looked like cane fields. They were all nice. They chewed chewing gum and popped popcorn. I knew it was very strict. No smoking, no dancing, no drinking, all that sort of stuff. That’s exactly what I needed. I was a real rambunctious 20-year-old army guy. I figured if I went home, I was going to blow it. I wanted to really get serious. I wanted to become a teacher. I enjoyed teaching in the army so I stayed at Graceland, and then I went to what I thought was the best teaching college in the Midwest, Iowa State Teachers College.

In 1960 when I came back home I really didn’t realize how much I had missed this place. I was wholly immersed in mid-America for so long. My family said, "You sound different, you look different." It was a joy to go back home to Kohala and see my friends and to see some of the old timers there who would come up to me and say, "Are you really a teacher?"

In my final year at college, people were signing up for contracts and I had several interviews in Iowa. At this one interview, they only saw three of us. It was a special section for teaching history and historiography. I was a history major and it was exactly what I wanted to do. I got the job because I was a veteran. It was for the big sum of $4,200 a year! We had a tradition in the dorms where every time someone would sign a contract they would put up your name, the place, and the amount. Everybody else was signing for $3,800 or $3,900. I had also applied for a job in Hawai‘i. The superintendent in Iowa at Davenport gave me three days to make up my mind. I swear my ‘aumakua was looking after me because on the third day, I was just about to mail my acceptance to Davenport when I saw in my mailbox the letter from Hawai‘i. It said they wanted me to teach in Hawai‘i but they didn’t know what I was going to teach or where I was going to teach. But they promised me a job and I would be paid $4,200.

There was no question in my mind, I was going home! I thought about how close I had come. Just one day. One 24-hour period really made my life. I could have gone to Iowa. I wanted to.

This happened in March and we didn’t graduate until June. In March I was guaranteed the job. All of April, May, June went by and not a word from Hawai‘i. I was writing them letters, asking them where was I going to teach, what was I going to teach . . .? I came home that summer, my sister picked me up from the airport and she asked what I planned on doing. I told her I was going to take a nap and then go down to the DOE.

I caught the bus, came into town, and went straight into the DOE office. The man there told me, "You know we made a big mistake; there are 400 of you that we shouldn’t have hired." I said, "Well my letter says I have a job." He says, "Yes, you do. Would you like to resign?" I looked at him and said, "I tell you what, will you send me back to Iowa?" He couldn’t, but he looked at my records and said, "You know what? Your records look pretty good. I don’t think we are going to have any problems with you. In a couple of days, you’re going to Wai‘anae Intermediate." That’s where I went.

All my friends said, "Wai‘anae? Man, you’re going to teach in Wai‘anae!" I said, "What the hell is wrong with it?" I stayed and lived there in Wai‘anae for 30 years. Teachers could hardly wait to get out and I just stayed because I knew those kids, I loved them, and I could teach them. It didn’t bother me to stay in Wai‘anae. I just moved to ‘Ewa about five years ago. My daughter grew up in Wai‘anae. Then I became the principal at Nānākuli. I was about 32 years old in the biggest school with the biggest problems. Nobody else wanted to go there.

But there was something else that happened in my life that really made a difference. You already know about the Queen Lili‘uokalani Trust. Mrs. Carter was my social worker from LT. Once a month she would drive up to the school and after lunch, during recess, I would go meet with her just to talk story. In my 9th grade year, the school office called me and said, "Fred, you have a new social worker who’s coming to meet you." I went up to the parking lot, I was standing there, and I see this guy sitting in his car. He comes out, he looks at me, and I look at him, and he says, "Are you Fred?" I say, "Yes, I am." He said, "Well Fred, I’m glad to meet you, my name is Pinky Thompson." I said, "Glad to meet you." We shook hands . . . you know he may have let go of my hand, but he never did let go of me.

Pinky stuck with me for the rest of my life. He followed me everywhere. He went to bat for me. My sophomore year we did something really stupid. We lived in Kaleiopapa Dorm and did a lot of recreation down in the valley everyday—from harvesting honey and mango to damming the stream to smoking cigarettes, all that kind of stuff. Eventually we just naturally drifted into alcohol. Our sophomore year we were drinking beer the afternoon before Song Contest. We were in pretty good spirits. We came back to the dorm and word got out that there were about two dozen of us drinking beer.

CN: Wow! That’s a lot of kids.

FC: Oh yeah, a big bunch of us. The supervisor knew that people were drunk. As I came out of the showers, I looked down the hall and there he was at my door and he told me, "Come here." He smelled me and said, "Get in my apartment." I opened his door and there were six guys in the apartment. Song Contest was like in an hour away and he looked at us and said, "Don’t you guys have solo parts?" We said, "Yeah, we do." He told us that if we didn’t sing, our class wasn’t going to win.

We were stupid and he said, "You know what? I gotta sober you guys up quick. Open your mouths." He got coffee grinds—raw coffee grinds—and he told us to chew, spit, and rinse. Than he got a tube of toothpaste and he went right down the line squirting that toothpaste into our mouths. He said, "Everybody chew on that; now everybody stand up walk around."

So what did all this tell us? We could do anything we wanted! Junior year, we did the same thing and this time we were all in his apartment again, all the same guys. With tears in his eyes he said, "You know? I should have done this last year." He picked up the phone and said, "Mr. Bailey will you please come to my apartment? I have a problem." We thought we had to pack. This time it was before junior prom. We had to give our leis to someone else, and we worked it all out with our dates and told everyone that there were six of us packing in our dorms.

But, ta dum ta ta! Pinky Thompson came to the charge and talked to Mr. Bailey. To make a long story short, none of us were kicked out and I know that Pinky helped to allow me to stay there. Of course, the next meeting I had with him he just bawled my head off. After I graduated he said, "I wish we could do more for you but we can’t. That’s it—you’re on your own, but good luck."

Anyway, I was teaching in Wai‘anae and I came back to the singles’ cottage; I was single at that time. All the guys were in a cottage and there he was, Pinky Thompson. I said, "Wow!" He said, "I heard you were here." I said, "Yeah I’m teaching." He said, "You know I think it’s time you start giving back. Would you mind sitting in on the advisory council of the trust?" I said, "No, of course." So I did, and I used to see him all the time because he was the director for LT—Lili‘uokalani Trust.

A couple of years passed, and I was principal at Nānāikapono, and I got a phone call from Pinky. Guess what he is now? He’s the Governor’s Aid; he’s Governor Burns’ top aid. He came to my office and said, "I’m very proud of you, you’re doing really well. There are a couple of things I want to ask you to do. There are a lot of Hawaiian guys going to Vietnam—they’re local boys and it’s breaking up a lot of families. They don’t want to listen to these guys. I want you to serve on that local draft board and begin listening to some of their hard stories."

I got on Local Board Number Five and I couldn’t believe it. They’re pleading their case and this one board member is snoring! Another board member is cleaning his fingernails and he told the guys, "What’s the matter, you not proud of your country?" It was really bad. Pinky got me on this local board, and I helped to turn things around for the kids.

Then Pinky came back and he said, "What do you want to do with this school, Fred?" I said, "What do you mean ‘what do I want to do’? This school has so many problems you don’t know where to begin!" He said, "Well, what would you like?" I said, "First thing we gotta do, Pinky, is clean up this place. The buildings are broken down, the curriculum is outmoded. Look, LOOK, the railings are broken, the buildings have never been painted . . ." he said, "Tomorrow morning some guys are going to come see you. I think they can help you."

Nine o’clock the next morning, do you know who was there? The head of the Department of Accounting and General Services—DAGS. They walked in there with their big blue suits and ties and they said, "Young man, we heard you have some problems over here and the place needs to be fixed up." I said, "Yeah! Absolutely!" So someone said, "Okay, let’s go take a look." I thought it was only those two guys, but when we left my office and he waved to the parking lot I saw about eight guys coming down with notepads in their hands.

People in Nānākuli couldn’t believe it. They thought I had the kind of mana that they had never seen. They knew it was useless to even ask. Things would never happen. Pinky Thompson made it happen, on my watch. You know what that meant? First part-Hawaiian principal there in 30 years—young, 32 years old, something good was going.

In 1971, I’m up there at Kamehameha and they told me the trustees had just approved the establishment of a new extension division. It was an outreach program to work with the kind of kids I was working with. So I decided "Wow, what a challenge." When I first started teaching in Wai‘anae I was teaching 32 kids—first 32 then later on 34. I mean, two of them were sitting on my desk! I couldn’t sit down because there was no more room. When I went to Kamehameha, all of a sudden my classroom became 40,000 part-Hawaiians.

So it was a bigger class, but then I was getting big money and a lot of help. I kept telling all the people who worked with me, "Don’t ever lose your teaching mentality ’cause if you do, you’ve lost it. You may be president of the school but if you can’t figure out what’s going on at 8 o’clock in the morning, if you don’t have that sense of teaching, you’re losing the mission of what education is all about."

I got to Kamehameha in ’71 and Pinky Thompson had been appointed as a trustee. I tell you, the ‘aumakuas. Now I can say this: he’s long gone and bless him, but we had a lot of private meetings, me and him. We’d sit down and we would talk. It was such a joy to me to know that there was at least one trustee who would support me when I would say, "We gotta work with pregnant women. We gotta work with dropouts, we gotta go to Ni‘ihau, and we gotta get preschool started."

We did that for 25 years. We took Kamehameha to a place where it would have never gone, and it was a joy. Pinky called me up one time and said, "Fred we’re going to have a trustee retreat and we’re going to ask three of you from the school to come down. We’re going to go out there and we’re going to create a mission statement." During the meeting Papa Lyman, the chairman, said, "You know, we talk, talk, talk, talk. Someone’s gotta start writing." He said, "Nancy, Pinky, Fred, Bob—we’re going for lunch. You guys stay here. We’re going to bring the food here. When we come back after lunch you guys are going write something."

That’s exactly what happened. Everybody left the room and four of us were there. They brought the lunch in and we started writing the first mission statement for the school. Pinky was right there. When you think about shaking hands with him, almost 30, 40 years before that and all the things that happened in your life . . .

CN: He played a part in all of that, didn’t he?

FC: Oh yeah! It’s crazy but it was wonderful. It was at that same meeting that I suggested, "By the way, I think the best use for some of our lands is education." The land manager turned to me and said, "I’m not going to show you one damn map." I turned to him and I said, "Do we work for the same company?" He said, "You guys just stay up there. We’ll make the money but you guys just stay up there."

Eventually Pinky was able to persuade them, because the land managers at that time didn’t want to have anything to do with the school. It was a joy when we got 10,000 sq. ft. in Kona, which was just a rubbish dump, nothing. It was the big eyesore of Hōnaunau, one of the most sacred places right across from Hale O Keawe. This was Kamehameha Schools Bishop Estate land. I said to Pinky, "We want to create a drop out school down there." He said, "Just stick with what you guys can manage."

This was an empty lot. Not leased to anybody; it was just 10,000 sq. ft. It was a rubbish pile. The land managers in Kona thought it was crazy to allow us to have it, and then I hired some guys that the police told me were on surveillance. I told them, "I know, but these are the guys that understand these kids." I told the police, if they do anything wrong, bust ’um.

Right in front of the Land Use Commission, I told them straight, "What we’re trying to do is what my ancestors had been doing for hundreds of years—and that’s make things right." Pinky used to say that all the time too, "Nānā i ke kumu, look to the source," because that’s where a lot of the answers are. We never did pay attention to that. Only now our land managers talking about ahupua‘a and the systemic affect. We’re now talking Hawaiian values, all that kind stuff. All these things started many years ago.

It was a joy to work with Kamehameha. The classroom of 40,000 was very manageable. The school has a lot of good people who can do that, Juvenna Chang, Neil Hannahs, people I worked with; people that I helped to mentor. They’re all still there and they know the spirit, they have the mana. I love to see the schools saying, "We gotta do more, we gotta get out!"

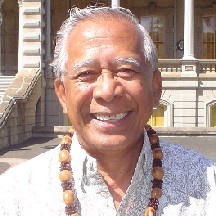

Fred Cachola in front of ‘Iolani Palace where he volunteers as a docent.

photo credit: Michael Young

The Kamehameha Men’s Alumni Glee Club performs with one of their distinguished members, Fred Cachola, pictured here second from right.

photo credit: Michael Young

Fred Cachola is a recipient of the 2005 Ke Ali‘i Pauahi medal. This prestigious award recognizes individuals who have made extraordinary lifetime contributions to the Hawaiian community and exemplify the values and vision of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop.