Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Hi‘ikua Pakaiea

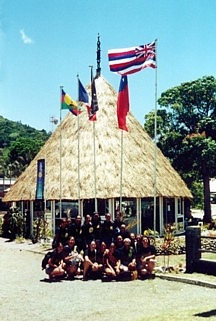

It is late, dark, and cold when our bus finally pulls into the gravel lot at the village of Poindimie, New Caledonia. Hundreds of native Kanaks have been waiting since early afternoon to welcome us to the land they call Kanaky. Their chiefs stand in a row facing us. Their gifts of cloth, tobacco, and paper money are laid out before them, and the flags of the four participating nations hang from poles behind them.

We take our place to the right of the Sāmoa and Papua New Guinea delegations. We take our turn, as well, in the exchange of oratory, dance, and gifts. One of our makana is a Hawaiian flag. "We mean no disrespect to the American flag," says our delegation leader, "but this Hawaiian flag is a truer symbol of the people we represent—both present and past, seen and unseen. It speaks of a struggle that we share with you. It speaks of loyalty and perseverance in the face of loss and change."

Several minutes later, in the middle of Sāmoa’s presentation, we quietly nudge each other in kākala-ka-‘ili surprise: E nānā, the American flagpole is coming down. The Kanaks are lowering it carefully into the crowd. Now it’s being raised again, but this time it’s Ka Hae Hawai‘i that unfurls in the night breeze. "Welo ana e ka hae Hawai‘i," Queen Emma’s 1874 campaign song, is suddenly pounding in my head, and we stand there in tears, shaking with emotion, as a heavy North Province rain begins to fall in blessing on the Kanak and Kānaka below.

My dad calls this an epiphany, a moment of intense personal clarity. All I know is that I am filled with pride: pride for the path that was chosen for me, pride for the path I am choosing for myself, pride for the fact that the two are actually a single, narrow path that leads to being Hawaiian.

My parents believe that it is difficult to be Hawaiian. They say: if we don’t work at it, we’ll soon become the mea ‘ē, the something else, that is created by T.V., Internet, cell phone, and shopping mall. Thus, when I was young, my parents allowed me no choice in matters Hawaiian. They set me on a narrow path: Hawaiian dance, literature, language, and music. I have never not been in hula. My bedtime stories were "Nā Kāma‘a o Keawe," "He Mau Pepeiao Ko Ka I‘a," "Nā Akua o Pānau." My first "novel" was Emerson’s Pele and Hi‘iaka. I was enrolled, as a four-year-old, in a Hawaiian language class of fifth grade whiz kids taught by two of my ‘Anakala: Louie Lopez and Kamaki Maunupau. My lullabies were "‘Āhia" and "Kananaka." My favorite singers were Johnny Almeida and Aunty Genoa, my first cassette, Eddie Kamae and the Sons of Hawai‘i. I can’t remember not being able to play the ‘ukulele.

As I grew older, my parents seemed to give me more freedom of choice—but, as I realized at Poindimie, they were actually training me, over and over, to choose to be Hawaiian. I was rewarded with smiles for choosing the wahi pana of Kailua as my 4th grade research project, for choosing to learn Hawaiian food preparation from my Grams, for choosing weekly visits with hula Aunties Lani Kalama and Sally Wood Naluai, and for choosing to tag along everywhere with ‘Anakala Louie Lopez, a man whose Hawaiian generosity knew no bounds.

I was rewarded with long, confidence-building talks for choosing the hula club over the basketball team in 7th and 8th grade, with nods of proud approval for choosing to take up slack key guitar in my 8th grade summer, with steady "you’ll just have to take it on the chin" assurances for choosing to stick out a 9th grade Honors English course that subtly trivialized the value of Hawaiian literature, and with pu‘uwai haokila support for my subsequent decision to decline a recommendation to enroll in 10th grade Honors English and to sign-up, instead, for an innovative, Hawaiian literature based, regular English 10 class taught by the most intense and impassioned of teachers, Richard Hamasaki.

I realized, beneath the flag at Poindimie, that the last two years have seen me through a quiet transition from koho ‘ia (that which is chosen for me) to koho (that which I actively choose). That which my parents chose for me—and later steered me into choosing—has become that which I confidently choose for myself. I have chosen to continue to dance, study Hawaiian language, pursue my interest in Hawaiian music, absorb as much of my culture as I can, and critically examine those who attempt to corrupt it. By my own choice, I accept responsibility for composing mele, perpetuating kī hō‘alu, and singing in my Hawaiian music quartet. By my own choice, I ignore the conventional wisdom that says that there will be a tragic void in my education if I do not attend a "mainland" college. Instead, I choose to enroll at UH Mānoa next year and study, with Hamasaki-like passion, music and Hawaiian language.

One thing more, something ironic, came to me in the rain at Poindimie: my newfound sense of koho leads me to a powerful, comforting sense of koho ‘ia. My free choice is to choose the path that has been chosen for me. This keiki finds that the two paths are one. This keiki, moreover, finds herself ready to take on the roll of makua: to make it harder for the next generation of Hawaiians to unchoose their path, to make it easier for them to be full-capacity Hawaiians and proud of it. Thus, in myself, I unfurl a century-out-of-date flag that speaks of loyalty and perseverance, of stubborn choice in the face of loss and change. Let it rain, I say, let it rain.

© Hi‘ikua Pakaiea 2001

photo credit: Kīhei de Silva

The Hawaiian flag flies over the traditional Kanak house constructed on the festival grounds of Poindimie Village in the North Province of New Caledonia.