Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

The following essay is from the Mary Kawena Pukui Collection

In the three Bishop Museum publications on feather work, nothing is mentioned of religion in connection with this art. The early Hawaiians did nothing without appealing to the gods. Fishing farming, canoe making, paddle carving, medicine and the treatment of the sick, house building, tapa making and printing, and so forth, all had gods and goddesses presiding over the work. Even dancing and skill in warfare were taught with prayers, and as feathers of birds were used to adorn the chiefs, who were believed to be related to the gods, the gathering of feathers and the use of them to fashion royal adornments were definitely based on religion. The persons of the chiefs were regarded as sacred, therefore, whatever they wore was kapu.

The wearing of cloaks and capes belonged exclusively to chiefs and priests of chiefly background, like Kahoaliʻi and his followers. Who says that, with all the kapus attached, they had nothing to do with religion?

When a bird catcher went to the upland to catch birds, he appealed to the Kūhulumanu or Kū‑of‑the‑feathers, thus:

O Kūhulumanu in the darkness of night,

Brush aside the darkness and come forth into the light,

This is I, So‑and‑so, appealing for mana,

Grant me wisdom and skill,

Grant me a good catch of birds,

Go up to the mountain top,

And drive them hither,

Let them find my gum and be held fast,

Amama, the prayer is freed.

Panaʻewa, Piʻihonua, and Hailikulamanu were well known bird catching places in Hilo. Most mentioned of bird catching places in our ancient chants was Laʻa, now known as ʻŌlaʻa.

Part of my childhood was spent in ʻŌlaʻa, at a place called Kapuʻeuhi by the ancients, and Glenwood, after the railroad track from Hilo ended there. A spot there was pointed out to me as once being the site of a bird catching shrine called Hoʻolelenālupe. I remember the numerous ʻiʻiwi, ʻapapane, ʻelepaio, ʻamakihi, and some ʻio. The only introduced birds there at the time were mynahs. When I returned to the same place forty years later, introduced trees were growing and the ʻiʻiwi had retreated deeper into the forest and were rarely seen.

It has been my good fortune to know some of the old time feather workers of the old category, most of whom had made them in the courts of our last rulers, such as Malulani Beckley Kāhea, Keahi Luahine Sylvester, Elizabeth Lahilahi Webb, James Lono McGuire (whose mother before him was also an expert in the art), Annie Reist, and Sarah Smythe. Of these, only the last named is living, the rest are gone on the unknown path of Kāne, where no one follows until he is called. All of these people were of royal descent, for no commoner was permitted to do feather work in the olden days. Feathers were used in royal standards, to adorn chiefs and chiefesses, and for images of the gods. No commoners were ever permitted to adorn themselves with feathers or with whale tooth ivory. As I understood from some of these beloved seniors mentioned above, prayers were always a must and designs were often revelations from the gods, to the person for whom the article was intended or to the head of the project. “This is the design that you must make for So‑and‑so, which means such and such,” therefore by this I know that designs are not meaningless things used only for decorations.

It was Malulani Kāhea who told Jane Winne that he was named for a kāhili belonging to Queen Emma. She, in turn, asked me whether we have a kāhili in the Museum. “Yes, we do.”

I remember seeing a cape made by him, following World War I, as a memorial to his brother who died while serving in the British Army. Their mother, Kahāʻawelani, was a direct descendant of Captain Beckley, an Englishman, and of the prominent chiefs of Kohala.

The cape was not made on olonā netting as the older ones were, but I do recall a red design for the blood his brother had shed in defending the land of their white ancestor. He had the cape framed to protect it from soiling. What has become of it, I don’t know.

Malulani was closely associated with Timothy and Rosalie Montgomery before and after his retirement from being keeper of the Royal Mausoleum. This was also an office held by those of chiefly stock, for the guarding and care of the bones of royalty were never given to commoners. So far, those in the care of the Awesome were and are of chiefly stock, but of the future, who knows?

Malulani was succeeded by his cousin, William Kaiheʻekai Taylor. Then he lived with the Montgomerys until he chose to go to the Lunalilo Home, where he died.

He was skilled in feather work and in making the musical instruments used here in the islands, prior to the coming of foreigners to our shores.

I do not recall the year, but do remember the restoration of the kāhili in the tomb of Lunalilo. The kāhili there were in a deplorable condition, so the work of restoring them was assigned to Malulani Kāhea by William Taylor, who were both related to the king, entombed at Kawaiahaʻo. When the work was completed and the kāhili delivered at the City Hall, across the way from Kawaiahaʻo, Malulani walked outside of the building and called to the kāhili in a chant, to come forth. Those who were assigned the duty of carrying them — relatives, naturally — came out, formed a procession, and walked to the tomb where the restored kāhili were installed. I was there where I could observe without getting in the way, but it was Lahilahi Webb who was amid the crowd gathered there with the kāhili. It was she who told me that the kāhili chant was one that a relative of my mother’s, Kahōʻaleawai Kaluhiokalani, had brought to her at the Museum one day, saying, “One can not tell about life, so I brought this to you, in case it is needed when I am not here.” Uncle Kahōʻaleawai was not here when Lunalilo’s kāhili were restored; he was, as we Hawaiians say, “Moe kau a Hoʻoilo,” that is, sleeping the summer and winters away.

This Kahōʻaleawai was a chanter and was one of two people who chanted in the funeral procession of Queen Liliʻuokalani from the time her remains left ʻIolani Palace until she was laid away at Maunaʻala, the Royal Mausoleum. His companion was Mary Padeken, both beautiful chanters. They walked side by side, one chanting and the other listening. When the chanter’s voice gave out, the other repeated the last line and went on from there. I was much impressed by these two.

Many kāhili were borne in that procession, and among the kāhili bearers was my husband (Kaloliʻi Pukui).

When the Queen’s body was lying in state at the Kawaiahaʻo Church, I went at every opportunity to hear and to see. The tall kāhili stood in their places around her bier, but it was the waving of the hand kāhili that fascinated me most. A row of men or of women stood on either side of the bier, holding kāhili of uniform length and size. All moved in one direction, if to the right, then all to the right. Then a lift and a pause, then lowering gently together, all moved in unison to the left. Every move was timed exactly and perfectly. Each group remained for about an hour, then another group took their places behind the kāhili wavers and grasped the handles at the exact moment, while the others released their hold and stepped back as their replacements stepped forward. There was no break in the kāhili waving at any time, for each waver knew exactly what to do. Kāhili waving was not done in a haphazard way; there was an art to it.

It was Lahilahi who told me that the large kāhili were often dismantled and the feathers placed in containers to preserve them from dust and wear, but the hand kāhili were always in use. Only a few large kāhili were kept standing, but not all.

After the death of her beloved Queen, Liliʻuokalani, Lahilahi Webb became guide to exhibits in the Bishop Museum. When I first began working at the Museum, she was curious and unsure whether I knew anything, had any respect for them, etc., because I was young then. But as we became better acquainted, a lasting friendship grew between us, which ended with her death. I was Hawaiian-minded enough to understand and to respect whatever she talked about. Some young people were and still are inclined to scoff, rather than to listen well, to the tales of our ancestral culture.

When she realized that her sight was growing dim, she asked me to spend my noon periods with her, which I did. There I listened or discussed Hawaiiana with her and later wrote down lest I forget. There were many things that she knew in her youth, in her life in the royal courts, or things she had personally experienced.

Let me turn a page of my notebook and share this with you.

[The following section is by Mrs. Lahilahi Webb:]

“At one time, the Queen sent for us to come to her, asking that we younger women learn feather work from the older ones, saying, ‘If you do not learn, who is going to set up my kāhili when I am gone? Who is going to reconstruct and put them together, unless you learn now?’ We worked under Kaheana, a woman who was descended from a family of skilled feather workers known as poʻohulu. She knew the prayers, the ceremonies, and the kapu that had to be strictly observed. A poʻohulu was a kahuna of feather workers and had the same responsibilities that the kumu hula or hula master did in the hula school. A careless poʻohulu brought trouble to his workers, or to others. We felt honored to be chosen by the Queen for this work, which [was] accorded only to a special few. While working under Kaheana, none of us came during the menstrual period. If we came in contact with the dead, we had to go through a ceremony of purification. Physical, moral, and mental cleanliness were required of a person who handled the feathers of the chiefs. We not only made lei for the Queen, but also some of her kāhili.

Before a kāhili was moved from the place where it was made to the place where it was to stand, an offering of pig was made and appropriate prayers said. A small feast was always held before the moving of the kāhili. No kāhili was ever taken from place to place in broad daylight, only after nightfall when all was still.

Feather helmets (mahiole) and capes or cloaks (ʻahuʻula) were made by the men of the poʻohulu families. Nothing defiling was permitted when a helmet for the sacred head of the chief, or the covering for his shoulders, [was] made. In ancient days, women did not wear capes or cloaks until Kaʻahumanu broke the kapu by wearing one herself. There is a picture of Nāhiʻenaʻena wearing a cloak, made before the breaking of the kapu by Kaʻahumanu. Lucy Peabody explained that when a foreign artist made a picture of Kauikeaouli, Keōpūolani and Kaʻahumanu wanted one of Nāhiʻenaʻena too, but the child refused to pose until she was cloaked like her brother. In exasperation, the Queen gave in. Since that time, women wore and still wear replicas of feather cloaks or capes. When my Queen was in her last sickness, I was by her side constantly, for I was her nurse and companion for many years. As I dozed one night, I had a brief dream of seeing her favorite kāhili, that always stood by her bed, fall gradually until it rested beside her on the bed. I awoke and knew that the end had come for my beloved Queen. A few hours later, she breathed her last.

The Queen wanted her kāhili to come here to the Museum but we were told that there were already a large number there, so most of them were taken to the Queen Emma Museum instead. When the time came to move them there, I was asked to do it, having had experience with the old rules and regulations. The custom was to roast a pig, and offer it. I did my best. After the street cars had stopped running, Mrs. Julia Swanzy and I rode on the truck with the kāhili. On the way up Nuʻuanu, it rained but not a drop fell on us or the kāhili. Mrs. Swanzy did not know what to make of it, but I knew.

As you know, some years ago, Mokumaia of Maunalua was asked to make kāhili for the throne room where the legislature met. They were set by the portraits of our royalty and foreign nobility. When Mokumaia mentioned it to me, I gave him some of the feathers that belonged to Liliʻuokalani for the kāhili to stand beside her portrait. When that kāhili was finished, there were some left over feathers, so I gave more to another kāhili to stand by another portrait.

When the kāhili were finished and dedicated, I was not invited, and whatever they did I don’t know. Something must have gone amiss for many deaths occurred in the families of the members of both houses of the Legislature, and much talk arose about the kāhili. Perhaps the feather worker had broken a kapu, or they had not gone through a ceremony of purification before handling the feathers. There might have been ill feeling among them or things said that should not have been; who knows?”

Lahilahi sometimes walked with me into the feather room to look at those that stood in the cases there.

One of the most interesting to me was Kaʻulahoʻānolani, made by a part-Hawaiian as a gift to the Prince of Hawaiʻi when he was born. The original feathers were red and came from a foreign country. This was named by the makers themselves, for the redness of the feathers and the sacredness of the little chief. The handle of this particular kāhili was unlike any of the others, for it was of some kind of metal. It was Hawaiian and foreign too, like the ladies who made it with love for their Prince of Hawaiʻi.

The time came when the feathers became worn and fell to pieces, so in restoring the kāhili, albatross feathers were used. After it was restored, it was taken to the Museum.

The kāhili named Keaka was originally two, named Kūmoepili and Ehukuahiwi. Keaka, wife of Alapaʻinui, originally owned them, and it was she who gave them to Kamehameha I. They were handed down from Kamehameha I to Princess Ruth, and the feathers were those of chickens.

Lucy Peabody had heard from her grandmother, Kahaʻanapilo, that the feathers were baked in an imu before they were used in the kāhili, but was too young at the time to ask questions. The kāhili were kept and later dismantled at the Royal Mausoleum in accordance with King Kalākaua’s command. It was Liliʻuokalani who had them combined into one kāhili which was then given the name of its original owner, Keaka.

After the death of Prince Kawānanakoa, Lahilahi and a few others, especially selected, undid the two kāhili, under the guidance of Kaheana and Mrs. Mahiʻai Meek, for some of the feathers were falling to pieces. The good feathers were saved and made into one. The human bones in the kāhili were buried by the Queen in the grounds of Maunaʻala. She believes that they were the bones of the original owner Keaka, which were added after her death.

Keolohaka was a ruler’s kāhili and was owned by Kamehameha I, all the way down to Kamehameha V. When Princess Ruth inherited the properties of the Kamehamehas, she took this kāhili to the mausoleum at Maunaʻala and placed it at the head of Kauikeaouli’s coffin. The bones in the handle of this kāhili were those of the chief Keolohaka. The feathers were the ʻēʻē, or yellow wing feathers of the ʻōʻō. After the death of Queen Emma, King Kalākaua made an appointment to meet Lucy Peabody at the Mausoleum. She came accompanied by Grace Kahoaliʻi and heard from Liliʻuokalani that the King wished to have the kāhili dismantled. Liliʻuokalani ordered the human bones removed and buried in the grounds of Maunaʻala, and also that two kāhili be made of the feathers of this one. These were the kāhili that stood on either side of her during royal receptions. They stood beside her bed until after her death. Turtle shell and whale bone ivory were given by the Queen to be used for kāhili handles.

Also in the kāhili room was a beautiful hand kāhili made for Princess Pauahi Bishop. The handle was made largely of ivory and turtle shell and one may see the edges of dimes which had been pierced through the center and inserted with the ivory and turtle shell.

One big kāhili there appeared top heavy; the feathered part seemed too large for the length of the pole. I asked Lahilahi why it was so and was told by her that Dr. Brigham, the Director, ordered it cut so that it fit into the case. “And, the day came eventually,” she said, “when his own leg was amputated too.”

The kāhili that still retains its bones in the handle is Kaneoneo, and the bones are those of the high chief of that name. When Kūmahana was banished to Oʻahu, he moved to Kauaʻi, where his son Kaneoneo became the husband of the Queen Kamakahelei. Queen Kapiʻolani was a descendant of these chiefs. Kaneoneo came to Oʻahu, stirred a rebellion here, was taken captive and put to death. His bones were taken and the leg bone made into a kāhili handle. Abner Pākī had this handle and it was he who gave it to a Mr. Gilman. When Dr. Rooke was in New York, Mr. Gilman requested that he, Dr. Rooke, bring the handle to Queen Emma to kept by her mother, Fanny Kekela, in Lahaina, Maui. When the kāhili were ready to be placed in the Museum, Charles R. Bishop asked Lucy Peabody to add the feathers of the tropic bird.

Laʻikū and Malulani, Queen Emma’s kāhili, were made for her in Lanikeha, Lahaina, Maui and were of the ʻēʻē, the underwing feathers of the ʻōʻō and the long red tail feathers of the koaʻe or tropic bird. In the feathering they are identical but differ in the handle. Malulani is the ornamented one of the two, and it was for this kāhili that our beloved friend, Malulani Kāhea, was named. They, Laʻikū and Malulani, stood at the heads of the coffins of Kamehameha IV and the Prince of Hawaiʻi at Maunaʻala. The kāhili remained there until King Kalākaua ordered them dismantled, before removal. When Mr. Cartwright, trustee of Queen Emma’s estate, heard about the King’s wanting to take the kāhili, Cartwright placed Laʻikū and Malulani in the Bishop Museum. He asked Lucy Peabody about removing without dismantling them but the King objected to the removing without first dismantling. Then Lucy Peabody and Grace Kahoaliʻi came for them to place in the Museum.

The kāhili were royal standards of the chiefs, just as our country’s flag is to us. Respect is paid to them just as it is to the flag. We do not turn our backs at flag raising; nor do we let it fly in the darkness of the night. We salute it as it goes by. So it was with kāhili; we did not stand in front, with backs to it, but to one side when erected.

Royal kāhili were named, just as persons are, and chants composed in their honor. We have some of these in the Museum, which I translated years ago.

This is something else I received from Lahilahi Webb. After King Kalākaua returned from his world tour in 1881, preparations were made for his coronation. Feathers were sought for kāhili, capes etc. The only mention of these gathering of feathers are found in a set of chants called Mele Hulu, composed for Queen Kapiʻolani. The places mentioned in these chants as sources for the supply of feathers are Waimānalo, Mokumanu, and Mololani. Among the articles made was a bed spread of feathers and bolsters to match, for the King’s bed. The center of the spread was of ʻōʻō feathers, bordered by the reddish brown feathers of roosters (the moa ʻula hiwa). I have heard no one else speak of it, but I believe what Lahilahi told me, for she was devoted to her Queen, Liliʻuokalani, and remained with her to the end. Long after Lahilahi was gone, I saw a picture of that bedspread and the bolsters to match. Robert Van Dyke showed it to me. What happened to the bedspread after the coronation, nobody remembered.

Lahilahi was on the mainland when President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited the museum in 1934. A memorable day! I shall briefly mention the following incident. One kāhili was carried out to the court yard, “Eleʻeleualani.” Joseph Kamakau stood near it in full regalia, helmet and cloak, and beside him two young men wearing capes. Upon Lahilahi’s return, she asked me, “What kāhili was carried out and set up for the President?” I answered, “Eleʻeleualani.” “Good, very good,” she said. ʻEleʻeleualani, according to her, was owned by Keōpūolani, sacred wife of Kamehameha I. It was used in the funeral precession of her grandfather, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, when his remains were taken from Kaʻū to Haleokeawe in Kona. In the newspaper account, Kuokoa, Sept. 24, 1887, the owner was given as Lonoikamakahiki, showing it to be a very old kāhili. Hawaiʻiloa was another kāhili said to belong to him also. In the funeral procession, Hawaiʻiloa stood on the canoe occupied by Kīwalaʻō. ʻEleʻeleualani and Kauakaʻahonua were on the canoe preceding that of Keōuakūʻahuʻula.

Not only were kāhili named, but so were favorite spears, helmets, cloaks, capes etc. Named possessions were prized possessions, but unfortunately very few were ever recorded. We have heard of Nanikoki, the ivory pendant of Līloa, which led to a war between his son ʻUmi and Kulukulua, chief of Hilo. I was told that one of the helmets owned by Keaweamauhili was named Kalaniuiamamao, and the other ʻIouli. The two red coats given by Captain Vancouver to Kamehameha were named Kekupuohi and Keakualapu. All things worn by an aliʻi were kapu; any infringement called for severe punishment, even death.

Another feather worker I was closely associated with was Keahi Luahine, a direct descendant of Kaumualiʻi, last independent ruler of Kauaʻi by Pakakē, a chiefess of Hāʻena. It was from her that I learned the dances and chants of her island, with the promise that if anything happened to her, that I pass them on to her beloved grandniece and adopted daughter, ʻIolani Luahine, and to my children.

In April 1920, preparations were made to celebrate the centennial of the arrival of the first Congregational missionaries to Hawaii. Keahi made the kāhili for the pageant to be held at the Punahou School. When they were ready to leave home for the school, a feast was made and laid before the kāhili that night. Those participating in the ceremonial kāhili removal were Ahuʻena Taylor, Ethel Damon, and Jane Winne. After the feast, the kāhili were placed on the truck and taken to Punahou where they were to be used the next day. The hall where they were placed was first sprinkled with the water of purification before they could be brought in.

Keahi was to have gone to the school the next day to help dress the girls and women in their kīkepa, but she did not show up at all. When the kāhili were gone with the other ladies after the ceremonial feast, Keahi laid herself on the bed and had a brief dream. It seemed that the kāhili were back in the room where she kept them, in her house, and among them stood an elderly man who said to her, E Keahinuiokaluaokīlauea, name him Kahakuhulualiʻi (Maker-of-royal-feather-work). She awoke and the pain of labor came upon her. Between midnight and morning, a son was born to her.

Another dear lady who made beautiful feather articles was Annie Reist. I’ve seen beauty created with feathers that looked impossible, such as the flight feathers of birds. She, too, had a little room where she took her work for peace, quiet, and meditation. [She invited] to her home others of her age group, such as Lahilahi Webb, Mary Padeken, Haili Kamau and her husband Rev. William Kamau, who was then pastor of Kawaiahaʻo Church, Kīlauea Gumpfer, and others. Mary Padeken, like her sire before her, was a chanter, and many an evening, Birdie Reist and I sat off at one end of the latticed lānai to listen to a round of chanting with Mary, Rev. Kamau, and sometimes Lahilahi.

When the Queen’s birthday drew near, Lahilahi was unhappy at the thought of having no chanter to chant to Her Majesty. It was Wakeki Heleluhe who said to Lahilahi, “Why don’t you do it?” “But I am no chanter,” protested Lahilahi. “Never mind,” replied Wakeki, “let me teach you to kepakepa,” and so she did. On the Queen’s birthday, Lahilahi recited lovingly to her, “ʻO Liliʻu, ʻo Loloku, ʻo Walania i ke kiʻi ʻōnohi.” This chant I’ve heard in the Museum, chanted to the Queen’s portrait on the Queen’s birthday, day of her death, or whenever Lahilahi felt in the mood. She gave me a copy of it to add to my collection of chants.

I was not a member of the Sons and Daughters of the Hawaiian Warriors when Annie Reist, Mary Padeken, and Lahilahi Webb were living. Kīlauea Gumpfer was premier when I did and became better acquainted with another feather worker, Sarah Smythe, who was born on Molokaʻi. Listening, I learned, and all I learned, I respect. There is a time to talk and time not to.

Another feather worker I hold in respect was one of my instructors in the old dances of Kaʻū and Puna, Joseph ʻĪlālāʻole. I have never forgotten the day when one of his pupils held her ʻulīʻulī between her knees. “Don’t you see that that is feathered?” he said. “Feathers were for the aliʻi and for the images of gods, and what you are doing is disrespectful.” ʻĪlālāʻole made beautiful lei, a feather covered hat for his wife, and feathered bow ties for himself to wear and as gifts to particular friends.

James Lono McGuire’s and his mother’s kāhili and feather lei were works of art. I had seen them in his home when he was living. This was the man who started the rumor that peacock feathers were unlucky to possess, and began collecting the unwanted lei of the gullible, to finish the feather trimming of Queen Kapiʻolani’s holokū of blue velvet. He told me this story himself. After the death of the Queen, the holokū went to Kahanu, who was both a relative of hers, Kapiʻolani, and wife of her nephew, Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole. When the latter died, the holokū was sold at public auction where it was bought by Miss Vivienne Mader of New York, who was here at the time. She had hoped that the Bishop Museum or Daughters of Hawaiʻi would buy it for exactly what she paid for it, fifty dollars; no one showed any interest and so the holokū went to New York with her.

James McGuire accompanied Queen Kapiʻolani and Princess Liliʻuokalani to Queen Victoria’s jubilee in England. He kept a diary of this journey to England, all in Hawaiian, which he had published a few years before his death.

With the passing of time, much of our folk ways and customs were forgotten, and some folks began to believe that chiefs wore helmets and cloaks or capes at all times. They did not, but only on state occasions and in time of war. The men, noticing the colors or their leaders, rallied around them. Cloaks and capes were no more worn for every day than we would use formals today. There was a place for everything then, just as it is now.

Once while watching television, I was shocked to see a local football team on the mainland, in some kind of drill, led by one of the players wearing a cloak and helmet. It looked undignified. A cloak and helmet does not stand for all of Hawaiʻi, but for the royalty of Hawaiʻi. I wondered then how the people of England would feel to see an athlete striding about wearing a replica of the crown and ermine robes of their rulers; or the coat of arms of the nobility of Europe used as designs for rugs. Anyone declaring that the old Hawaiian feather work was not based on religion is sadly mistaken. Because this was not mentioned in any of the three books on feather work published by the Museum does not mean that it did not exist. It did, and in some places, with some persons, it does yet, except that the offerings of sacrifices have been eliminated.

Today, non-Hawaiians as well as Hawaiians make feather lei, for I have heard of one on Lānaʻi and another in Honolulu. Of the Hawaiians, there are some on all of the islands such as Edith Waiʻaleʻale (ʻIolani Luahine’s aunt) on Kauaʻi; Sarah Long Fernandez on Maui, Leilani Fernandez and Johannah Cluney on Oʻahu. I have heard of one at Waimea, Hawaiʻi, and I am sure there are several others. Of these people, I am best acquainted with the work of Johannah Cluney. I have seen some very dirty duck feathers delivered to her home one day, and when I saw them again they were clean and fluffy. Color combinations that seem impossible, blend to perfection with her. She had a badly soiled lei owned by the Museum and restored it to its former beauty.

I wish that before our royal insignia are carelessly used as rug designs, we Hawaiians be consulted first; then, it would have saved money on one side and indignation on the other.

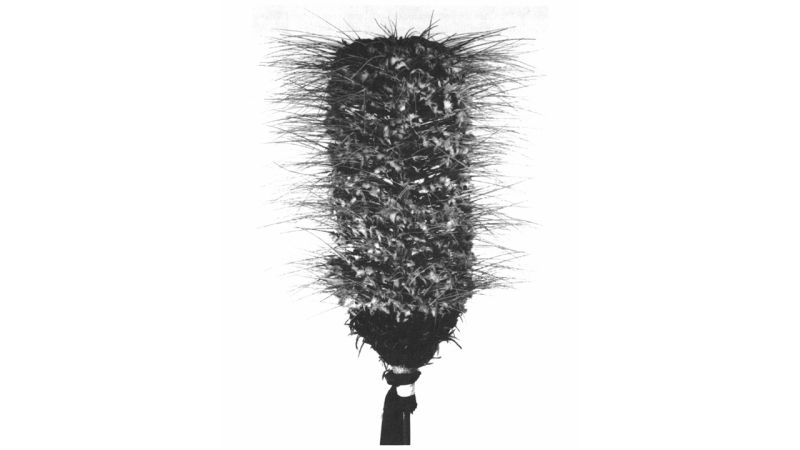

The twin kāhili, Laʻikū and Malulani.

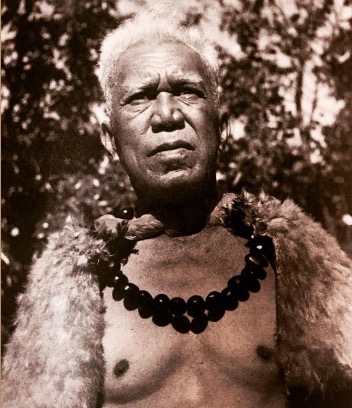

Fred Malulani Beckley Kāhea.

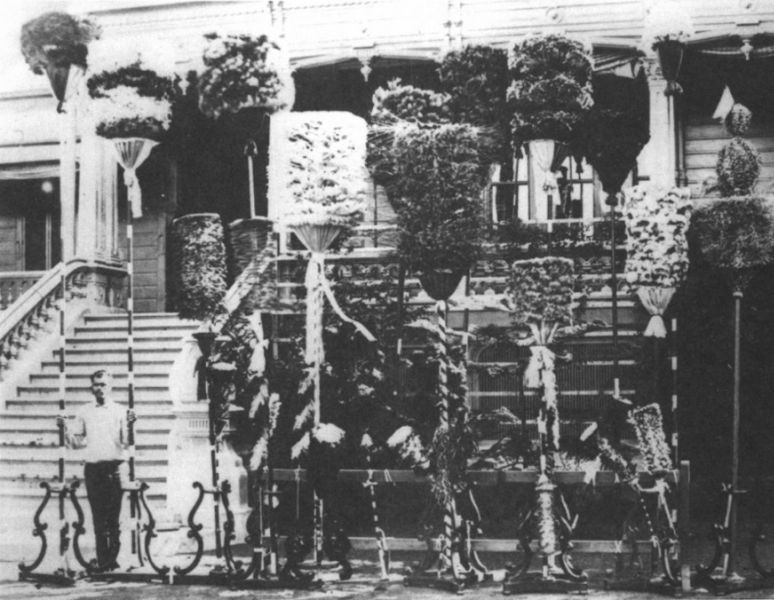

Some of the Kamehameha family kāhili assembled in front of Keōua hale, the house of Keʻelikōlani and Bernice P. Bishop, c. 1890. All of these kāhili are preserved in the Bishop Museum.

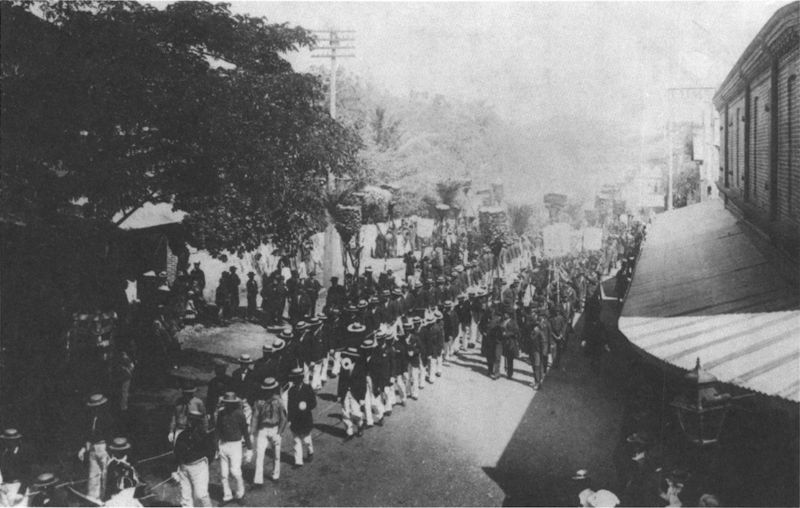

Kāhili in the funeral procession of Queen Emma from Kawaiahaʻo Church to the Royal Mausoleum, May 17, 1885.