Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Melehina Groves [Ka‘iwakīloumoku]

‘Ike ‘ia no ka loea i ke kuahu.

An expert is recognized by the altar he builds.

(Kawena Pukui, ‘Ōlelo No‘eau 1208)

This ‘ōlelo no‘eau explains that "it is what one does and how well he does it that shows whether he is an expert" in a particular area [1]. This idea is intrinsic to "Nānā i ke Kumu: Look to the Source," the latest in an exceptional monthly lecture series offered by the Bishop Museum. The Kūpuna Series has been celebrating the knowledge of our ancestors since April of 2000. This year, however, was the first year that the Kūpuna Series traveled to neighbor islands, visiting Lāna‘i, Kaua‘i, Kona, Moloka‘i, and Maui before returning for a final presentation on O‘ahu on August 27. The panel is composed of cultural practitioners who represent the very best in their diverse fields of expertise.

This year’s distinguished panel featured Kumu Hula Hōkūlani Holt-Padilla, ‘Ōlohe Lua Likeke Paglinawan, Kahuna Lā‘au Lapa‘au Levon ‘Ōhai, and Kumu Lawai‘a ‘Anakala Eddie Ka‘anānā. They are all masters in their own right, although each was quick to affirm that he or she had never envisioned one day being called a "master" or a "kumu."

"The purpose of the Kūpuna Series is to preserve, support, and perpetuate the knowledge of our kūpuna though workshops, lectures, seminars, hands-on demonstrations," and much more, said Chiya Hoapili, cultural education specialist for the Bishop Museum.

In spite of the diversity of their backgrounds, each practitioner agreed on one point which was stated very clearly by Kumu Hula Hōkūlani Holt-Padilla:

"No matter how much we know, we know very little," she emphasized. The true masters were their kūpuna, "fabulous and creative" individuals who made their discipline their life. She acknowledged that this may have surprised some people in the audience; you attend a lecture series with a panel of experts, perhaps looking for the "secret formula" to become a kumu hula, a kahuna, or a lua master . . . and you are told that the beginning of true knowledge is having humility in the face of all you have yet to learn. This realization can be a turning point for many haumāna.

‘Ōlohe Lua Likeke Paglinawan was first to share his mana‘o. He is an expert in the ancient Hawaiian art of lua, or hand-to-hand combat fighting that includes the use of offensive weapons such as spears, shark tooth daggers, and clubs. He shares the leadership of Ka Pā Ku‘i-a-Lua. His teacher was Charles Kenn, whose lua genealogy can be traced back to two of the five ali‘i who first studied at the royal lua school established by Kalākaua in the late 1800s. This genealogy, this strong kahua, is vital to Paglinawan.

"Lua is a way of life. It is not just to go out and fight," Paglinawan explained, pointing to the distinct set of values and lessons one learns as a student of lua. It is the kuleana, the responsibility of the teacher to pass those greater lessons on to his haumāna. "It takes years of dedication and commitment; it’s hard work over the long haul," he continued. (See Hawaiian language article related to this topic, "He ‘Ōlelo Hō‘eu‘eu.")

Holt-Padilla agreed with Paglinawan. She pointed out that although hula is "accessed by almost anyone in the world," it is not the accessibility—the simple ability to study hula—that gives a haumāna the fullest experience. Rather, it is the guidance and mentorship of a true master, those few who have made hula their life and are able to transmit knowledge to the haumāna as their kumu taught it to them.

"Creativity is a must, but you must maintain your traditions," Holt-Padilla continued, alluding to the importance of genealogy, of honoring your foundation, to the discipline of hula. "The kuahu is only good if the foundation is strong."

The qualities in a dancer also determine whether or not that haumana deserves to become a part of his or her kumu hula’s tradition.

"A good teacher can make a good dancer, but you can’t make desire, dedication, and passion. A kumu hula looks at all of those things," she explained. That is where the humility comes in, because even a talented dancer who lacks focus or simply expects to become a kumu hula herself oftentimes does not go far.

Kahuna Lā‘au Lapa‘au Levon ‘Ōhai echoed the words of the first two panelists and said a strong foundation in Ke Akua means he doesn’t have to worry about making the wrong choices. He learned the art of using Hawaiian medicinal plants for healing and preventing illness from his grandfather, who was born in the year 1900. ‘Ōhai was raised in a grass shack on the beach and learned at a young age that plants were vital to existence, because it was the grass of your hale that sheltered you from the elements.

To be a master in his discipline one must also learn to be humble, to accept that no one person has all the answers. He pointed to Polynesians’ widespread faith in Akua for their foundation in their varied arts and practices as a way of minimizing bad decisions in life.

Much like the other panelists, ‘Anakala Eddie Ka‘anānā echoed the notion of "ma ka hana ka ‘ike"—you learn by doing and your skill, your mastery, is reflected in your work. Talk is cheap.

"I figured I better make this thing to open up today, to show all of you folks that I could talk about this subject," ‘Anakala Eddie shared, showing us a small hook he had made that morning on his front porch in preparation for the discussion. This was important for the audience to see, because as he said, "not every Tom, Dick, and Harry can make these things; you have to be taught."

‘Anakala Eddie was raised by his kūpuna in the fishing village of Miloli‘i on Hawai‘i island. He is held in high esteem by many for his knowledge in the traditional style of fishing as it was practiced for generations in his family, as well as for his skill as a storyteller and farmer. If you are fortunate enough to sit and share some time with ‘Anakala Eddie, he undoubtedly will remind you to "ho‘olohe i ka leo"—listen to the leo, the words—of our kūpuna, as he has listened to them throughout his life.

‘Anakala Eddie can tell by the shape of a hook what type of fish was meant to be caught with it, but this is just one of the many things a lawai‘a must become skilled at before he can fish. He must learn the phases of the moon, the habits of different fish during those phases, how to fashion various tools, like the kēpau, the proper protocol for making bait, and much, much more.

Most importantly, there is mana in everything and proper ways to do everything. This is the most important lesson of a master.

‘Anakala Eddie shared that he was one of the last to learn the type of fishing that is traditionally practiced in Miloli‘i, which brings him to value this knowledge even more.

One very real concern shared by each panelist was a phenomenon Paglinawan referred to as the "putting up of shingles" by several people who pass themselves off as kumu hula, ‘ōlohe lua, or kahuna. In other words, they lead haumāna to believe that they are masters of a certain art, but they have not been trained in the proper way.

The real danger lies in the loss of authenticity and the weakening of the foundations of these cultural practices. Paglinawan expressed regret for the haumāna of these "shingle-people," the self-proclaimed kumu, because the haumāna are the ones being cheated out of the real thing.

Paglinawan cautioned prospective students to check into the genealogy of their kumu, because this is a way to help ensure the authenticity of a kumu hula, ‘ōlohe, or kahuna. "‘Ike ‘ia nō ka loea i ke kuahu – An expert is recognized by the altar he builds." In relation to our cultural practices, the importance of this idea is staggeringly clear. I feel we have cause for concern if these modern-day masters feel that too many of our kuahu are being built on foundations that are shaky at best. It is our kuleana to be maka‘ala, to be wary and watchful for these "shingle-people."

Paglinawan and Holt-Padilla both emphasized that in the old days when more true masters were still alive, they would surely have challenged these self-proclaimed kumu who do not come with a genealogy and who cannot answer the question, "A he mea ‘oe?"

Said Paglinawan, "If we are to perpetuate our culture, and these four arts are part of it, then let us make sure the quality of our perpetuation is there so future generations don’t get shortchanged."

[1] Pukui, Mary Kawena, ‘Ōlelo No‘eau: Hawaiian Proverbs & Poetical Sayings, 1983 p.131

photo credit: Chiya Hoapili

"Nānā i ke Kumu" panelists, from left to right: Kahuna Lāʻau Lapaʻau Levon ʻŌhai, Lawaiʻa ʻAnakala Eddie Kaʻanānā, Kumu Hula Hōkūlani Holt-Padilla, and ʻŌlohe Lua Likeke Paglinawan.

photo credit: Kaʻiwakīloumoku Staff

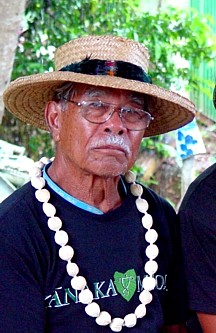

ʻAnakala Eddie Kaʻanānā, a master of many skills.

Kumu Hula Hōkūlani Holt-Padilla shared her manaʻo on the value of our kūpuna and their vast knowledge.