Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kawika Eyre

January 2004

Kāwika Eyre teaches Hawaiian language at Kamehameha Schools Kapālama campus high school. For the past two years he has been on reassignment conducting an oral history project relating to the KS controversy of the 1990s. Some 230 interviews are now stored in the KS Archives, covering all aspects of those times. Kāwika is a member of the Hawaiian Cultural Center Project Committee and a representative of Nā Kumu o Kamehameha. The following article is a speech Eyre gave at a retreat for members of Hui Ho‘ohawai‘i in January of 2004.

Aloha pumehana kākou e nā hoa makamaka o Kamehameha.

The word we are using for this conference, huliau, refers to a turning point, a time of change. Interestingly, another meaning of huliau is to think of the past, to recall what has happened. Coincidental to our topic this evening, Mrs. Pūku‘i gives the following example in the “Hawaiian Dictionary.” “Ua ‘ākoakoa mākou no ka huliau ‘ana.” We are gathered together to recall the past.

I have been asked by the HCCP committee to be our guide on this journey, this huliau ‘ana, that we may know something of whom we have been as we seek a path into our future. Several people have helped me as readers. Their suggestions and enthusiasm have been invaluable. Thank you Randie Fong, Janet Zisk, Ke‘ala Kwan, Nona Beamer and Dale Noble.

Much of the material I will present tonight was gathered during my recent two-year reassignment—as requested by Nā Kumu o Kamehameha and supported in part by a grant from the Parrent Fund. I was asked to interview people and write about the controversy of the mid-to-late 90s. Some of the material that follows is excerpted directly from a manuscript in progress. Much of it traces to archival sources. I am indebted to George Kanahele, Loring Hudson, the staff of KS publications over the years, and others. As they all have affirmed by their work, in our effort to understand ourselves, we must look to our past. Huliau.

In most ways our past begins with Pauahi. Surely the most quoted passage of Pauahi’s Will reads:

“I desire my trustees to provide first and chiefly a good education in the common English branches, and also instruction in morals and in such useful knowledge as may tend to make good and industrious men and women . . .”

Many have wondered and some have spoken much about what Pauahi may have meant by her words, “providing a good education in the common English branches.”

In Pauahi’s final years of life, 150 or 57% of the schools in Hawai‘i were conducted completely in Hawaiian, primarily using non-Hawaiian content from the curriculum of the common English school. Those of us working in Hawaiian have all studied the anatomy books, the math books, the geography books of this period, most—if not all—taken from the “common English branches” of the day and translated into Hawaiian. But by content, it was “common English branches.”

We might remind ourselves as well of Pauahi’s close relationship to her cousin Princess Ruth Ke‘elikōlani, a physically stern but warm-hearted woman, now widely admired for her staunch, steadfast support of Hawaiian language and culture. The few samples we have of Pauahi’s handwritten Hawaiian come from her letters to Ruth, who refused to use English.

To be sure, in many native families of that time, there was a growing recognition, resignation perhaps, that English was a necessary condition for success in a changing Hawaiian world. In September of 2002, the summer before her death, Gladys Brandt described the attitude of her parents some twenty years after the founding of the Schools: “My father and mother, like virtually all Hawaiians at that time, wanted their children to succeed, and they believed that to do so required their children to adopt Western ways. Unfortunately, they thought this was possible only by leaving behind the Hawaiian language and culture. If they were alive today, they would feel differently.”

And yet Pauahi, in her day, was praised as a woman who took the best of both worlds, a woman of the highest Hawaiian stature, a woman quite perfectly bi-lingual and bi-cultural.

What I am getting at here is that I find it very difficult to accept the notion that Pauahi would have looked on in any way approvingly at what was happening to Hawaiian language and culture at Kamehameha in those first years of her schools. That violence against the Hawaiian world strikes us today as unpardonable. Yet both Pauahi and the will remain silent on these matters: she left no guidelines for the fledgling school. She died before she could know.

Let’s go back in time to those first days at Kamehameha.

On November 4, 1887, King Kalākaua, then the embodiment of Hawaiian cultural revitalization—not the least hula—spoke to the students in Hawaiian at the dedication of Kamehameha School for Boys.

Standing near him and giving the formal prayer that day was Reverend Sereno E. Bishop, no relation to Charles Bishop, but the annexationist son of a missionary. Sereno Bishop was a haole who could speak Hawaiian. He prayed for the Kamehameha boys in their language. In English, whenever the subject of hula came up—and Bishop brought it up often in his Christian newspaper The Friend—he ranted.

So from the very start, standing side by side at that opening ceremony, were profoundly opposing views of something so quintessentially Hawaiian as the hula. Kalākaua would celebrate hula; Sereno Bishop would denigrate hula. Confusion, conflict of cultural identity from day one at Kamehameha School. And the issue of hula will run like a jolting live wire through the Kamehameha story.

Kalākaua and the Rev. Bishop stood that day at Kaiwi‘ula. Today, as we know, the Bishop Museum is located on this site. The name Kaiwi‘ula, which translates as “the red bone,” refers to a battle fought on these fields long, long ago.

In the early years of Kamehameha Schools, another battle was to be fought at this site, this one a quiet clash of cultures where teachers and staff of the young school purposely and relentlessly sought to stamp out the native language and all aspects of Hawaiian ways.

The first principal at Kamehameha was a man named William Oleson. The Reverend Oleson was a fervid democrat with no time for monarchies, and he had a particularly low opinion of Kalākaua as a king, saying that he ruled by bribery, corruption, lasciviousness, sorcery and tyranny. In the same year that Oleson took charge at Kamehameha, 1887, he was a member of a haole committee that forced a rewritten constitution on Kalākaua, sharply limiting the king’s power. This was the Bayonet Constitution.

One of the first orders William Oleson gave at Kamehameha was to ban the Hawaiian language. English was the only language accepted for the work time and play time of Pauahi’s school. Hawaiian was forbidden in the classroom and on the playing fields, and the boys were punished if they were heard speaking the language of their families. This was in the late 1880s and early 90s, which means that Hawaiian was banned at Kamehameha well before it was officially outlawed at Hawai‘i’s public and private schools in 1896, three years after the overthrow.

The anti-Hawaiian campaign at Kaiwi‘ula was relentless. Non-stop. For decades. Every teacher was to be a teacher of English. Every incentive was offered, every tactic tried: slogans, “Better English Weeks,” encouragement to sit in the library and read books, praise and prizes for pronunciation, speech contests, oratory at assemblies, discussion groups, debating societies, drama clubs, off-campus passes, free periods, an “English holiday” for anyone not caught talking “native” for a month.

Within three years, student compliance was showing in school statistics. The October 1890 issue of the KS publication Handicraft reported: “Thus far the average number of those who have earned the Holiday has been sixty-five percent of the number enrolled.”

In 1894, William Oleson co-wrote a book with a title that said much about this man who had led Kamehameha Schools. Its title: Picturesque Hawai‘i: A Charming Description of Her Unique History, Strange People, Exquisite Climate, Wondrous Volcanoes, Luxurious Productions, Beautiful Cities, Corrupt Monarchy, Recent Revolution and Provisional Government. His co-author was James L. Stevens, United States minister to Hawai‘i in 1893, who had ordered American troops ashore, effectively guaranteeing the overthrow of the monarchy. Stevens wanted nothing more or less than annexation, and Oleson was with him all the way.

Let us be clear: the boys under Oleson at Kamehameha were not American annexationists. They were Hawaiians, and they were instinctive royalists, reverential to their ali‘i nui. In the first years of the school, which were the last years of the monarchy, King Kalākaua paid a visit to a classroom. The boys stood of their own accord and sang “Hawai‘i Pono‘ī.” When Queen Lili‘uokalani visited and drank coffee, no one would touch her cup afterwards; it was sacred to the ali‘i, kapu.

As George Kanahele relates, following the 1893 overthrow of the kingdom, the boys voted with their feet against this school that was run by annexationists. So many boys left and did not come back that enrollment went down by almost half and stayed down for the next two years.

Newly appointed principal Theodore Richards replaced William Oleson. Richards’ approach to resolving the enrollment crisis was to depoliticize and Hawaiianize the school. He had a good feel for working with Kamehameha boys, and he had a great appreciation of Hawaiian music and language. He put Hawaiian songs on the glee club program alongside Western classical songs, to great success in performance.

That was really the only time in the first decades at Kamehameha when the Hawaiian language was given fuller voice. That, and in chapel at Kaumakapili Church, where the "Lord’s Prayer" was sung in Hawaiian. Other prayers and sermons also were in “native.”

Hawaiian music flourished at Kamehameha. Hawaiian dance did not. Reverend Sereno Bishop, who had given the prayer at the opening of the boys’ school, maintained his relationship with Kamehameha as well as his strong anti-hula convictions. The dance, he wrote, was “one of the foul florescenses” on the “great poison tree of idolatry.” Bishop said hula corroded Hawaiians—and labeled it moral leprosy. This attitude, though more mildly expressed, endured until 1965.

No right-minded principal at Kamehameha would want foul florescence and moral leprosy on his campus. No right-minded Bishop Estate trustee would want it on estate lands either. There were early leases that banned hula along with liquor. And among students it was rumored that language in Pauahi’s will expressly forbade hula. Not true. Hawaiian was not heard in the halls of Kamehameha and, increasingly, Hawaiian students at Kamehameha could no longer hear Hawaiian within themselves: the Handicraft issue of March, 1897 carried the following—to us—somber reflection:

“Five years ago the Rev. Sereno Bishop taught a class of Kamehameha boys in the Kaumakapili Sunday School. Then it was necessary for him to employ his excellent knowledge of the native tongue to make himself understood. After this interval, in which he has seen little of the boys, he comes back to preach to them and naturally he chooses the Hawaiian language in which to address them, and for the same reasons as before. It transpired that a census taken after the sermon disclosed the fact that several had difficulty in understanding him, and eleven boys from the Manual, twenty-one from the Preparatory and twenty-one from the Girls’ School did not understand Hawaiian at all.”

We should not be surprised by the success of Kamehameha at dismembering Hawaiian. Early Kamehameha was essentially an English immersion school. As our friends from the Pūnana Leo movement have so aptly demonstrated, immersion is the most powerful of language pedagogies. Since most of the students were boarders, the influence of the Hawaiian home was thoroughly lessened and the opportunity to immerse students in English optimal. Though the prohibition against Hawaiian was in place for many years to come, its existence grew increasingly irrelevant as the language vanished in the children.

But—and perhaps this reflects something of that same confusion we noted from day one at Kamehameha regarding attitudes towards hula—though Hawaiian language was officially banned at Kamehameha, it was never completely rejected. Indeed a cynic—or a careful historian—might detect an increase in the lip-service paid “things Hawaiian” at a rate roughly equivalent to the actual decrease in authentic “Hawaiian things” at Kamehameha. The word tokenism creeps into our vocabulary when speaking of these years.

By 1900, for example, students were permitted, even encouraged to participate in non-and extra-curricular opportunities to learn and practice their native heritage. Kamehameha School for Girls’ students took short, off-campus excursions to the surrounding mountains where they sang Hawaiian songs and danced hula, though in sitting position we may presume. The school newspaper of the time, The Blue and White, often had articles, in Hawaiian occasionally, highlighting or explaining Hawaiian music and legends. Students from the boys’ and girls’ schools built and entered a float depicting kapa making in the fifth annual Floral Parade of Honolulu. They won the grand prize for Best Decorated Float.

In KS music classes, Hawaiian songs were taught alongside American and European compositions. Well-known composer and alumnus Charles E. King taught music at the schools from 1900 through 1902. In his teaching, he placed special emphasis on Hawaiian songs and melodies. Hawaiian mele were practiced and performed for the annual Founder’s Day.

Guest speakers (usually not Hawaiian) addressed the students, encouraging them to practice their culture and language.

For example, on March 22, 1902, The Blue and White reported: “On Friday evening Mr. Frank Archer of Pearl City delivered a fine address to the girls in Hawaiian. His subject was ‘Children, Obey Your Parents!’ His points were beautifully expressed and held the attention of every pupil.”

A year later The Blue and White reported that “On Feb. 28, 1903, a missionary meeting, conducted by Rev. O. Gulick was held in our Assembly Hall. He told us of the missionary work that is being done among the Japanese on these Islands and also about some of the customs and characteristics of the Japanese. He spoke first in English and, at the close, in Hawaiian. He reminded us of the beauty of the Hawaiian language and that we must not forget our mother tongue.”

Reverend Gulick, in 1908, again spoke to the first grade students at the girls’ school. He closed once again by reminding the children of the beauty of the Hawaiian language, and that they must not forget their mother tongue.

The comment to me almost gratuitously belies the horrific reality of the context of the day. In 1908, all around Hawai‘i, including Kamehameha, first graders were being whacked, yelled at and kept after school for speaking their native tongue in the classroom and on the playground.

The mixture of messages is mind-boggling to us: don’t forget your mother tongue and for sure don’t you dare speak it while at Kamehameha! And we know from kūpuna that the slow pounding in of the unworthiness of Hawaiianess was soul-wrenching for Hawaiian youth.

One kupuna and keiki of those days, Gladys Brandt, in interview late in life, remembered bitterly the sense of shame she felt at being Hawaiian. She was born in 1906 to David Kanuha, who was the tailor at the Boys’ School, and Esther Staines, who was in the first KSG graduating class. As a young girl observing the students, Gladys noticed that they were using lemon juice to rub out the stains from their white dresses, the uniform of their day. The impressionable Gladys sneaked a couple of lemons and, in her hiding place, rubbed the juice hard into her skin. To lighten it. To whiten it. Her shame was not just skin deep. It dug bone deep. It dug down Hawaiian soul deep.

In the early 1920s, the advent of Song Contest provided two or more Hawaiian songs per student per year. We don’t have statistics on this, but we think that very few students by now had even at best more than a meager understanding of their native language. Thus begins a long tradition at Kamehameha of native children singing beautiful Hawaiian songs of which they have little or no understanding. A tradition that extends through most of the schooling years of those seated here tonight, and, to a certain extent, continues today.

Publicly, attitudes toward Hawaiian were often tolerant: one-time principal and teacher at Kamehameha School for Boys, Uldrick Thompson, in a 1920 campus presentation, reminded the students of the beauty and intelligence of the Hawaiian language, culture, and people.

Privately, back in the dorms, attitudes were hardly so upbeat: Zena Schuman in interview some ten years ago, described how Hawaiian language was allowed only in the laundry room on laundry days at KSG. She also described how, on Saturday evenings, having posted lookouts down the hallways and near the front steps, the young women would line up on the beautiful double-curved stairway of the old KSG residence at Kaiwi‘ula. The coast clear, they would whisper their songs and dance gently as they stood on the dark wood stairs.

But there was to be change. In 1924 Lydia K. Aholo, hānai daughter of Lili‘uokalani, graduate of Kamehameha School for Girls and Oberlin College, became the first formal instructor of Hawaiian language at Kamehameha Schools. A torch is lit in a culturally darkened school!

This 1924–25 school year course in Hawaiian was compulsory for all seniors. Students received three hours of Hawaiian language instruction a week, using as textbooks the Hawaiian translation of the Bible and the Life of Lincoln. The student paper, Ka Mō‘ī, recognized this course as one of the highlights of the year.

However, this first attempt at formal teaching of Hawaiian language lasted only that one year.

In a letter dated April 14, 1978, Frank Midkiff, KS president and later trustee, reminisced: “In the early 1920s, I thought it would be good to help our young people learn Hawaiian. So we got the trustees to make Hawaiian language a required course. The students were very interested in it and happy. But soon several parents came in and objected. ‘Why do you teach our children Hawaiian? We can do that ourselves. Before, here, our children were punished if they spoke Hawaiian. They were required to speak English. That is what they need. Punahou, St. Louis, the public schools don’t teach Hawaiian. You should teach them Latin or French or German. The University of Hawai‘i and other colleges won’t give them credit for studying Hawaiian . . . to enter or for graduation.’

Midkiff continues: “I hated to give up what I knew was good for them. I took it to the trustees. The parents had talked to the trustees before me. The trustees said, ‘Well, let’s make it elective. Maybe that will be acceptable.’ But before long, after it was made elective, several gave it up and before long the courses had to be withdrawn. All followed the parents’ inclination and the teaching of Hawaiian language and culture was given up for that time being.”

But Midkiff, a speaker of Hawaiian, did not give up. Later that year, he and Dr. John H. Wise, a professor of Hawaiian language at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, wrote and published a Hawaiian language textbook, A First Course in Hawaiian Language.

Nor, it seems, did the students give up on wanting more Hawaiian. This quote is from the KS Archives Memory Book Vol. V 1924–27, but without specific date: “A regular meeting of the combined student councils of the Kamehameha schools was held to discuss the question ‘What should be added or dropped from the present course of study? Lawrence Chang spoke on behalf of the tenth grade boys. He suggested a special course in the Hawaiian language. Abigail Ka‘aloa expressed that the tenth grade girls also desired a special course in Hawaiian . . .”

One year later, and two years after the first Hawaiian language course was dropped, John Wise was hired and Hawaiian was reinstated in the curriculum, using the Midkiff/Wise textbook. Another cultural torch is lit at Kamehameha.

While Hawaiian language from this date on seems to be finding a modest place in the KS curriculum, hula definitely is not.

In 1929, according to Kanahele, a group of alumni held a fundraiser on campus. For scholarships. The hula was danced. Twice. It was for a good cause. But the principals of the girls’ school and the preparatory school, Maude Schaeffer and Maude Post, were outraged and agitated. They went to the trustees, saying that “dances of this nature tended to neutralize the strenuous efforts made by the teaching force to obliterate certain undesirable racial tendencies in the students.” The trustees agreed that a strict watch should be maintained to see that nothing further of this kind was permitted on campus or at affairs with which the schools were in any way connected.

The young ‘Iolani Luahine, enrolled at Kamehameha during these years, was withdrawn when her aunty and kumu hula Keahi Luahine became aware of the missionary attitudes against hula on campus. We have no date on this but ‘Iolani did graduate from St. Andrew’s Priory with the class of 1935.

Several years ago Papa Henry ‘Auwae met with our students and bitterly reminisced over the fact that he, too, had to leave Kamehameha about this time. Thrown out for repeatedly speaking Hawaiian.

In 1930, Dr. Donald Mitchell from Great Bend, Kansas, joined the staff as an instructor of English.

Dr. Mitchell started a club for Kamehameha boys in 1931 that allowed them to study and practice Hawaiian cultural traditions. Hui ‘Ōiwi, regularly met to learn and demonstrate Hawaiian cultural practices, especially games. From 1930 until the 1960s, the yearbooks of the Schools often published pictures of the club’s activities, most often showing handsome, brown boys in malo, demonstrating traditional Hawaiian games. Membership in the club was by invitation only. Years later, 1941 graduate Roy Benham noted the popularity of the club:

“Oh yeah, everybody wanted to join . . . it was a good club. I teased Don about that when I went back to teach. He was still there. I said, Don, the only reason you didn’t select me for Hui ‘Ōiwi was that my ‘okole was too white. You know it just seemed to me that you were selecting the real Hawaiian looking ones.”

In the spring of 1931, as part of a new plan for education, Dr. Homer F. Barnes, recently appointed principal of the School for Boys, dropped the Hawaiian language class from the curriculum. In an undated newspaper article from that period, Dr. Barnes offers forth the reason for the change as being a great opportunity for higher scholarship and adjustment of teaching loads.

Immediately after this announcement, the staff at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum arranged for Kamehameha Schools’ students to take Hawaiian culture classes at the museum in place of the dropped language classes. Lectures were initially conducted for seniors on a weekly basis, later to be published by the KS Press in 1933 in a 300-page book entitled Ancient Hawaiian Civilization.

Sometime in 1935, several seventh grade girls approached classmate Winona Beamer—already a young cultural torch to her friends—and asked her to help them learn the renowned chants and songs of the Beamer family. Hui Kumulipo, the girls’ club for Hawaiian culture, was born.

Hui Kumulipo came together with Hui ‘Ōiwi a few times a year for joint Hawaiian cultural activities, the most anticipated of these being the annual May lū‘au, prepared by the boys and girls in the traditional manner.

During the coming years when Hawaiian language classes started, stopped, and started again, the Hawaiian clubs of Kamehameha Schools were the only venue for the recognition, encouragement and practice of Hawaiian knowledge.

At one such club-sponsored occasion, Mary Kawena Pūku‘i brought her hānai daughter Pat Bacon up to campus for a KSG assembly and the beautiful girl did a standing hula. Winona Beamer, chafing as she must that Kamehameha girls could not stand and dance but only watch, was furious at what she saw rightly as administrative duplicity. Much to the astonishment of her classmates, Winona stood up and stomped out of the assembly.

Nona was not your everyday, docile student. In 1937, as a 9th grader she was kicked out of Kamehameha, charged with doing a standing hula. The occasion was the “Trustees’ Tea” held on a Friday afternoon in the area known as “The Pink Garden.” The chant was the “Oli Aloha.” It was this chant that welcomed you here this evening. Winona had known it from her earliest years.

As she walked in, chanting for the trustees that afternoon, Winona’s hand gestures and body movements slipped ever so slightly away from her. Musical as she was, she became one with her chant. When she finished, principal Maude Schaeffer stood up, strode over to her, and announced: “Winona! You may pack your bags!” Winona, had crossed the line and violated the ban on standing hula at Kamehameha.

In a interview in 2003, Aunty Nona described how incensed she was: “I carried my bag all the way down to the gate and I was fuming! Just fuming!” Over that weekend Maude Schaeffer apparently had second thoughts. Winona was reinstated the following week.

During the war years, Ka Mō‘ī ran columns on Hawaiian language entitled “Nā Ha‘awina Hawai‘i.” These included glossary and 10 or more sample sentences listed in both Hawaiian and English. A September 1943 lesson is prefaced: “The Hui ‘Ōiwi is sponsoring this column for the third year with the hope that the Kamehameha students will learn more of the language of their ancestors through these simple, practical lessons. A sincere ‘Mahalo nui’ to Mrs. Mary Kawena Pūku‘i of the Bishop Museum for her invaluable aid.”

Conversational Hawaiian was introduced in the elementary and intermediate divisions in 1944. Mrs. Pūku‘i was the teacher. Many of the stories she used were later published in her books with Caroline Curtis.

Reverend Stephen Desha, the Kamehameha Schools’ chaplain, led a once a week non-credit Hawaiian class for junior and senior boys and girls. The student newspaper reported that “[N]ow Kamehameha boys and girls are encouraged to speak and write in their native tongue . . . The class has been working on the use of every day words and terms. Such things as names of districts and locations are being studied. As time passes, the class is striving to bring the culture of Hawai‘i nearer to the youth of the islands.” Again, this was a once a week, non-credit class.

That same year, 1944, the student paper carried a rather curious message on the subject of hula at Kamehameha. It was from Mary Frances Barnes, the wife of Homer Barnes, Boys’ School principal since 1931. She had learned the ‘ukulele and traditional Hawaiian nose flute, and had studied hula from Winona Beamer’s mother. Aunty Nona would later exclaim: “It just galled me to the quick that she could come and study with my mother and I couldn’t do any of these dances that my mother had taught me!”

When her husband resigned in 1944, Mary Barnes left this parting message in Ka Mō‘ī: “I wish I could create in all of you so much respect for this beautiful dance, that you would use all your influence to keep it worthy of the respect it deserves. I wish hulas were danced on every occasion as an inspiration to all who see them.”

It was not to happen legally for another twenty and more years.

In 1946, President Harold Kent assumed the presidency of Kamehameha and in his first public statement offered the following: “It will be my sole purpose to sincerely develop the schools so that they may be of the greatest service to the Hawaiian people through developing in character and leadership an ever-growing number of their youth, and through perpetuating in every wholesome and thorough way the finest aspects of the glorious Hawaiian culture.”

The standing hula did not qualify with Colonel Kent as fine and glorious and wholesome. Kent was the incarnation of the most respectable Protestant Christianity, and the standing hula embodied other Hawaiian things.

In the spring of 1947, Harold Kent established a Hawaiian Culture Committee to study various phases of the culture that might be incorporated into the curriculum. Don Mitchell was appointed head of the committee, which included many cultural luminaries of the day, among them Rev. Stephen Desha, Mrs. Mary Pūku‘i, Miss Margaret Titcomb, Miss Beatrice Mo‘okini, Dr. Kenneth P. Emory, Miss Caroline Curtis, and Mrs. Dorothy Kahananui Gillette.

The decade of the 50s was one of numerous publications—the culture of the written word. The collaboration of Pūku‘i/Curtis produced such titles as “Pīkoi,” “Water of Kāne,” and “Tales of the Menehune.”

From 1951–53 Ka Mō‘ī ran a column in Hawaiian, student-authored by Jean Kelly of Ni‘ihau, James Merseberg, William Kaina and David Ka‘upu, at times writing together, at times individually. With the graduation of the “three kahu” in 1951, Jean Kelly continued the series.

Significantly, from 1952 until 1964, Dr. Mitchell designed and taught courses for KS students at the Bishop Museum. The students worked closely with artifacts and became museum guides to thousands of public and private school children who visited the museum each year. This is seen as the most successful collaboration to date between Kamehameha and the museum.

The lessons developed by Dr. Mitchell for the students were first published by KS in 1969 as “Resource Units in Hawaiian Culture.” It remains an important work to this day.

Other powerful—if more covert—Hawaiian lessons were reaching students as well: living, formative lessons that would contribute to the breaking of the kapu on standing hula some ten years later. In the mid-1950s Aunty Nona Beamer began teaching hula classes in the Dorm M laundry room. Standing hula. In violation of KS rules. We’ll come back to this.

The absolute crowning achievement in Hawaiian cultural publications in the decade of the fifties was the appearance in 1957 of the Pūku‘i/Elbert “Hawaiian Dictionary,” the springboard for so much that has happened in Hawaiian language and culture ever since.

In 1961, Hawaiian was added to the list of “foreign” languages available to the students in the two upper schools. Ka Mō‘ī of March 10, 1961, mentions 24 students were enrolled the first year and 27 in 1962.

Later that month President Kent noted that “Hawaiian language is now taught in the seventh and eighth grades at the Kamehameha Preparatory Department.” And he added what he called “other tangential uses of Hawaiian at the Schools”:

During this period, Mrs. Dorothy M. Kahananui was asked to prepare teaching materials in Hawaiian. By 1965, a 175-page textbook entitled E Pāpā‘ōlelo Kākou was completed. Mrs. Kahananui began teaching Hawaiian language to ninth grade students, the first elective course in what was to be a three-year sequence.

In the years that followed, formal Hawaiian language teaching gained a foothold on the Kapālama campus of the Kamehameha Schools. But this was by no means a widespread, exuberant affirmation of Kamehameha’s Hawaiianess. Sarah Quick Keahi, who taught Hawaiian for 37 years from 1966 to 2003, recalls Kamehameha then:

“When I first came to Kamehameha, Hawaiian was really the orphan of the institution . . . You should take French or Spanish . . . the top students didn’t take Hawaiian . . . And I guess coming from the public school I had this idea that everybody at Kamehameha knew about Hawaiian. And I came here and I thought ‘Wow, that’s not true at all! They don’t know anything!’ There wasn’t anything in Hawaiian studies. Dr. Mitchell’s course was seen as “enrichment,” not academic. And I thought, ‘Wow!’ And so we made this proposal year after year after year. Finally they did a graduate survey and the graduates said that when they went to the mainland, people asked them about Hawai‘i and Hawaiians and they couldn’t answer intelligently. Finally, after community pressure and the graduate survey, it became a reality. Prior to that we had proposed it for our students for seven years in a row.”

By far the most dramatic event of this decade, however, occurred the year before Sarah started teaching when, in 1965, the kapu on standing hula was broken. This is a story of many cultural torches.

Breaking the kapu took a concerted campaign, the determined acts of students, appeals from teachers, comparisons with dance culture worldwide, authoritative testimony from Donald Kilolani Mitchell, and a lobbying campaign at Bishop Estate headquarters spear-headed by Gladys Brandt, principal of KSG.

To trace the beginnings of defiance on this one, as mentioned earlier, we must return to the mid-1950s and Aunty Nona Beamer’s lessons in the laundry room of Dorm M. In interview she recollects:

“. . . I was half-time for 10 years. There was no Hawaiian Studies department. But the students were asking. And my classroom was in the laundry, in the dorm. With the machines going. You could smell the soap and Clorox. And big pillars in the middle of the classroom, so you kinda had to peer around them to see the students. And then the boys asked if they could come, ‘cause we were the Girls’ School. And I said sure, come on up! So they’d trudge up the hill and only had like ten minutes passing time, so they’d be late getting there, and then have to leave early to go back down.”

A couple of years later, an unsung hero of this story, PE teacher Midge Mossman, began to include hula in her classes. Nona Beamer describes Midge thus in a 2003 interview: “Her enthusiasm was unbounded. And her love . . . I think her love is just unsurmounted. It really was . . . No boundaries to her enthusiasm. Her love just surrounded everything she did. She was a remarkable gal.”

And—as a wonderful reminder to us of the power of teaching—both of these young women were speaking strongly to their students about the pride they should feel in being Hawaiian.

When asked in interview if she remembered such conversations with Mrs. Beamer, Vicky Holt-Takamine, class of ’65, exclaimed: “Oh! Very much so! Very much so! I mean she would tell us, ‘You need to be proud of who you are as Hawaiians . . . We have a very rich culture . . . We have many traditions. We are a people of, of, of,’ What did she say? ‘A people of spirit. Of love.’”

Vicky was being influenced as well by another strong source from outside the walls of Kamehameha, a hula studio on Ke‘eaumoku Street where standing hula was taken very seriously. Again Vicky: “Well, when I got to high school . . . I was a student of Maiki Aiu Lake. And . . . I had question marks on a lot of things.” Vicky wasn’t the only student who questioned KS policy on hula. Other students who danced “outside” included Kanani Kalama and Louise Beamer, a niece of Aunty Nona.

In an article in Ka Mō‘ī dated March 26, 1965, senior Louise Beamer spoke of her love for hula almost flauntingly as she quipped, “You name them, I do them!” Because of her skills, Louise was an assistant dance instructor at the Kamehameha Karnival Hawaiian Show that year, scheduled for Friday, April 2.

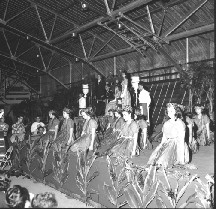

The Hawaiian show at the old Kekūhaupi‘o hangar was to start at 7:30pm. It was entitled “He Inoa No Kalākaua”. You will recall that it was Kalākaua who spoke at the school’s dedication, standing next to the anti-hula Sereno Bishop. The article in Ka Mō‘ī ends with a cautionary reminder that “all hula will be performed in sitting position.”

It was not to be. Some days earlier, Louise Beamer had performed the song “Kawohikūkapulani,” written by her great grandmother, Aunty Nona’s grandmother. Louise performed it standing in front of students, for which she was firmly chastised. The students were shocked. Angry.

Meanwhile, and backtracking just a bit, behind the scenes that spring, less public calls for change were coming from teachers and administrators in the form of letters to the trustees. In early February, President Bushong wrote, suggesting that the time had come to allow standing hula.

The trustees responded: “Please confer with Miss Nona Beamer, dancing instructor at the schools, determining from her the cultural aspects of the hula which are presently being taught.” The information came back not from Nona but from Don Mitchell. In a letter dated February 16, he summarized the view on this matter from the Bishop Museum: “Knowledgeable staff there,” he noted, “recognized that this form of expression was and still remains a dance of grace, beauty and meaning. The story of Hawai‘i could not be understood without it. Mary Kawena Pūku‘i has said for many years that Kamehameha should teach and perpetuate the very best in traditional hula, including the standing forms. And teach the very best versions.”

The following day, February 16th, 1965, PE teacher Midge Mossman in a three-page, single-spaced, typed memo of her own passionately argued the virtues of standing hula:

“The ancient form of the dance accompanies the chant as the modern interpretative dances accompany the modern Hawaiian melodies. Both are a definite part of our culture. The ancient is not the only hula . . . Both dance forms evolved out of the same culture but at different times and both have equal merit . . .”

That was an argument from culture. There was another argument. Again, Midge Mossman: “There seems to be a double standard that will be evident this year in our Kamehameha Karnival. The dancers in the Hawaiian Show will not be permitted to do standing hulas, yet the dancers in the Shindig Show will be dancing the Monkey and the rock-and-roll dances in their choreography.”

James Bushong, whose wife was a student of Nona Beamer’s mother, took the broad view. “In Italy, Russia and other countries their national ballet has achieved world acclaim for variety, intricacy and expression of movement. In similar fashion, the traditional hula epitomizes the historic culture of Hawai‘i.”

While the adult conversations would continue, the students’ impatience would not wait. The Karnival Show was on Friday, April 2. In a recent interview, Kaho‘onei Panoke, who was very involved in the show, recalls the growing student unrest as that date approached:

“. . . It was really driven by the students because after what happened to Louise . . . we decided, ‘No, this cannot go on . . . We are Hawaiians. Standing hula is part of our culture.’ And then they said, ʻWell, you can do standing hula but you can only do the motions. You can’t do any body movement to it.’ And we said, ʻNo, that would be unacceptable.’”

As if to heighten the dramatic tension of this historic moment, the students that evening initially complied. Until the last dance that is, which was “Kaulana Nā Pua.” For that they stood.

Vicky Holt-Takamine, who was Karnival Queen, recalls: “We did it consciously. It was a perfect number for that . . . we didn’t want to sit down and do hula. And I think that Kanani Kalama was one that took the lead on that . . . saying, “You know, we have to stand up and do this. We just can’t sit down . . .”

This was a turning point. Huliau. Those students standing tall on stage that evening are for me the many standing torches . . . Kū ka lau lama!

Emerging out of that 1965 Kamehameha Karnival was the sense in the minds of the students that the stage that evening was the birthplace of the first Hō‘ike. Those dancers would go on in the coming months to form what to this day is called the Hawaiian Ensemble.

The group, which included sophomores, juniors and soon-to-graduate seniors, then began preparing for a trip to Japan. Kalani Cockett, who worked with the Hawai‘i Visitors’ Bureau and had helped out with the Karnival, wanted to take the students on a cultural exchange.

The students practiced several times a week all that spring. Publicly. Right spang in front of Ka‘ahumanu Gym. If there lingered any question in the high school students as to whether standing hula was still not happening on campus, their questions were quickly dissipated by those very public rehearsals. Again, Vicky Holt-Takamine, this time with a kolohe twinkle to her voice:

“We did standing hula! We did Tahitian! We did Maori! We shook our bodies all over campus that summer!”

It was this group, now officially called the Hawaiian Ensemble, which presented the first Hō‘ike during the judges tally at the Song Contest in the spring of 1966. The show included standing hula and was greeted enthusiastically. The classes of ’65, ’66 and ’67 have never quite received the recognition they deserve for helping to change the culture of Kamehameha so profoundly. As for the singing that night, it was a senior sweep!

Meanwhile, rewinding back to the adults and the spring of 1965: President Bushong did not want to have to lobby the trustees. He told Gladys Brandt to do it.

The first one she spoke with was trustee Richard Lyman. He told her to forget about it, which only made her all the more determined to go after the others.

Second was Atherton Richards, son of Theodore Richards, the musical principal of Kamehameha who was in charge of the school when Gladys’s father taught there. Atherton Richards liked Gladys. He used to send his car to campus to bring her to parties at his house on the beach at Diamond Head. There was dancing on the beautiful lawns, standing hula, and some of the dancers were Kamehameha girls. Gladys pointed this out to Richards. Yes, he said, but they were graduates. But then he said yes to Gladys.

Next was Frank Midkiff, the enlightened Schools’ president from the 1920s, old now. It was hard going with him, but eventually he said yes. So did Herbert Keppeler.

Then Gladys got a call from Richard Lyman. He had reconsidered. That was a fourth yes. “One to go,” he said, and he laughed. “You will not pass this one!”

“This one” was Edwin Murray. KS graduate and Hawaiian trustee—the trustee whom fellow trustees referred to as having forgotten he was Hawaiian. Gladys had a hula history of her own with Murray. Not long before, she had been in charge of the entertainment at an event for the trustees on campus. From the way she described the setting in interview, the event was probably held at the Administrative Building on the Lānai Terrace: tables on the lawn, Hawaiian food, and ‘Iolani Luahine, dancing, beautifully. You will recall that ‘Iolani had left KS in the ’30s because of the hula policy.

In the middle of the performance, Gladys looked around for Murray. He was gone. She spotted him, went over to him and said, “Isn’t she lovely?” Murray took his cigar out of his mouth—he always had a cigar—and said, “She dances like she has ants in her pants.”

In the coming days, Gladys made an appointment to see Murray at Bishop Estate headquarters. It was a fiasco. Murray grumbled he had no idea that she had come to Kamehameha to promote indecency. Gladys did not take this well.

Again, in interview: “I just went haywire. I just thought I got slapped in my face left and right. I lost my cool. I was just rocking all over the place. I thought I would use every four-letter word at him. His chair flew back. I said something about the military, missionary ethic and all that kind of dumb thing. I should have known better—that he was my father’s vintage. They were like each other. I was terrible. I went out bawling.”

She got back to campus, and there was a message to call Murray. “I thought I was being fired. So I thought, well, I hope Kaua‘i will give me a job.” She phoned him. “He called me ‘woman.’ I will never forget that. ‘Woman!’ he said, ‘I got a table for my family, and if those girls wiggle too much, you know where you’ll be!’ And bang went the phone.”

Gladys dried her eyes, blew her nose. Murray had booked a table for the annual Holokū Ball at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel and now the girls would dance.

The evening was a huge success, applause and more applause after each of the dances. Murray was there. He sat through it. Next day the papers ran a big story. Seventy-eight years after the dedication ceremony at Kaiwi‘ula, standing hula had official standing at Kamehameha.

Well, almost. The story wasn’t quite over yet. “The performance of mele ma‘i,” says Randie Fong in a recent email, “was banned through the ’80s. An administrator was actually assigned to review the Hō‘ike for ʻappropriateness’ until we decided to do ʻ‘Anapau’ in 1988 and asserted control over the repertoire. Subsequently, administrative reviews ceased and we’ve since then felt free to include sexual references whenever and wherever appropriate.”

Echoes of the early ’60s when Nona Beamer’s lesson plans were regularly scrutinized by administrators for “lascivious” content.

At this point, for the sake of time, I would like to move ahead rather quickly.

We have included a historic overview in your binder, written in 1975 by Don Mitchell and Nani Bowman which does a good job of recapping some of what I have covered this evening and also tells much of what was happening in the early 1970s, including the very important initiatives undertaken by the Extension Education Division under Fred Cachola’s visionary leadership. Among the programs was the Hawaiian Studies Institute.

Understandably, the Mitchell/Bowman piece does not explore the huge contextual importance of the Hawaiian Renaissance as the dynamic backdrop to the ’70s. Just a few highlights:

All of this not-withstanding, a Kamehameha honors student, Kēhau Abad, in the late seventies was still being advised not to take Hawaiian as it was not seen to enhance her academic prospects. Ironically, Kēhau had Sarah Quick Keahi as her homeroom teacher all four years of high school! She remembers wondering to herself even as a high school student: “What’s the background message here? That somehow it’s not a real culture and we weren’t a real people.” Shockingly, this practice of steering students away from Hawaiian continued into the early 1990s and is reported not infrequently to this day.

Nothing I can say in the time remaining could do justice to the tremendous contributions of Pinky Thompson. As you know only so well, his towering figure as a promoter of culture spans this whole period, casting the light of his many torches upon us, our school and indeed all who call Hawai‘i home.

As much as anyone, Pinky got us to look to the South Pacific, urging Hawaiians to honor their origins, their MAINland, as lying there rather than to the northeast. In the 1980s–90s, Kamehameha students and staff made many trips to the South Pacific, beginning in 1982 when Fred Cachola took Holoua Stender, Randie Fong and the Concert Glee Club to Western Sāmoa.

These trips were life altering for many of us, Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians alike, and not the least our students. Julian Ako notes that the 1991 trip to Roratonga and Tahiti was for him a first step on his Hawaiian language path, a journey that eventually would lead to two Hōkū Hanohano awards as composer of the year. These trips were a turning point for the institution in that profound changes occurred in our attitudes about our identity on campus and among KS leaders. Huliau!

Another initiative of great importance was in 1983 when a group of Hawaiian language teachers, including KS graduates Ilei Beniamina, Kauanoe Kamanā, No‘eau Warner, and Larry Kimura formed the ‘Aha Pūnana Leo which has played such a huge role in the renewal of Hawaiian language in the community at large and at Kamehameha. I should add that frustration over Kamehameha doing too little to reinvigorate and perpetuate the native language was in part what drove these people to do what has become their life’s work. Huliau!

Sarah’s description of Hawaiian being the orphan of the institution fits until well into the 1980s. In 1985, for example, only 10.7% of all language students were enrolled in Hawaiian, while 46% were choosing Japanese and the rest Spanish and French.

Enrollments in Hawaiian steadily and strongly rose in the next decade. New teachers were hired yearly as numbers climbed to peak in 1994–95 at 902 students enrolled or 60.2% of total language enrollments. Most of these new teachers, including Liana Honda, Keola Wong, Lilinoe Ka‘ahunui, Hailama Farden, Mele Pang, and Kalei A‘arona-Lorenzo, are KS graduates and former students of Sarah Keahi.

Teachers received support from Kamehameha to develop new curriculum and a kūpuna program was begun, with Kūpuna Elizabeth Kauahipaula, Bill Pānui and Violet Hughes visiting classes regularly.

Other important cultural initiatives of this period included the first steps taken toward the design of a Hawaiian Cultural Center, and the three series of year-long study groups entitled “Hawai‘i Kuauli,” designed by Kāwika Makanani.

The controversy of the late-nineties wreaked havoc on the Hawaiian language program. Spirits fell. Enrollments fell. Mandates from the majority trustees stipulated the teaching of “classic Hawaiian” only and forbade the use of the pepeke grammar system and the modern dictionary Mamaka Kaiao.

Hawaiian language teachers were defiant in defense of a program that they knew to be successful. They issued a statement saying they would not heed the orders from on high. Several Hawaiian language and culture teachers went on to play prominent roles in the teacher organization Nā Kumu and the founding of KSFA, the faculty union.

The strategic planning that followed the ouster/resignation of the former trustees in 1999, elevated ‘Ike Hawai‘i to a position of central and often-referred to stature in our school community. The words and the document ring hopeful. The actual deeds await.

CONCLUSION

On January 15, 2003, Gladys Brandt died. Her days spanned much of the history we have reviewed here. At the Bishop Memorial Chapel service celebrating her life, and following a bold performance of "‘Au‘a ‘Ia" before the altar, trustee Connie Lau referred to Kamehameha as a “Hawaiian school.” Hers was the first time that we had heard this absolute assertion at such an official moment of ceremony and reverence. At long last!

Earlier tonight, we saw Gladys Brandt as a child in shame, rubbing her skin with lemon juice. In our work tomorrow, let us not forget that image. Nor her words, quoted earlier, taken from a letter she wrote three months before her death:

“My father and mother, like virtually all Hawaiians at that time, wanted their children to succeed, and they believed that to do so required their children to adopt Western ways. Unfortunately, they thought this was possible only by leaving behind the Hawaiian language and culture. If they were alive today, they would feel differently. Like all of us, they were a product of their time.”

Those of us who now carry the responsibility for these days do indeed feel very differently. As Aunty Gladys said, we are products of our time. Yes. Yet while here, as Gladys Brandt also so wonderfully demonstrated in her life, we are called upon to use our days wisely and passionately to nudge, sometimes even thrust, our times nearer our dreams.

Our challenge to ourselves in this work of Ho‘ohawai‘i must be to probe our deepest sense of who we have been as a western school for Hawaiians, and ponder what we must now become, in these times, as a Hawaiian school.

Let us begin by asserting unambiguously that by the genealogy of our Princess, by the mana of our royal land base, by the backgrounds of our students, and by the bright light of those who have held high this culture, we are a Hawaiian school. This is a fact forever. This fact is indisputable and non-negotiable. We need no longer discuss it. We must instead locate together our new meaning, and from this meaning create that which most honors these deepest insights. Our task today is about destination; more importantly for Kamehameha, it is about destiny.

Let our work be strong and joyous! It is far from dark within. Kū ka lau lama! Forever standing amongst us are those many cultural leaders who have preceded us—heroes sung and unsung: Pauahi, Theodore Richards, Lydia Aholo, Frank Midkiff, John Wise, Kilolani Mitchell, Mary Kawena Pūku‘i, Winona Beamer, Midge Mossman, Gladys Brandt, Sarah Quick Keahi, Pinky Thompson and others.

These are the beloved kūpuna of our meeting here this weekend. In their times at Kamehameha, and like you this evening, they were students, teachers, administrators, and trustees. More importantly, more lastingly, they were keepers of culture. As the lasting cultural leaders of our story, they are here tonight as sure as you and I.

You, the cultural leaders of these times, seize the mana! Take their light and their aloha, their hurt and their hope, their care and their courage and thrust this Hawaiian institution forward as they have done before us! Huliau!

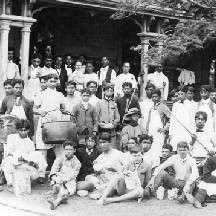

Hui ‘Ōiwi, 1941: "Oh yeah, everybody wanted to join. It was a real good club." (Roy Benham)

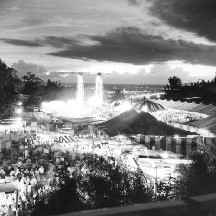

Newly-formed Hawaiian Ensemble students practice for first Hō‘ike in which standing hula was allowed: Song Contest 1966.

"The Hawaiian Show at the 1965 Karnival. The girls here remain kneeling, in compliance with KS policy. In their final dance, ʻKaulana Nā Pua’, they will stand up—a first at Kamehameha."