Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Hōkū Akana [Ka‘iwakīloumoku]

December 2012

Designated in 2006, the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument is setting a higher standard of accountability to Native Hawaiian communities regarding integration of traditional knowledge into resource management. The federal headquarters of Papahānaumokuākea is within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (ONMS), who works alongside six other governmental agencies to co-manage the Monument. Agencies who partner in this effort include the National Marine Fishery Service, also within NOAA; two offices within the U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service—National Wildlife Refuges and Ecological Services; and two offices within the State of Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources—Department of Forestry and Agriculture and Department of Aquatic Resources; and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Together, these offices collaboratively manage the third largest marine protected areas in the world.

The responsibility to properly manage Papahānaumokuākea lies with all collaborating partners. Because of this approach, conversations arise concerning practices that consider the combined dynamics of cultural, economic, governance, and enforcement issues. In these discussions, the offices work together to employ best practices and make decisions on how to apply the knowledge of kūpuna to decision-making.

According to Keoni Kuoha, what makes proper management of Papahānaumokuākea so important to Hawaiʻi is that the physical areas and living organisms of the Northwestern Hawaiian islands have cultural and genealogical ties to our traditional histories. Keoni believes that the larger vision for the Monument won’t work unless each of the seven agencies listed above recognize how Hawaiian knowledge and practice fit into conservation and management of protected areas. He reminds us of the cultural belief that Hawaiians are genealogically related to the ecosystems, the plants and animals, and the islands themselves.

“. . . and when we go to the NWHI, these things can still be seen in the wild—relatively unchanged by humans. Beyond the wao akua-nature of this place, for Hawaiian communities, having this unique place that is all of ours and none of ours at the same time allows a conversation that wouldn’t be able to happen otherwise.”

This new strategy in leadership is expected to help guide the planning, thinking process, and over-all work at the Monument. Recently, the Monument office began collaborating with the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) to gather feedback from Native Hawaiian communities to help develop what is currently being called the Native Hawaiian Research Plan (the Plan). The Plan is focused on how managing agencies can understand and support Native Hawaiian research at Papahānaumokuākea. However, putting the Plan together comes with some challenges. According to Keoni, Native Hawaiians have a healthy distrust of the word “research,” as native peoples have often been the object of that research. Additionally, Keoni states that research as it’s commonly practiced “hasn’t connected with how many Hawaiians relate to the world around us.” However, he also believes that this Plan also presents an opportunity to open up the concept and practice of research and imbue it with some really powerful Hawaiian approaches to understanding the world around us:

“The Native Hawaiian Research Plan is intended to help direct funding and program development for Papahānaumokuākea in the next three to five years. The Plan implements approaches that engage all senses in data acquisition, approaches that weave humankind into the fabric of nature and see purposeful relationships among all things, approaches that value the spiritual and emotional alongside the physical and intellectual.”

Those who manage other national marine protected areas have approached Papahānaumokuākea for advice and support. With similar goals in mind, Chilean officials have approached the Monument office to help them to develop a large-scale marine protected area around some islands that have long been utilized by the people of Rapanui—a place called Motu Motirohiva. The Cook Islands have also approached the Monument with this goal, since they plan to establish an expansive protected area that might encompass their whole Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). An EEZ is a sea-zone prescribed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea over which a state has special rights over the exploration and use of marine resources, including energy production from water and wind.

Through management practices employed at the Monument office, native communities are able to contribute to discussions on international policies that direct how nations perceive and deal with the ocean. With more and more of these large-scale marine protected areas seeking guidance and incorporating an importance of native culture into the resource management of these places, Keoni foresees a growth in sustainability where native cultural perspectives are integrated into national management practices.

This approach to thinking about ʻāina and natural resources at Papahānaumokuākea has already begun to trickle down to the community level here in Hawaiʻi. Various national and international levels of biophysical research conducted at Papahānaumokuākea can range from understanding corals, coral bleaching, and reef ecosystems to discovering new species of fish and developing long-term baseline knowledge of what is happening in that part of our archipelago. Efforts are being made through programs at the University of Hawaiʻi to work through this cycle of thinking from a community perspective which involves considering the cultural lens of kānaka. Within this process, researchers gather and express ‘ike in ways that make it more relevant to the Hawaiian community. As an example, research taking place across the archipelago with ‘opihi utilizes data found from research conducted through Papahānaumokuākea and cross-references with ʻike on the topic found in our communities. This is an example of communities, cultural practitioners, and scientists—many of whom are Hawaiians— working together to understand something of importance to us all. The findings will help governments be more sustainable in how various species across our islands are managed, while aligning policy to native cultural beliefs and practices. This shift in philosophy explores how natural and cultural resources can be balanced and managed using cultural knowledge as a core process. Keoni states, “Our kūpuna didn’t separate the fish in the ocean from the fact that it is a food source, part of our material culture, connected to them through genealogy, and linked to the survival of future generations. “

Although, Papahānaumokuākea is still learning how to integrate culture into everything that is done, what is key is to have decision-makers who recognize the value of bringing cultural ideas and practices into resource management. It also encourages communities to be engaged and share their time and/or expertise for the betterment a place.

Keoni states, “Beside those two critical ingredients, it’s certainly helpful to have Hawaiians in the organization with the ability to meld traditional knowledge with a whole array of disciplines that are a part of resource management. It takes some ‘eleu people to do that, but it’s not necessarily only about having degrees—it’s about having the knowledge, skills, and desire to make things (cultural sustainability) happen.”

Papahānaumokuākea started out as a small idea, some place. Since its inception, the idea of Papahānaumokuākea has grown to become a federally funded, multi-dimensional program where culture is a core foundation of their office’s policymaking strategies. Culture is a key consideration when discussing the area’s impact as a physical space that is a scientific, natural, and socio-cultural resource to several communities. This very old but still relatively new idea of cultural reflection is central to how the officials at Papahānaumokuākea will make decisions regarding international resource management, on a daily basis. The Monument’s initiative towards native cultural approaches of resource management will continue to be a model for other native communities and governing bodies to do the same.

“When we get right down to the core of what is happening, we can understand that it isn’t a new idea. It’s actually built on some very old ways of being—Hawaiian kūpuna did it for thousands of years. It’s what enabled our kūpuna to survive, and the blueprint for how they did it is there in our culture and history.”

In closing, Keoni shared this thought, “Culture has evolved over millennia to enable our survival up until this point; maybe it has a place in the sustainability of our societies hereafter, as well.”

photo courtesy of: NOAA

The reef systems of Papahānaumokuākea are home to numerous sea creatures.

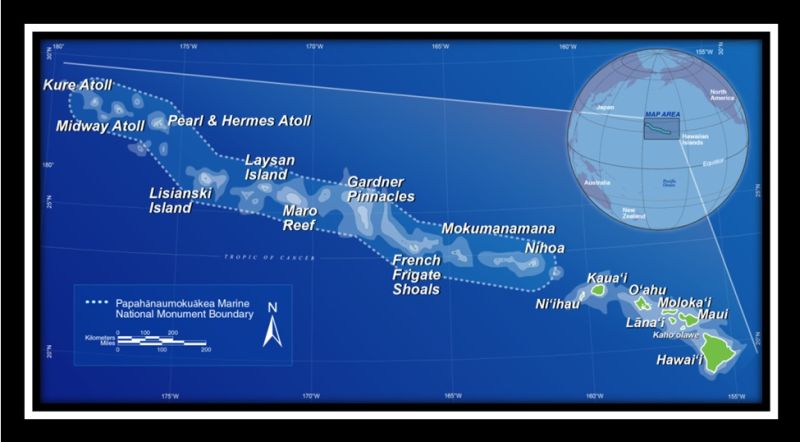

photo courtesy of: NOAA

Papahānaumokuākea is a natural, as well as, culturally protected area that encompasses the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) and almost 140,000 square miles of ocean.

photo courtesy of: Keoni Kuoha

Keoni Kuoha, graduate of Kamehameha Schools, works in the office of Papahānaumokuākea.

photo courtesy of: NOAA

The pristine reefs within Papahānaumokuākea are home to an entire eco-culture that is special to many native cultures.

photo courtesy of: Keoni Kuoha