Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Melehina Groves, interviewer [Ka‘iwakīloumoku]

October 2006

Hone Kouka has ancestral ties to Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kahungunu and Ngāti Raukawa. He was born in Balclutha in 1968 and raised in Rangiora, the pōtiki of a large whānau. In Dunedin, he attended King’s High School and Otago University, graduating in 1988 with a Bachelor Of Arts in English. In that year he also co-ordinated the first production of John Broughton’s Te Hara – The Sin. He went on to study in Wellington at Te Kura Toi Whakaari o Aotearoa—The New Zealand Drama School, graduating in 1990. Although Hone is best-known for his excellence as a playwright, he is currently the Development Executive for the New Zealand Film Commission, he writes for television, has acted as a script advisor, and has recently finished his first novel. He has won a string of New Zealand’s most prestigious playwriting awards, including three Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards. Since his Writer In Residency at Canterbury University in 1996, he lectures in Māori Theatre on an annual basis.

Hone and and the cast of The Prophet visited Kamehameha Schools Kapālama in late October and conducted a series of workshops for students and teachers. In this interview, Hone shares with Ka‘iwakīloumoku his insight on writing and personal expression—how his work is meant to teach and to inspire, not merely to entertain.

For information on obtaining some of Hone’s works, please visit huia.co.nz

MG: When did you write your first play?

HK: My first play I wrote in 1990, Mauri Tu. Honestly, I don’t do much theatre anymore, so it’s a real treat for me when I can. The plays are meant to be interchangeable, for example there was a production of Home Fires done in Gettysburg, South Africa. The plays are really designed for people to be able to take out the Māori component and insert their own culture. With The Prophet, I could very much see it being done here in Hawai‘i, with a Hawaiian cultural component. There are so many similarities, you know, just like us, but different. A lot of my plays are designed especially for Polynesian cultures to just insert their own cultural component in.

I got a chance to see the one done in Africa, and I was blown away, wow, you know, it really does work! Although, Home Fires is mostly images, so it translated really well. I also saw one done in Portugal, they translated the whole play into Portuguese. I feel I’ve been really privileged to have been a part of all this, to have my plays done around the world.

MG: You actually wrote The Prophet very quickly, how did that come so fast, yet have so many ideas interwoven so well together?

HK: Well, I really thought about the play for two years before actually writing it. And really it all started with the music. All the music in the play is hip hop and roots music, and that reflects this explosion that has taken place in New Zealand recently, just an explosion these days of that type of music. It’s unique to have a play revolving around basketball, I love basketball, I was raised with it, it’s physical and it builds momentum throughout the play. But really it’s more than just basketball. I took what I loved and put it in a story, much like you folks could do with something that ties you to this place, hula, wa‘a, you know? Things you love are always a great place to start.

So I thought about it for two years, and then I wrote for four days. The play is very much based on my whānau, and except for the Maia character, I used real names and characters of people in my own whānau. I always try to show my family in my plays, people seem to really like that. I’m a lot younger than my older brothers and sisters, the youngest of nine kids, so I got the opportunity to spend a lot of time with my nieces and nephews. A lot of my inspiration comes from my own family, how we watch out for each other and help each other, that’s what we were raised to do above anything else, that’s what we as a people are about, I believe.

It’s an interesting thing, because Pākeha writers will see a play like The Prophet and take it from a teen suicide angle, but Polynesians will come from a whānau angle . . . what a thing like suicide does to the entire whānau, how they cope and survive. Culturally, we see it differently, how does a family survive? And I didn’t want the focus of the play to be on suicide . . . there is a high rate of teen suicide in Aotearoa, but I didn’t want that to be my focus, you know? The Prophet was crafted to help parents pull kids up, kind of like Aunty Kay’s character tries to do throughout the play. Throughout the play, she tries to lighten them up once, twice, three times, and then finally it worked when she brought something up about their parents, something kind of funny and embarrassing for them.

Maia’s character really comes from the fact that there are so many strong women in our cultures, and in that one particular scene, she really used the book Andrew Beautiful’s character was reading to get him to open up, she prompted him. That one speech is the key to the whole play, and part of its power is you don’t really hear Andrew speak at all, leading up to that part, you know, he’s kind of quiet. You don’t hear him until he goes deep and it’s intense, like, wow! The audience loves it.

Another part of that speech speaks to how people, the larger community, view Māori in a negative way, and there was a lot in the media while I was working on The Prophet that painted most of us in a negative light, but it’s not true at all. A lot of what’s put out about Māori is negative, and I wanted to say something about that. Andrew’s speech addresses that and, really, that’s my voice speaking right there. That whole speech is just me. It’s very powerful, and that’s always my favorite part of the play. Mark (Ruka) delivers it so perfectly. And everyone listens to him, because here’s the youngest kid out of them speaking on this intense subject, you know? The whole play is based around the idea of love and caring for each other. That’s one of the reasons I wrote the play, to show the compassion that we are capable of feeling as a people.

MG: You mentioned that all of your plays can be compared to music, could you explain that a little bit?

HK: Well, Waiora was big, the play itself was just big in scope, and I was listening to a lot of classical symphonies, which are also very big and intense. Waiora is set at the time when my parents’ and their generation moved to cities and to the South Island, and the play itself is very naturalistic and impressionistic, it reflects this big theme. As far as the writing process, a year before writing Waiora, my father passed away. Our father would have gone so far for us, you know, he would have gone to the underworld for us. So in the play, a man really does go to the underworld to save his child, it’s such a big concept that the music that goes with it has to be equally “big.”

Home Fires, the second play in the trilogy, is more image-filled, more sequences that involve just movement. It’s almost closer to dance, but it had a very definite script, set to modernistic music. Home Fires is partly about two siblings, one of them is dead and comes for the other one… it’s set almost in a limbo sense, between worlds. And The Prophet is really like a pop or hip hop song. The Prophet has a really young vibe, the sequences go just like the type of music does, pow-pow-pow, just like basketball. I tend to write a lot like that. Actually, I’m writing a feature film now that refers to the novel that Andrew Beautiful is reading in The Prophet. It’s all intertwined together.

MG: What are you spending most of your time doing now?

HK: Well, I’m the Development Executive for the New Zealand Film Commission, so basically I get to help up and coming writers, young writers. I help develop them, I really want lots of them to have that experience that I had. I want to expose new writers to what’s out there, show them what they can really do with acting.

What’s great with The Prophet is that there’s always a character someone can relate to. As a matter of fact, I actually watched The Breakfast Club about four or so times while I was working on The Prophet, thinking, “Well that works really well, why does it work so well?” You know, they’re all family. The Prophet is about family and how you can’t choose them. One thing you can’t change is family, your cousins, you know, they’ll always be your family. It’s like when Laura tells Ty in the play, after he says there’s no way he could be a part of this family, “Don’t pretend, just be proud.”

MG: Throughout the play, there were quick changes in the emotion and intensity between the characters, were there any challenges that arose as you all prepared?

HK: The cast, they’re all fantastic professionals. A great example of how they can play off each other and work the dynamic is the “banter” scene—one line changes the whole dynamic of the scene. And it works every single time. As soon as Matt said that one line, the whole crowd went quiet. Same thing as the urupā (cemetery) scene, straight after the haka, you know as a writer, right after a part like the haka that is so intense, everyone wants release, so it works very well. You throw in something comedic, and they laugh even harder because it relieves the intensity. Writing that change dynamic is just . . . it’s so amazing to see it work. Sitting in the audience, I could feel it happening. I think it’s a combination of experience on both sides, on mine as a writer and theirs as a seasoned team of actors. It’s very much a group team effort. I just give them the ingredients, they take that and go with it.

MG: Could you go through a “day in the life” preparing for a play?

HK: Well, we like to work as a team, that team dynamic is obviously important in a play like The Prophet. We play a lot of sports, we’re always working together and cooperating. I also know that the actors are professionals and will deliver, but because this is an ensemble piece, they all have to work well as a unit, not just individually.

So, we’ll generally start with a cup of tea and go real hard till lunch, then have our lunch break. I don’t like to rehearse for very long periods of time, we do talk about the work but not that much, because it’s not all in their heads. As a people, we’re very physical so the physical parts help to work things out. One of the actors also talked about how it’s very important for us to eat together—work on the floor is kapu, we’ll karakia first, and it kind of puts the work on a different pedestal. Plus when people are full, they’ll work better.

MG: The actors were phenomenal, just so believable in the characters they were portraying.

HK: I actually wrote the parts of “Aunty Kay” and “Laura” for Tanea (Heke) and Waimihi (Hotere). And, really, all of these actors are out of their teens, so I’d also love to see real teens take The Prophet and act it out, I’d love to see how they interpret it. I can’t wait for the time when I get that call about high schools wanting to do my plays, when I get that invitation.

And with a play like The Prophet, you don’t need a lot of flashy props to get the audience involved and engaged. When we’re touring, you have to keep it simple, but that’s another reason I love theatre, it forces you to engage the imagination of the audience. It’s about painting pictures, you’re making human sculptures, creating images.

My inspiration for The Prophet . . . well, while I was touring with Waiora up the East Coast (of Aotearoa) with my mother, we got the call that one of my cousin’s kids—who was only 14 and very much like the prophet himself—had taken his own life. He had been very bright, very successful in school, and the family had put a lot of pressure on him. We tend to look to the ones who are successful, the few who are succeeding, and try to overcompensate for all the negativity by putting everything on this one person who is succeeding. Nobody saw it coming . . . and the whole family, you know . . . it made me realize that we should all take the lead in our families and communities. He was only 14, but you forgot how old he was. In a way, the whole family kind of felt like we did this to that boy, with the pressure and the hopes and all of that kind of thing.

So my mom, she was the one who told me, “You have to do something about this,” it was my job as a storyteller to do something about it, to articulate what had happened. That’s where the idea for The Prophet came from. The Prophet is set in my great-grandparents’ village . . . it’s really personal for me. And I think throughout the play, there’s this idea that comes through of how you shouldn’t take yourself too seriously, you’re not that flash . . . share your gift.

The play is about teens, but really it’s for their parents to watch. I’m really keen to have parents hear the voices of their teens, not just hear, but listen. A lot of times, parents don’t listen to their kids, to what they’re saying, but their thoughts are valid . . . they might not be able to articulate them so well, but the thoughts are there. Parents can see what their kids are up to, but they never really saw why they were doing what they were doing.

Take the character of Matt, for example, he’s like a lot of boys, he doesn’t talk a lot, but he’s focused on sports, or basketball in his case. When I was young, I’d play ball to get my frustrations out. Other guys especially can relate to that, to articulating in that way, and I wanted to write a young male character who didn’t need to talk to get his feelings and frustrations out. We all deal with things differently, Matt’s character lets his aggression out through basketball. Matt doesn’t talk a lot, but when he does, they listen. Laura she just talks and talks . . . Ty, he couldn’t release it, he didn’t have that one thing that the others had, but he needed to release it. That’s why he fought coming back to the village to face all of that.

MG: When you were starting out with acting and writing, or working with cultural things, have you ever been asked the question “How are you going to use that in the ʻreal world’?”

HK: Oh yeah . . . well, my daughter’s first language is Māori. She’s bicultural and bilingual—she can see the world through different eyes. She also speaks Sāmoan, Japanese . . . even if someone argued one particular language was more practical, she’s still learning to see the sun from another angle. That’s a very powerful thing. She travels with me a lot, cultural exchange is so valuable, and when we went to the Festival of Pacific Arts held in New Caledonia, she was only about four years old. One day while we were there, she met a Kanak, a young boy, and you could see what she did, her thought process . . . She went through all her languages, first she tried Māori, nope that didn’t work, so then Sāmoan, just went down the line, you know, and then she just shrugged her shoulders, and they went off and played [laughing]! She’s equipped with all of these amazing tools. Most of our problems come from a lack of understanding, and she can see, “Oh, you do it like that, but we do it like this, but really, we’re doing the same thing.”

Also, I think that whatever makes you strong is a good thing—why are there those people who feel like they have to put it down? If learning the culture makes you strong, then go for it. A lot of Māori kids are very self-confident, although we all have a lot to work on, it’s good because they learn that making mistakes is OK, don’t be afraid to put yourself out there, because it’s OK. That’s part of the reason that at the end of The Prophet, in Aunty Kay’s speech at the tangi, she acknowledges that Ty has a burden that he’ll always carry, something that will always be with him. You have to acknowledge those mistakes, your mistakes, or if not you’ll do it again, and they’ll just fester.

MG: Seems like people can really take something away from this play, and it makes not only culture but theatre viable to a larger audience.

HK: Right, right. Like in the urupā scene, those kids know they have a culture, but they don’t know exactly what to do, what the protocols are that they should follow there. They’ve seen people doing it before, but can’t quite remember . . . like the karakia for instance. Matt’s character is the most knowledgeable, he has the protocols, and they always look to him for “something Māori,” but at that point in time, he doesn’t want to speak. That scene is also speaking to the parents, to say to them, hey, at least they’re trying, at least our kids are trying. They might not be perfect, they might make mistakes, but it’s when they stop trying that we have a problem. A lot of our kids are like that, they know they’re supposed to do something, it’s in them, and we just need to let them know it’s OK to bring it out, even if that means making a mistake along the way. I think as Polynesians, there are things we just instinctively do, little things that we somehow know we’re supposed to do when the time arises, memories of things we don’t even know we’ve done.

The urupā scene really encapsulates that idea, that behavior we instinctively follow in certain situations or environments. Like Matt’s character, he was a favorite of their grandpa, so he naturally sat down with his grandpa at his marker . . . that koro who he loved so much, Matt knows his koro would have asked him, “What are you doing behaving this way?” The kids as a group know that in these situations, there’s supposed to be a speech, first a speech comes, then a waiata. They become more confident without even trying or knowing it, one thing just naturally follows the other until Matt’s character does a haka. He wasn’t willing before, but all of it just flows . . . The haka is also really a challenge to Ty’s character, the oldest of them, who also wasn’t doing anything. Challenging Ty to take up the leadership, and then at the end asking Joshua, “Why? Why did you go? We need you so much.”

That particular haka was really interesting, because the man who wrote it for the play knew Matt’s character had asthma, so his breathing would change throughout the haka as he got short on breath. So he choreographed specific breathing parts and sounds into the haka, the composer really knew how this character worked.

MG: Someone asked if your plays are an attempt to bridge urban and traditional Māori culture, to bridge the two for modern youth. Do you think that’s the case?

HK: Well, a lot us live in urban centers, you don’t have to accept it or put it on, but as an artist, I try to move it forward. A lot of our kids . . . they know they have a culture, they sort of know what to do, they know there are things they’re supposed to do, but they aren’t quite sure what they are. Like the urupā scene. For me, it’s not really about marrying the two—“urban” and “traditional”—together, but because you don’t want to break the tikanga, the rules, you just have to be smarter about how you talk about them. It’s about sticking to tradition but allowing the expression to be theatrical and work in a play, again the urupā scene is a good example.

When I was growing up, I was one of three Māori in my school. It wasn’t until I went to university that I found a place where culture could flourish, up to that point, my family had kept the culture alive in my life. In my work, we always follow the tīpunas’ advice, I’ll go to them and ask, “Can I do that?” They’ll tell me, “No, but you can do this.” We always go with that guidance.

MG: Have you toured with The Prophet anywhere besides Aotearoa and Hawai‘i?

HK: No, so far we’ve only toured home and Hawai‘i, and I felt it had to come to Hawai‘i first. I wanted this play to go to Polynesia because of the experience I had touring with Waiora, and I wanted to bring it back.

MG: A lot of audience members were wondering about the reason for naming the cow “Nelson Mandela.” Was there any significance?

HK: [laughing] Well, when I was growing up, my mom had a horse named Tarzan, I’m not sure where it came from, but it was just kind of a thing to give animals these strange names, so I thought, “Well, Nelson Mandela would be great.” There’s nothing really profound behind the choice of name, but the characters see the cow as a toku, a sign, sort of a presence that occurs.

MG: Do you have any projects in the works?

HK: Well, the next play that I’m writing—and really, I don’t get to do much theatre anymore so it’s such a treat when I do—was inspired by something that happened at a Christening I attended. At this child’s Christening, one of the uncles stood up you know, looked around, and asked, “What’s happened to all of you? Where have you all gone?” And I knew exactly what he was thinking, what he was talking about. In Aotearoa, we have this huge middle class that has become very successful Christians, but they’re losing their Māoriness. When all the family comes together, they look around and wonder, what’s happened to all of us? It kind of ties in to what you asked about earlier, you know, when people ask us why we taught our daughter Māori, because we want to open her up and allow her to see things from that point of view.

Writing is a good thing, it’s a great thing and everyone does it in one way or another, whether they realize it or not. No one can tell your stories, and the more you practice, the better you get. I consider myself to be a good craftsperson, even if I’m not the best, I’ve learned that people want to know what you have to say.

I find I can get really hoha with the world, you know, and writing pieces like Andrew Beautiful’s speech . . . those kinds of opportunities to make a statement about the world are what drive me as a writer. I feel like, “We’ve got to do something about that!”

photo credit: Michael Young

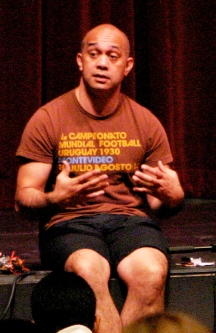

Hone Kouka, at a series of forums held at the Princess Ruth Ke‘elikōlani Auditorium at Kamehameha Schools Kapālama. Cast members participated in forums throughout the day for nearly 600 students and staff, answering questions and providing insight into the play, The Prophet.

photo credit: Michael Young

photo credit: Michael Young

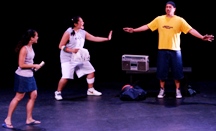

Cast members Miriama McDowell (Maia), left, and Tanea Heke (Aunty Kay).

photo credit: Michael Young

Cast members, from left, Jarrod Rawiri (Matt), Waimihi Hotere (Laura), Taungaroa Emile (Ty), Mark Ruka (Andrew Beautiful), and Miriama McDowell (Maia).

photo credit: Michael Young

Andrew Beautiful’s speech was a pivotal moment of the play.

photo credit: Michael Young

An image from the urupā, or cemetary scene, which Hone feels works so well because of the dynamic changes in emotion: ". . . In the urupā (cemetery) scene, right after a part like the haka that is so intense, everyone wants release, so it works very well. You throw in something comedic, and they laugh even harder because it relieves the intensity. It’s so amazing to see it work. Sitting in the audience, I could feel it happening."