Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Randie Fong, interviewer [Ka‘iwakīloumoku]

April 2004

Māori Actor Rawiri Paratene gained international acclaim for his role in the movie Whale Rider. Paratene visited Kamehameha Schools in April of 2004 to discuss the movie and the various cultural themes featured in the movie.

Randie: Describe for us what kind of impact has the film had on the indigenous Māori population?

Rawiri: It works both ways because the indigenous Māori population has had an impact on the film as well. I think that from the minute that the film started to be produced there was a feeling that it was going to be received quite well from around the world. I mean that. The Māori population took guardianship over the story, particularly the home people. The Māori population is suspicious of media and with good cause. The media hasn’t really stood us in good stead over the years and still doesn’t. The image of the news media in New Zealand; for example, the papers and the news stories feature Māori stories a good deal. I’ll give you an example. I’m a documentary maker as well and I wanted to make a documentary which looked at the re-ruralization of Māori. Through the 1960s the Māori were shifted out of their rural homesteads into urban home lands and in the 80s and 90s lots of young Māori families decided to take their families back to those rural homelands. I wanted to make a documentary about children whose parents had chosen to raise them in the country areas again. The focus would be on how successful they are and how-well adjusted they are because they are growing up in their own culture more than they would if they had grown up in the city. Also, when they leave school they go to wherever they are going to go and they get employment straight away; they graduate and they are high achievers. The head of the channel where I was pitching the documentary said ‘Rawiri it’s just too positive. I don’t know if anyone wants to watch a feel-good story like that.’ He’s looking me in the eye and I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe he was being so honest with his response.

Māori were suspicious of the film as well. They saw it as a real challenge. The success of the film has laid down what we call a whale, a challenge, to Māori film makers to follow up on that success. Once Were Warriors was the second most successful New Zealand made film and before Whale Rider was the most successful New Zealand made film. We’ve had quite a successful film-making industry in New Zealand. The two films that have managed to reach international audiences of any significance have both been casts of Māori and Māori stories; both of them. We’ve made a great many films that are from other parts of our culture as well. However, the two stories that have met with international success have both been Māori stories. So, that lays down a real challenge to Māori. Both of those stories were produced by haole, we call them pakeha, the true ownership of the product is not with Māori. Once Were Warriors was written by a Māori,and the script was written by a Māori, by Riwia Brown, and directed by Lee Tamahori. Nikki Carro [the director of Whale Rider] is a European New Zealander.

These are real challenges; we want to take even more ownership of our stories. We have been arguing with the powers that be, that our stories are of international interest and our stories are the most internationally intriguing to come out of New Zealand. Whale Rider and Once Were Warriors has proven that. That lays a challenge for us to take even more ownership of the telling of our stories. Mostly the effect the film has had on the Māori population the Maori people, they are just so proud of this movie. So proud that our stories are valued enough to be received by you here today. Last month I was in Germany and I was received there and speaking to groups where two people cried. They saw it in Germany and I’ve been all over the United States and Australia and Britain and all over the world and the Māoris have taken ownership of it. That’s the real thicket of it.

Randie: When Māori youth, especially those who live in Auckland, they may not be in touch with their traditional homeland and they go to a mall and they stumble into a theatre, what do you think is happening? What message is there for young urban Māori to see their traditional stories up on the big screen?

Rawiri: I wish my son was here now. The message that I’m getting back from them and it reiterates to, you know our youth are constantly being challenged. We’ve done pretty well over the last 30 years at reasserting our pride and we’ve made some great steps. There is such a strong pull away from one’s own culture. There is a strong pull for us to have one culture. Wear the same labels, to go into the same looking malls, to eat the same food, to speak the same language. Your government hopes for the same accent, and the English governmentt hopes for the same accent as well.

There is a real move toward, with globalization and all of these things, to let go of what makes you special. I know that when the Māori kids see this film they just go ‘Yeah Keisha’s a Māori girl. She grew up in a very ordinary suburb in Auckland. She goes to Penn Rose High School and she’s been to Hollywood and Hollywood flocked to her. I’m a Māori girl and I can do it too.’

They go to it and they see a story that is based in a mythology that often the western world seems to have a problem with mythology. They call it myth, we call these stories history. They refer to the Paikea tale as mythology. The fact of the matter is, an ancestor arrived over a mass of water with a whale and that is the fact. The western world chooses to call that mythology because they find it hard to believe. Yet, I’m denigrating it at all, we just came out of a period where somebody rose from the dead. I don’t deny that, I don’t deny that at all. I’m never going to call that mythology. I’m never ever going to call someone else’s history mythology. But our history is presented as myth. That’s the same for the Vietnamese, their stories are simple. The same for the Hawaiians, the sun people in Norway. Indigenous stories are minimalized and are really tried not to take seriously. Then, out comes a story like Whale Rider which is an unashamedly spiritual story. Which deals with a miracle and people are like ‘yeah that can happen!’ They watch the first five minutes of this film, they are a contractor who drives an earth moving machine, has been dragged into a cinema by their wives for the first time in 25 years, they are horrified with the price of popcorn because the last time they went into a cinema it cost them $.05 for a bag now it costs $10.00, they are in a grumpy mode, it’s a chick flick anyways, it’s about a little girl and a whale for God’s sake. They are watching this movie and they signed a contract with the screen and they have said okay I’ll sit here with my $5.00 popcorn and let you do this. They do. It happens. I’ve seen it happen. In cinemas all over the world I’ve sat in the back and watched these big men who, by the end of it, have allowed themselves to be taken on an emotional journey into a world that they don’t even understand the language of and yet they have understood everything that it is about because it gets them in here. That’s what the film does to the kids back home too, it gets them in here. Of course it has an extra special meaning for them because it’s about them.

Randie: I have talked with a couple of colleagues who have recognized that everyone comes away with a different message as to what the movie is about. For you, what are some of the critical messages of this movie?

Rawiri: My younger son saw the movie and he came away and said ‘You know there are 16 animals in that movie apart from the whale? There were four cats and so many dogs and some kittens.’ I said ‘Oh, did you enjoy the story?’ For him the whole movie was about all the other little animals that walked across the road or sat on the fence. I think that any piece of art the message is one of the beholder, so I’m not going to distract from whatever the messages you might have. For me as an actor when I was working on it I saw the piece as a message on leadership. I needed to explore leadership very, very carefully and I think the film does that. By the end of making the movie I discovered lots of things about leadership. I discovered that it’s something that is being reexamined by us all. We have very traditional understandings of the roles of leaders and who we chose or who is born or who we have met or whoever becomes the leader who bullies themselves to become the leader. These are the things that this film deals with. I’ve discovered that these are very important things for right now. There are a great many world leaders who I hope would see this film. Because, as the person who played the traditional leader, the tyrannical leader, the straight down the middle I’m not going to bend, the stanch hard leader, as someone who was going to have to explore all of those qualities, and I’ve explored it fully. I’ve discovered that one of the most essential qualities of leadership is humility.

There’s one point in the film which is a key moment for me. It’s when I look out to sea and the granddaughter is out on the whale. When we filmed it of course there is no granddaughter on a whale. It’s just the sea and the horizon. The reaction in my eye has to be real. Nikki Carro, the director, comes up to me and says ‘This is probably the most humble moment in your life.’ The word humble had not been a part of my thinking in terms of my portrayal. I just went away from that and I went away from the camera and everyone was down there and I was watching the crew and they were all walking and this was my close up. This was the telling shot of my character in the whole movie. I walked away and I looked out and I saw the crew. I looked at the whole village and I saw the village and I looked at all of the people that were playing the extras, the locals there. I looked at everyone and they were just there waiting for me to be ready to do this shot. I had been shocked by the direction and I just needed a moment just to sit there. All I did was look. I suddenly realized that in a moment I’d walk back down and everyone’s focus was going to be around that frame. In the center of that frame was going to be me. Everyone’s expertise, hard-work, goodwill and heart, everything for that moment was going to be to make me look good. I felt humbled by that. I didn’t have to act. I just went down there and just stood there and just let them shoot. That was take one and then Nikki came up to me and said, ‘I think we got that Rawiri. We’re going to move on.’ I knew they had it because I did exactly what the essence of leadership was.

The essence of leadership is humility. It’s very easy for the leader to get into a position to forget that. It’s the hardest thing when you are in control of something to let go, to let go of that control. But, always know that the moment that you let go of it is actually the most powerful moment you’ll ever have. That is easier said than down. Some of you in this room right now are leaders or are being groomed as leaders or are grooming leaders. Leaders are essential. We need to totally reexamine our whole way of thinking in terms of what is leadership. Not just gender bases and age bases; which is what the film concentrates on. Every single angle of it has to be examined. The challenges are huge but anyone who is involved in leadership can learn from humility. I assure them that their leadership will be true, honest and powerful. I know this because of that little moment in film. At that moment that character’s life, which was the most humble moment of his life, had let go and that was when he could see the truth.

Randie: I understand that there was a well done Shakespeare play in Maori. Tell us a little bit about that and where Māori are headed in terms of theatre and literature?

Rawiri: It’s a feature film called The Maori Merchant of Venice. It’s based on a very old translation by one of the great Māori academics and one of the great Māori leaders of the 20th century Dr. Pei Te Hirinui. Produced and directed by one of the elders of our modern film industry Don Selwyn. Not a great many people in New Zealand saw the movie but it is becoming a very famous movie indeed. It’s The Merchant of Venice translated into classical old Māori. It’s probably available on DVD. It was a real ground-breaking piece. It won the Hawai‘i Film Festival in 2002. I shouldn’t really start talking about Shakespeare because I’m a real buff.

Randie: Well, the question arises, why, why would one translate Shakespeare into Maori? For what purpose?

Rawiri: You know when I was given this role Koro my reaction was, I’ve just been asked to play King Lear. I was being asked to play someone who was blind. I was being asked to play somebody who had a deep love for his role. A person who treats his role with the utmost respect. Shakespeare deals with epic themes like that and he deals with it by telling a story with a beginning a middle and an end. This is exactly how our ancestors deal with telling our histories; whether it be orally or by carving or in dance or in song, our stories are epic. Shakespeare and the Māori culture just goes hand in hand. Shakespeare is why I’m doing what I’m doing. I went to see a play. I went to see Hamlet. I was 14. I had never seen a live production in my life. I went to see it because I was going to be missing out on mathematics and also the Catholic girls were going to be there and I was going to be able to flirt with them. That was my agenda in going to the theatres that day. The experience changed my life. I sat there and I watched a play about a young man who was well-bred, whose elders were acting in a corrupt and disgusting manner, and he was the only person who knew about it. Everyone thought he was mad. I was 14,15,16 at the time and I’m sure if you think back to when you were that age everyone thought you were mad too. You were the only person who understood what truth was about. That play was about me. Our teacher tried to teach us Shakespeare out of a book for all that time. Meanwhile I went and saw him between two curtains and I thought that’s where it belongs, right! I’ll do that. And I’ve been doing it ever since.

Rawiri Paratene and Keisha Castle-Hughes.

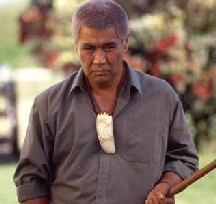

Rawiri Paratene.