Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Melehina Groves, interviewer [Ka‘iwakīloumoku]

November 2005

Lyonel Grant, Māori carver, sculptor, and designer, was an artist in residence for over two months at Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. He participated in the pilot exchange between The Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa (or Creative New Zealand/Te Waka Toi) and Hālau o Laka/Native Hawaiian Visual Arts Program. The goal of the Toi O‘ahu Residency program is to establish a relationship which provides cultural exchange and professional development opportunities for Māori and Hawaiian artists, while allowing the resident artist opportunities to network with Native Hawaiians and learn about our history, culture, and arts. Grant also shared his insights with many community groups on various islands, including devoting an entire day to presentations at the Kapālama Campus of the Kamehameha Schools.

The request for this pilot residency was to have a master carver who was firmly grounded in his culture but was able to work in a contemporary context. Says Maile Andrade, assistant professor at Kamakakūokalani, "We needed someone who could create and function in both worlds on a high level, representing his media as well as his people. We also need to raise our own skill level in this craft and encourage the next generation of carvers. Lyonel Grant was the perfect resident artist, inspiring our students as well as our community practitioners, and allowed us access to his world of Māori carving, design, and conceptually insightful ideas."

MG: Could you give us a little bit of background on yourself? How things got started?

LG: Well, where I trained was very classically orientated. There was no written component in the course and I was a graduate of honor at my graduation. At that time the master carver would fastidiously teach us his tribal style and it wasn’t the style from the area that I come from. In fact it wasn’t the tribal style where the carving school was situated, either. He was from Ngati Porou. The school’s in Rotorua, the heart of Te Arawa, and here we are learning Ngati Porou style or influenced work. But when you’re learning, you just latch on to anything you can to increase your skills.

What happened was I started to look around at our carving styles which, basically, my tutor wasn’t that impressed with. The stuff that he was referring to was stuff that was done in the ’20s and ’30s, when tourism was taking hold. A lot of work was being bashed out just for the tourists, and it was pretty basic, pretty raw. I can understand why he wasn’t totally impressed with it.

MG: This is your tribal area, Te Arawa?

LG: Yeah, Te Arawa. Te Arawa did have a strong carving tradition via a sub-group called Ngati Tarawhai and their work was impeccable. Every time you reference it, that’s so. But he never really said much about the Ngati Tarawhai style. It wasn’t until I actually left there that I really started to think, you know, well what are the benefits of our own tribal style, and then from that came the glaring observation, the glaring problem that I didn’t have my own style. I had great facsimiles of what the old people had left us; whatever style, whatever tribal group, I could copy it but in actual fact I didn’t have a voice of my own. It’s likened to what they call the Rodin Wall: anybody who works in sculpture figuratively will hit the Rodin Wall. It’s too wide to go around, too high to climb over, and you end up finding your place in respect to the so-called Rodin Wall.

So basically, for me, the work that the old people left was my Rodin Wall: too high to scramble over, too wide to go around. It took me 20 years carving to realize that I have to find my place in respect of the old masters. What that meant was how do I make myself carve differently? You know, I’ve been meticulously trained in those styles, how do I think beyond them?

What I decided to do was try different materials and limit my approach to creating things by shifting my emphasis on material. For example, if you have a piece of glass you can’t get a chisel and cut it. You can’t get an adze and adze it. So you’re confronted with a whole different set of problems on how to actually make something out of it. And you either jump in and embrace the material, make something and create a statement of what you want to make out of it, or you go scrambling back to the wood with your tail between your legs.

I started off with glass etching, creating patterns on glass, and sandblasting. That worked for a little while and then I had the chance to carve in Finland. So I went to Finland in ’88 or ’89 and carved over there for about ten days at this festival, this symposium. There I saw people working the same material as me in a whole different range of ways. For instance there was an older lady there, sweet old darling you know, and she was on this tall chair. She had this post and she had a little axe, and she just kept tapping away at the top of it . . . hello? [laughing]

All week she was there, she’d stop for a drink of water, go back to tapping. And we were just going, "Oh come on, what could she possibly be doing?" Anyway at the end of the thing, of course we’re carving like you wouldn’t believe, you know, flailing arms and all that, and then it came to the end of the week and they showed different peoples’ work, like an exhibition? The piece that she’d made was this face, a weathered face, on the end-grain of the timber, the end of the timber, all with axe-cut marks. A whole weathered face, it was really, really beautiful. So I went up and spoke to her, didn’t actually say sorry, ’cause she didn’t know that we’d been . . .

MG: [laughing] Right, why bring it up?

LG: But she . . . it was beautiful and it just made me realize you don’t need chisel and mallet; you can use a blow-torch, you can use power tools, you can use an axe. It’s not necessarily the tool, but just different people working the same material that I worked all my life in different ways. Different approaches. So you start . . . like somebody else cut their piece of wood up into slivers and then sewed them back together as a wall and then perforated the wall. So it wasn’t a solid piece of timber anymore. And of course the first thing that I’m gonna do is carve it; I’m gonna make a relief piece, three-dimensional piece out of it, and I’m working within the boundaries of the material in that regard. But other people say, "No, I’ll cut mine into tiny, tiny quarter-inch by quarter-inch strands and build this amazing tower out of it," and that was their approach.

So it really made me re-address what I was doing. At that time I met a sculptor from the UK and he invited me to his workshop on the way back to Aotearoa and he was casting bronze. I thought well, I’d like to have a go at that, so as soon as I got back to Aotearoa I started casting. Being involved in the process of casting, there’s no art per se in it, it’s all process. So being a process, you can get swallowed by the mystique of the procedure. Wow, furnaces burning to 1200 degrees, hot pouring metal, molten wax, the whole deal. And you get swept up in the process but there is little or no art in the process, it’s just a technique.

But being involved in it helped me create other works . . . for example, most of the larger commissions that I’ve done, I’ve had to make miniatures so I could present them to the client. Sometimes even a corporate gift. For example one such incident was when I made a little carving that had all the details, all the filigree on it, everything on it. Then I made a mold of it and from that mold I created a wax version of it ready to cast into bronze miniatures. One of those waxes had a lot of air bubbles in it so it wasn’t suitable to go right through to the bronze process so I put it back into the molten wax, pulled it out, and it was this sculpture, this amazing sculpture that was the essence of the original but it had gone back in. That was the piece that became a six-meter high, (twenty-foot high), bronze. So it was like serendipity, something that just happened, and it was superior to the original piece that I was considering. It just came.

Another one, I was pouring bronze and it came right up to the top of the cup, just getting ready to solidify and the mold broke! A lot of the metal ran out on to the ground, and I thought, well it’s road kill, you know, chucked it away. And then at the end of the day I went back to it and started chipping off some of the shell that is the mold, that holds the middle, and this piece came out that was perfect on one side and then it just blew out on the other side. It had this amazing mark. The ones at first that had come out all perfect, they stayed on the shelf and this other one was the one. Plus, there can only be one of those, because you can’t make another wax like it. So that’s interesting and you can only get that by doing the process. If I had handed it over to a foundry they would’ve scrapped that one. There is merit in knowing the process, but not falling prey to it.

All those little experiments led me to different forms and different things, yet there’s still a thing about making that statement . . . you go back to the classics in the museum and there’s a handful of pieces—20, 30, 40 pieces—and they’re all brilliant but there’s 30 stand-out pieces where you go, "Wow that’s so cutting-edge, that’s so amazing," that’s so whatever. Then if you were to get 30 modern pieces . . . I don’t think there is one seminal piece that stands out in the last, say, 40 years. I don’t think anybody . . . there’s some really great ones, but . . .

MG: Do people ever come up to you and ask, "What were you thinking doing that?" or question your pieces?

LG: No, not so much because there’s this watershed. On one side of the watershed is classical work for classical reasons with classical application, for the stereotype of the culture . . . we tend to do it ourselves and fall back into this tried-and-true imagery that works, that is accepted by everyone in sundry. The other part of the watershed is work that you do on your own volition, looking for that "what do I do" side of things, you know. So it’s an interesting thing and it seems that never the ’twain shall meet, they’re always going to be separatist movements.

What I’m trying to do . . . I need the integrity of that, one can’t exist without the other, I think. Maybe I’m the only one that thinks that but I don’t think so. You need to have the pedigree of the tradition in order to extend yourself, to give validity to any modern expressions you may have. I think that one validates the other. The trick is how do you escape the gravity of the classical and the classically oriented pieces, how do you escape the gravity of that to find new expression but to keep the energy the ihi and the wehi sort of like the life force, the mauri, the mana. How do you keep that but make a piece that’s totally different from those, totally different but related. It’s an age-old problem and I don’t think any one’s really hit it yet. I don’t think I have but that’s what I’m aiming to do. I don’t think I’ve achieved that yet.

My latest task, now that I’ve dabbled in other materials, stone, glass, bronze, aluminum, even margarine—you know hotel buffet sculptures—now my plan of attack is to bury myself in a classically-styled project, like the marae. Bury myself in the creation of ideas for that and re-inventing those ideas that I create for the marae, like that figure with the two faces coming together. That came from a solid idea that was specifically for the marae and yet it created a contemporary figure that is overtly Māori but not like any other figure that exists. That’s somewhere along the lines of where I want to go. I think it was Keone Nunes who said, "I see that piece as a Māori piece." You know the glass piece, he saw that as a Māori piece. He read it, more importantly, he read it as a Māori piece to me. It’s interesting that he sees that piece as a Māori piece and it doesn’t have one Māori scroll pattern on it. He still read it that way, and that’s what I’m after. So I’m looking for bigger and better things.

MG: Do you have a favorite material to work with?

LG: I guess I would enjoy returning to wood. Now that I’ve had some little excursions away from wood, I find it a lot easier to go back to it and not be so restricted or locked down in how you think and how you operate in wood.

MG: That whole issue of tradition and change is fascinating.

LG: Yeah, and I think you have to be versed in tradition before you change it. No other way, really. See, tradition is so strong it’s like a black hole, it drags you back into it. It’s so strong and the imagery is so . . . all encompassing.

MG: Do you feel like nothing changes?

LG: Well . . . if you want to be the worst critic, you could argue that. In the late 1950s, ’60s in Aotearoa, there was what they called an urban shift from the rural populations, the rural Māori populations shifted from a rural existence to an urban existence in droves. And they say it’s the biggest exodus of that kind, ever, per capita. So they all end up in the cities looking for work, thinking that’s the great hope. The children of those families now learn in urban educational systems, not the rural, close-knit type systems. You’ve got an eclectic mix of kids all thrown together, usually had a Pākehā teacher. They learned their art from European masters who’d learned their trade in Europe or were versed in European art history technique, ethos, whatever, and then apply it to their students.

So these Māori kids who are still speaking Māori, they’re getting taught by these Europeans. They’re taught trades by the Europeans and then they apply those tools of trade to the art pieces they make and view traditional works through those eyes. They don’t try to replicate because replication is boring, replication is tried, so they want to reinvent. So they wouldn’t be limited or feel obligated to be locked down or to stay in tradition. They weren’t victims of the tradition, they were the free spirits that could take anything they wanted from the tradition, manipulate it any way they wanted, for any outcome.

Then there was a separatist movement where you had the people who were trained master to pupil, master to pupil, master to pupil, trained in carving, let’s say, like I was. Of course the modernists are saying to us, "Oh, you guys are just imitators, not innovators. What you do is technique, it hasn’t moved since the masters left their pieces that we see in the museum. What do you do that’s different? You replicate things, you don’t innovate, there’s no innovative language in what you do, you’re simply a technician." Then the argument from outside, from the traditional side of things . . .

MG: You consider yourself a traditionalist?

LG: Well . . . that’s how I was trained. For argument’s sake I’m there, I’m playing the devil’s advocate. [laughing] We’d say, my tutor would say to the modernists, "Well who are you to take that particular design that means this and broadcast it all over this canvas saying it means something it doesn’t? It means this! You’ve just appropriated these things, who are you to appropriate this and use the mal-proportioned version of this beautiful traditional thing and do what you’ve done to it. Who are you to do that?"

I guess they were equally valid in their arguments. So, for quite a while, there was a separatist movement with the two sides running parallel to each other. But now in the ’90s there’s been more of a merging again of those things. Still an uneasy connection in a lot of ways. Not many carvers, not many traditionalists, can move over to the modernist sphere and there’s not many of the modernists’ sphere that can do the traditional. No one’s actually done it, you know, so maybe that’s one thing I’m trying to do. Move from that tradition over into pure sculpture, pure art, whatever. It’s been interesting. And the art is evolving as well, in both camps but it’s still sort of separate development in a lot of ways . . . art apartheid.

It happens in the performance arts, as well. A lot of the music that’s created for our performance arts has links back to the post-war era where popular tunes of the day were taken and Māori lyrics were put to them. The young people that were brought up with that sort of music around them are now the tutors of the modern groups and there is still an element of that . . . the melodies . . . have a very ’50s feel. But that’s being really . . . how do I put it . . . being really broad-brushed, that’s not always the case. And some of the younger people that are teaching take Stevie Wonder’s "For Your Love" and give it Māori lyrics. Possibly the worst application of that is a Māori album of Bob Marley songs. They sing it in Māori and the music is identical and the words are just totally translated. Which aren’t really Māori ideals or concepts.

MG: That just goes right back to the old "pua doesn’t equal flower" thing. We deal with the same things as you folks, with language, with hula, all of that.

LG: Yeah, so those kinds of songs don’t do much for me. Whether we’re further down the track in all that, I don’t know. Although, the other night we were on the Big Island and we went to Kamehameha Shopping Center. Down below it there’s a big hotel and there were a couple of ladies, maybe in their early sixties or a bit older. The band that was playing with them was a Hawaiian band, two elderly ladies playing ‘ukulele, guy playing bass, big guy playing guitar. Of course once they struck up a certain tune, these ladies would get up and go for it, hula, you know? They’ve still got it, still got the whole show-person thing and the right inflections with the hands and everything. No male’s safe in the room, they’re dragging people up and they don’t take "no" for an answer. And if you’re a klutz, you just make them look better! [laughing] Reminded me of my aunty back home—she still does Tina Turner impersonations, and she’s . . . 65? Tina Turner and the Tuatuas. Tuatua is a little shellfish. [laughing] And she’s still going for it, she’s the youngest 65-year-old in Rotorua. But then some of the old people shake their head and say, "Ohhh, look at them go."

MG: There’ll always be both sides, I guess.

LG: Yeah . . . but to make that amazing piece, I don’t know. I don’t know who will be the judge of that, you know, because you’re your own worst critic. I don’t think I’ll be able to do it while I’m criticizing what I do. There are some pieces that I do like, I’ve got probably three pieces that are sort of getting to where I want them to go. And then you look at them and think, "Well, what if this is as good as it gets?" You know? [laughing]

MG: If you feel like you get there, "it’s perfect," than you might stop pushing yourself.

LG: That’s true, too. [laughing]

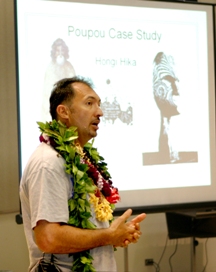

photo credit: Michael Young

Lyonel Grant offered several presentations for high school students at the Kapālama Campus of the Kamehameha Schools.

photo credit: Melehina Groves

"Waitūkei." This bronze sculpture was unveiled in 2001 to mark the new millennium and was inspired by the people of the Rotorua area and the rich melding of Māori and European cultures. It is located outside the Rotorua Museum of Art and History.

photo credit: Melehina Groves

From left to right, Lyonel Grant, Maile Andrade, Melehina Groves, and Layne Richards inside Pou Wairua at the Sky Casino in Tāmaki, Aotearoa.