Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Ho‘okahua Hawaiian Cultural Vibrancy Group

February 2014

February is Hawaiian Language Month! The Kamehameha Schools Hoʻokahua Cultural Vibrancy Division is commemorating the occasion by sharing a series of KSOnline articles. The following story looks at how Hawaiʻi’s native language is enjoying resurgence and growth.

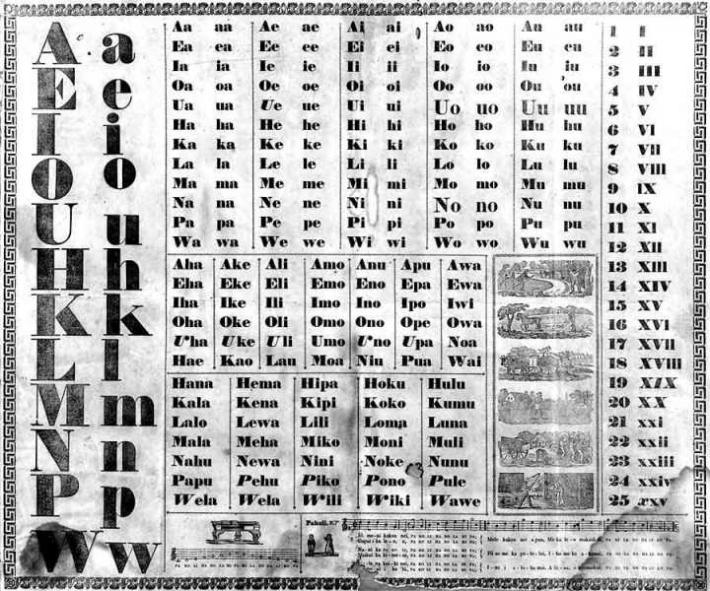

The Hawaiian language first appeared in writing in the 1820s. Incorporating ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) into the classroom was catalytic and transformative for Hawaiians, leading to national literacy rates topping 90 percent in 1835.

Much has happened in the 180 years since then, including the cataclysmic decline of Hawaiian language, only to be brought back from the brink of extinction.

Today we are enjoying an era of continued resurgence and growth for the Hawaiian language. Sparked by the Hawaiian renaissance of the 1970s and by the Hawaiian language immersion education movement of the 1980s, ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi is slowly being recognized in the wider community as an important part of life here in Hawaiʻi. Certainly, that’s how it should be—a native tongue should be valued and widely spoken in its homeland.

At the inception of the Pūnana Leo Hawaiian immersion preschool program in 1983, the number of speakers of Hawaiian was estimated at 1,500. In 2013, Gov. Neil Abercrombie’s proclamation of Hawaiian Language Month stated that there are an estimated 30,000 speakers of Hawaiian at “various levels of fluency,” but that the language is still endangered and will remain so until we reach critical mass.

This being said, we live in exciting times of change. The Kamehameha Schools ʻohana is working diligently to finalize the KS 2040 Strategic Vision and we have been asked to imagine what Hawaiian education could look like a generation from now.

So, where do we see ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi in 25 years? What needs to be done to make the language thrive? What do we see, hope, and plan for the future of our prized ‘ōlelo? And what are some key indicators of progress?

First and foremost, the government’s recognition, protection, and support for ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi are critical. ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi already has status as an official language of the state, yet the government seems to use Hawaiian language in decorative and superfluous ways.

The passage of House Bill 1984 sponsored by Sen. Kalani English would elevate ‘ōlelo Hawaiʻi to an actual language of the legislature once again, and not just for ceremonial use on the opening day.

Imagine the governor delivering a stirring, well-executed, state of the state address in Hawaiian. This would do much to bring prestige and power back to the language.

To no one’s surprise, much of the growth in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi has happened in classrooms, through educational programs, and in hālau hula. Through these efforts the number of speakers have grown, albeit gradually.

We have not yet reached the tipping point of general usage in Hawaiʻi. The community of speakers is still relatively small and homogeneous, predominantly consisting of ethnically Hawaiian speakers.

With the recent passing of State Board of Education policies that open up Hawaiian pathways of learning, we are poised to reconnect ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi and Hawaiian culture with education on a larger scale. This is yet another strategy in bringing our mother tongue back to a state of vibrancy.

It has been argued that, to some degree, every kanaka Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian person) should know their ʻōlelo makuahine (mother tongue). The perpetuation of knowledge and culture can be a part of a personal commitment to be part of the larger Hawaiian community.

For Hawaiians who do not speak ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, one helpful perspective might be that instead of thinking, “I don’t speak Hawaiian,” one simple addition could help create change—“I don’t speak Hawaiian YET.” And then, go and take advantage of the learning opportunities.

For individuals and communities to commit to speaking Hawaiian there has to be some incentive. For some, being an active participant in Hawaiian culture is its own reward—it is their chosen lifestyle. For others, it may help to have economic incentive.

Imagine if businesses or government agencies offered their services in Hawaiian. There would be an immediate need for skilled speakers and ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi would be seen as a valuable skill in the workplace. Here at KS, we don’t have to look too far to see a Hawaiian organization that is positioned to create more environments where ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi is valued and can thrive.

E ola mau ka ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi! Long live the Hawaiian language!

photo credit: Ka Ipu o Lono

Haumāna at Pūnana Leo o Waiʻanae listen to moʻolelo told in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi.

photo credit: Ka Ipu o Lono

Hawaiian immersion education, one of the most successful methods of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi learning, is key at schools like Ka ʻUmeke Kāʻeo.

photo credit: Ka Ipu o Lono

Kanaka Hawaiʻi in the 1820s quickly adopted the written version of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, leading to high levels of literacy by 1835.