Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kīhei de Silva

The authors of He Mele Aloha remind us that the practice of kanikapila, “play music,” was once a part of our daily lives—an informal gathering of family and friends on front porches and in back yards for the simple purpose of singing Hawaiian songs. Today, however, our music has moved from the home to the stage, from Uncle on an upturned milk crate to The Caz on DVD. “It has become something to listen to rather than participate in. There is a sense today that singing is reserved for those who are really good at it. Still, many people yearn to kanikapila.”

He Mele Aloha is a substantial, well-conceived songbook whose mission is nothing less than the return of kanikapila to its grassroots origins. The book is meant for those of us who know a lot of songs but can’t begin to remember all their Hawaiian words, let alone their meanings and origins. It is meant for those of us who can “dumb strum” an ‘ukulele but need a little help with chords and even more with transposing keys. It is meant for all of us irredeemable amateurs who yearn, despite our musical shortcomings, for the warm companionship and celebration of kanikapila.

The 267 songs in He Mele Aloha are arranged alphabetically from “Ā ‘Oia!” to “Yellow Ginger Lei.” Chord and transposition charts are provided at the beginning of the book, and pertinent chords are also diagramed at the top of each song. If you can’t remember the G, A7, and D7 necessary for “Kaulana ‘o Waimānalo,” they’re right there for you to copy. The text for each mele is given in Hawaiian and English, except, of course, for the 40 or so English-only songs included in the collection (Randy Farden Jr.’s “Beautiful Kaua‘i,” for example). Each song is followed by a brief explanation; in spite of their brevity, many offer valuable insights into the mele they address, as in the following write-up for “ʻAhulili”:

Scott Ha‘i, a cowboy from Kaupō Ranch, asks: “How come you go to that mountain and not to mine?” Word play, a favorite device in Hawaiian songs, occurs here with “lili,” which means jealous, and “ʻAhulili,” heaped up jealousy, a prominent peak in Kaupō, Maui, depicted as jealous because it is seldom covered by the light mist that typically settles on other mountain peaks. There are numerous versions of this traditional song about a jealous woman. A slightly different, older version has these additional lines: “E ō ‘ia e ka lei, Ke ‘ala kūpaoa, Ka puana ho‘i a ka moe, Ka beauty o Mauna Hape.” Respond, oh garland, the powerful perfume, my dream it is, the beauty of Mount Happy.

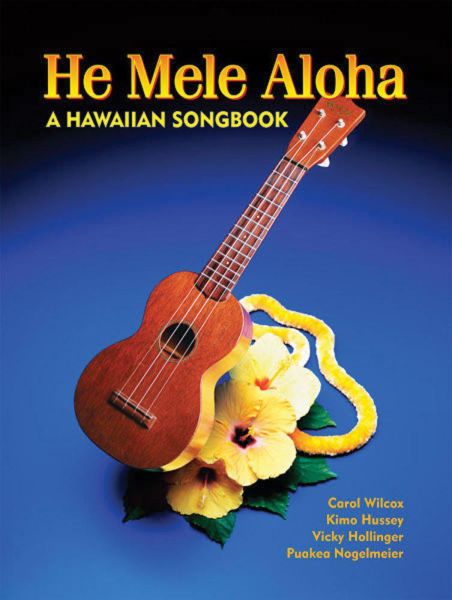

Because Carol Wilcox, the prime mover of He Mele Aloha, had the good sense to assemble a top-notch team of collaborators, their collective effort is a model of accuracy and unpretentious good taste. Vicky Hollinger and Kimo Hussey were responsible for chording the songs. Puakea Nogelmeier edited the Hawaiian texts and English translations; where necessary, he also provided new translations of his own. All in all, one feels secure when working with this book.

Secure in the sense that it has been carefully compiled and produced. Secure, too, in the sense that it isn’t likely to fall off a knee, milk crate, or music stand: the book is wire-bound; it opens flat; it stays put at whatever page you’ve opened it to.

And if this isn’t enough to recommend the book, He Mele Aloha is also an entirely charitable production: profits from its sale go to Lunalilo Home. He keu kēia a hana ka lokomaikaʻi.