Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Camille Naluai

Here in Hawai‘i it’s common to run into relatives. Even upon meeting someone for the first time a short discussion can reveal that you and your new acquaintance are cousins. The next time you run into one of those relatives take note; they could have valuable information regarding your family tree.

Fran McFarland of the Family History Center in Lā‘ie is a genealogy whiz. With a few clicks of a computer mouse she can find some of the most obscure relatives.

“Oh! That’s an early date,” she says with excitement as we begin researching my family name only to discover a relative who was born late in the 1700s.

With the help of an online research tool,familysearch.org, McFarland and I begin working on my maiden name, Naluai.

The search reveals 140 living and deceased relatives.

I was lucky. With McFarland by my side the research process turned out to be a breeze. But, for most people, searching for your family roots can be a difficult process.

“Too many people get started in a tangent and start with someone else like their aunty or uncle,” said Rhoda Kalua‘i who, with the help of McFarland, holds regular workshops at ‘Iolani Palace helping people begin their genealogy search.

Daphne Lowe is the director of The Family History Centers of Hawai‘i. The centers are operated by the Mormon Church and are available to anyone, free of charge. The church website houses over 40 million names.

“We have centers on all the islands, even on Moloka‘i,” Lowe said.

Lowe, McFarland and Kalua‘i make it a point of letting people know, right off the bat, that they do not do the research for those who come into the centers.

“We just help people get started and how to find the clues,” McFarland said.

For some people merely going to the workshop proves to be all you need to do to find the information you seek.

“One of the people who signed up for the class was trying to locate a missing family member and they had this really unusual last name,” said Keola Cabacungan of ‘Iolani Palace who oversees the event.

Cabacungan said another person with the same unusual name had already signed up for the class. That was interesting, he thought. He decided to inform the two of the situation.

“They met and found out that they were looking for each other,” Cabacungan said.

For Native Hawaiians documentation of your family roots is vital if you plan to attend Kamehameha Schools, apply for homestead land, or pursue any of the other programs and entitlements available to Native Hawaiians.

During McFarland and Kalua‘i’s most recent workshop the majority of the 2 dozen people who were in attendance were Hawaiian.

“If you don’t know yourself then you can’t get started,” Kalua‘i told the group.

First, McFarland and Kalua‘i recommend starting with what you know and working your way backwards.

The problems begin when you realize; you don’t know much.

Historically Native Hawaiians were taught their genealogy through chant. The hiapo, or first child, was given to the paternal or maternal grandparents, depending on the baby’s gender. It was the child’s job to learn the oli of their family’s genealogy and ‘aumākua. The child was given to their kūpuna to insure the family’s history would be accurate as the generations grew.

Following western contact and the outlawing of the Hawaiian language the practice of chant was almost lost. Today, most Hawaiians can not recite their Hawaiian genealogy.

So, Native Hawaiians must look to early documents that may shed some light on the family blood line.

In 1830 the first Hawai‘i census report was conducted.

“Anything after that is when you have to start talking to your family,” McFarland said.

If you can’t find your family on that census report it doesn’t mean that they weren’t here. McFarland says early census takers did not travel the entire island to get an official count. In all likelihood the actual count of Native Hawaiians may be much greater than the census states.

“They just did censuses on those who were part of the church, or were near to where they were. They didn’t get here, to Lā‘ie, for several more years,” McFarland said.

The next census was taken in 1860. This time, census takers decided to ask for surnames, something Native Hawaiians did not have prior to 1860.

“We never had surnames. We were just, whatever our name was, and that was it,” McFarland explains.

For Native Hawaiians a name was a valuable possession. A name possessed cosmic energy that, when spoken, was capable of influencing the health and well-being on the bearer of that name.

So, McFarland says, when census takers asked for last names most were not willing to compromise their cultural beliefs.

“What happened was that if a guy had 12 sons they would break up their father’s name. Now they all have different last names but they’re all brothers,” she said.

Both of those censuses are housed in the State Archives. According to McFarland the History Centers have the same information available to them as well.

Hawaiian last names are sometime spelled wrong within families. Two people might be related but because of differences in spelling don’t realize that they are. Fortunately, some online research tools can scan names that may sound similar, helping find as many potential relatives as possible.

Getting Started

You’ll need to get a family pedigree chart. You can get one from any of the Family History Centers.

Several sites offer pedigree charts as well, free of charge.

http://www.smartdraw.com

http://www.ancestry.com

www.familysearch.org

“There is so much information out there that we aren’t utilizing,” said Kalua‘i.

Research Required

Although genealogy websites are growing at a rapid pace you may discover that not all the information you need is available on the web. If not, you may be able to find the information you need by using the following list as a guidline.

Census Records: The earliest census record was taken in 1830. This document as well as any other document before 1900 is located in the State Archives. Anything after 1900 can be found in the state library.

Cemetery: The importance of tombstones is sometimes overlooked by people doing a genealogy search. The marker often gives a person’s name, date of birth and death.

Newspaper articles: Clip out newspaper articles family members are in Kalua‘i says. Marriage announcements, obituaries and athletic achievements are just a few documents that may be useful to a family researcher. Make sure to write down where that article came from and what date the article was published.

Courthouses: Courthouse documents are especially useful in land disputes.

Family Photo Albums and Journals: “Some families have books of their genealogy; they just don’t know they have them,” said Kalua‘i.

Military Records: The military releases information regarding its enlisted personnel every couple of decades. According to Kalua‘i the latest records available at this time are from the 1930s.

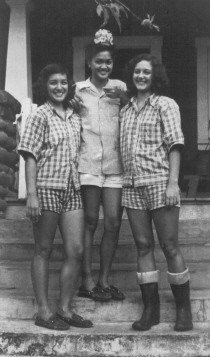

Granddaughters of Henry Kekuewa and Annie Pahukula: Lani Pratt, Momi Low, and Lorna Pratt (Kona, 1946). Research at the Family History Center in Lāʻie has helped present-day members of the Robert Clark Pratt family to trace their ancestry to Keaweikekahialiiokamoku, ruling chief of Hawaiʻi in 1720–1740.

To start, you’ll need a pedigree chart. Charts vary in styles from the tree shaped chart to a diagram like the one above.