Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Today when we say "talk-story" we often mean it in the diminished sense of "shoot the breeze," "chew the fat," "chitchat." For the most part, the talk-story of our day is informal, spontaneous, and of little consequence—a field of weeds in which a few flowers might haphazardly bloom. Eddie Kamae, however, belongs to a generation for whom talk-story is an art form characterized by the same dignity, delight, and intellectual rigor as that of haku mele, of song writing. More often than not, when Kamae and his generation talk-story, their easy informality is the pinch of ‘inaʻi by which a carefully concocted dose of wisdom is administered to a listener’s naʻau. These stories are rooted in experience, but many are shaped by hindsight, by telling and retelling, into set pieces that deliver lessons, describe turning points, and testify to the presence of the divine in our quotidian lives. These stories, like songs, are saved, practiced, retold, and assembled into repertories from which the story teller draws when engaged in ‘ai kole maka onaona—in eating the sweet-eyed kole fish, in telling delicious stories. Most of this story-telling generation is gone, but the now-grown kids and grandkids who listened in at the kolekole table, will tell you that there was as much nourishment in talk-story as there was in a carefully prepared meal, as much kaona in Tūtū Man’s narrative as in his carefully composed mele.

It’s been more than twenty years since I first talked story with Eddie Kamae. He was at the Dillingham Jack in the Box, alone, and the place, at mid-morning, was otherwise empty. Māpu and I recognized him immediately, so we sat quietly on the opposite side of the room: close enough to be respectful; far enough away to be respectful. There is a certain distance to keep, an orbit to maintain, when you are makaʻāinana in the presence of aliʻi.

But Eddie, who is the epitome of ʻōpūaliʻi, looked up, smiled, and came over to talk-story. His truck was next door at Firestone; he was waiting for his tires to be changed. Yes, he knew Māpu; he had given her permission, several years earlier to choreograph "Mauna Kea," the first verse of which he had learned in Kalapana from ʻOlu Konanui. And yes, he recognized me from the Bishop Museum Archives where we often worked, white-gloved, turning crumbly mele-manuscript pages with those flat metal chopsticks. We talked a little bit about Elia, a mystery composer whose identity continues to haunt us. We talked a little bit about one of my favorite songs, "Sweet Hāhā ʻAi a ka Manu," and Eddie shared a little bit about his search for the song’s complete lyrics. He was hoping, he said, to spend time with an old, Kauaʻi man named Godwin or Goodwin who rode a bicycle with a mandolin strapped to his back. Gabby had tagged along on Eddie’s last trip to Kauaʻi and the old timers were too awed by the Pahinui presence for Eddie to get them into a sharing mood.

And then Eddie told us, in considerable detail, about his visit to Nāhiku, Maui, where he had expected to meet with David Kahoʻokele, a ninety-five-year-old canoe-maker who wanted to talk-story. "I put the trip off for a while because I had too many other things to do," Eddie said, "so when I finally made it to Maui, I learned that I had arrived on the day of this man’s funeral." At the funeral parlor, after whispering his apologies into Kahoʻokele’s coffin, Eddie was greeted by a young man who quietly told him, "My grandfather was waiting for you; he tried to hang on until you came."

Eddie told me the David Kahoʻokele story again, eight years ago, after a Sons’ mini-concert in the Bishop Musuem’s great hall. He told it as a preface to a story about Kawena Pukui sending him to Maui to see if a "Hawaiian woman with a Spanish sounding last name" would share the song "Huelo" with him. He did, in fact, find this woman, and not in a funeral parlor. She lived in a pink house and carried a bag of Durham tobacco. She rolled a cigarette, put it in her mouth, and offered him the bag. He declined politely, waited quietly, and—i ka wa kūpono—asked if she might have a song for him. Yes, she did, and it came with a little background: it was about a Huelo minister who was originally from Kauaʻi. One day his work took him to Keʻanae where he met a woman, and they "went off together." "When I heard that," Eddie said, "I knew what the song was about. It was a love song. All the best songs are."

Eddie told me the Kahoʻokele story again, five months ago, at an ʻAha Pūnana Leo benefit dinner honoring Nākila Steele. This time, he told it as a preface to the story of "Ke Ala a ka Jeep." He talked about going to South Point, Kaʻū, with Kawena and Willie Meinecke to revisit the storied places of Kawena’s childhood: Waikapuna, Pāʻula, Puhiʻula, Kaulana, Palahemo. "Puhiʻula—that’s the cave where Kawena and her grandmother stayed in the summer when they collected salt and dried the fish that one of their ʻohana brought to them." The trip, he said, had inspired the jeep-song and helped him to understand what Kawena had said earlier about his true work being "out there." He had heard from Nākila’s daughter Pualani that Māpu was interested in making a dance for "Ke Ala a ka Jeep"; maybe we should go to Ka Lae with him and visit those places first.

These are the only three times that I’ve talked story with Eddie: at Jack in the Box, under the Bishop Museum whale, and at Nākila’s dinner. Three chance meetings at eight year intervals over the course of a quarter century. Three tellings of the Kahoʻokele story, each providing a necessary, almost formulaic prelude to other stories that he wanted to share. Aunty Maiki Aiu Lake was fond of saying, "Three visits to the dentist don’t make you a dentist"; three talks with Eddie Kamae don’t make me an Eddie Kamae expert. Still, I cannot help but advance a hypothesis: the Kahoʻokele punch line, "My grandfather was waiting for you, he tried to hang on until you came," is Eddie’s bottom line; it’s what he can’t let happen again. It’s an epiphany—a moment of intense, spirit-zapping realization—that he refuses to put away. It marks a turning point in Eddie’s life, his transformation from captain ʻukulele to keeper of culture, from entertainer to educator, from virtuoso to visionary, from makaʻāinana to aliʻi.

Eddie, of course, doesn’t tell you this stuff. He just tells you the story, delivers his ‘inaʻi-laced dose of wisdom, and leaves you, if you’re so inclined, to build your own sermon around it. I flatter myself to think that maybe he saves this story for listeners he deems receptive; maybe he’s tried—three times in a row now—to light the fire of fear and inspiration under my own equivocating ʻēlemu.

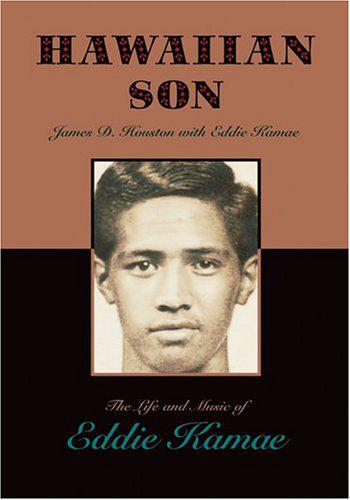

Mine is certainly not the only posterior deserving of Kamae’s flame, so it comes as no surprise to me that the David Kahoʻokele story occupies a prominent place in James Houston’s biography, Hawaiian Son: The Life and Music of Eddie Kamae. Because Houston takes us through this life in chronological fashion, Kahoʻokele comes up at mid-point in the narrative, but its impact—at least, for me—is no less pervasive or foundation-setting than if it had opened the book. This story of failure is paired with one of success: Eddie’s discovery of Sam Liʻa, his spiritual father, the violin-man of Waipiʻo Valley. Eddie parks his jeep, walks across the lawn and up the stairs of a Kukuihaele cottage. A white-haired elder waits on the porch in a straight-backed chair; he wears a necktie and black suit. When Eddie introduces himself, Tūtū-Man Liʻa answers in Hawaiian, "I know; I’ve been expecting you." The two stories, funeral parlor and front porch, epitomize the heartbreak and triumph of Hawaiian Son, the low point without which the high cannot be appreciated, the negative and positive terminals of the battery by which Eddie has been powered, for more than thirty years now, in his quest to record and share the old, true voices of our kūpuna. If not now, never.

Eddie’s teacher, Mary Kawena Pukui, probably would have identified these episodes as each having two parts: hōʻailona and hōʻike, sign and revelation. According to Tūtū Kawena, the hōʻailona most often originates with a guardian spirit. It is sent to approve, instruct, or warn. If the recipient is open to such messages, the hōʻailona can elicit the "awesome, emotion-charged, flash of knowledge" defined as hōʻike. The two usually work together, "sign stimulates revelation, hōʻailona brings about hōʻike" (Nānā i ke Kumu, v1:53–55). Thus does the voice of Kahoʻokele’s grandson come to Eddie from someplace beyond with a warning that shakes the soul. Thus does Sam Liʻa’s prescient greeting come from that same ancestral "beyond" with an affirmation that empowers the soul. Thus does the hōʻailona of Kawena’s own coffin, rolling back and forth under Eddie’s hands, trigger the revelation: hoʻomau, hoʻomau; carry on. "I knew then that she was still speaking to me, telling me what to do right to the end. Finish the work. That’s what she was saying. Finish it."

Kawena tells us that Hawaiian families of old treated their stories of signs and revelations "like heirlooms," passing them from generation to generation with the same reverence that accompanies the handing down, from mother to daughter, of tūtū’s lei hulu and quilts. Perhaps the most extraordinary gift of the many gifts shared with us in Hawaiian Son is that Eddie treats us like family—he carefully hands over to us his personal treasury of hōʻailona and hōʻike. Hawaiian Son, humbly disguised as talk-story, is, in fact, a meticulously crafted lei of unfading epiphanies, one after the next, all sewn on the cord of never and now.

These epiphanies provide us with a map of Eddie’s spiritual growth—of his gradual awakening to the voices of kūpuna seen and unseen, and of the manner in which these initially enigmatic communications have come to infuse his life with direction, passion, and purpose. Eddie doesn’t do this to show off; his show-off days, his captain ʻukelele days are long gone, washed away by Kahoʻokele and Liʻa. He is motivated, instead, by the ʻōpūaliʻi of his ancestors, by an ʻōpū filled with aloha. Edward Leilani Kamae has fashioned a lei lani of epiphanies for us to wear in hopes that, wearing it, we will learn to draw inspiration and guidance from that which he has learned to trust.

There is much talk today—and considerable pooh-poohing—of something called "Hawaiian world view." We who advance this concept are often asked to list, in western analytical fashion, the defining characteristics of this decidedly non-western view. We might do well to say that it is embedded in the talk-story of our elders, and that there is no better single, hold-it-in-one-hand expression of this world view as that told, talk-story style, in Hawaiian Son.

Nīnau: A pehea ke kolekole ʻana?

Pane: Hū ka ʻono.