RAPA NUI

Learn More About

‘Iorana! — Aloha! ‘Aha Moananuiākea honors the strong cultural relationships between Kānaka Maoli, Native Hawaiians, and the Mā‘ohi, the indigenous people of Rapa Nui, which includes a shared love of our lands and waters, our peoples, our languages, and our identities. Learners of all ages and backgrounds are invited to immerse in this rich Pacific heritage and explore topics of interest at a self- directed pace. Māuru-uru! — Mahalo!

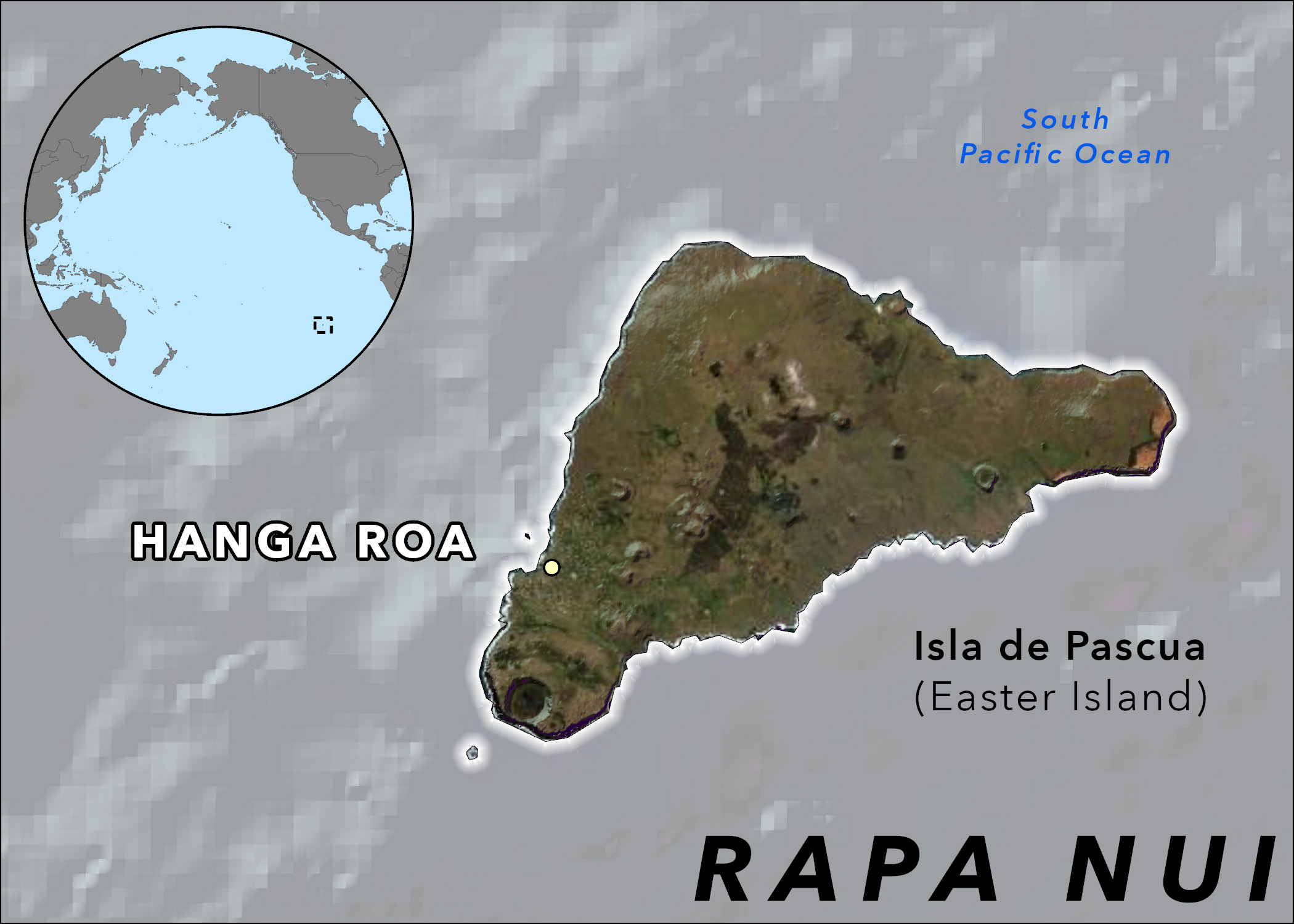

Rapa Nui is an island located in the southeastern Pacific Ocean. It lies 2,182 miles (3,512 km) west of Chile and 1,289 miles (2,075 km) east of Pitcairn Island, and is considered one of the most geographically remote locations on Earth. It is a volcanic island created by a hot spot situated on the Easter tectonic plate between the Nazca and Pacific plates. The island is 14 miles (23 km) long by 6.8 miles wide (11 km) and has an area of 63.2 square miles (163.6 sq km). The highest peak, Maʻunga Terevaka, rises 1,663 feet (507 m) above sea level. Hanga Roa is the name of the main town and harbor area where the majority of the population resides. Two traditional names for Rapa Nui are Te Pito o Te Henua, translated as “the center/navel of the world” or “the end of the land,” and Mata- ki-te-rangi meaning “eyes gazing skyward.”

Historical accounts indicate that the name Rapa Nui came into use in the mid-19th century. To distinguish it from the considerably smaller island of Rapa in the Austral Islands over 2,000 miles away, the Polynesian word nui meaning “big” or “great” was added to form Rapa Nui; this suggests that the island of Rapa Nui may have formerly been referred to as Rapa.

Likewise, the Polynesian word iti meaning “small” was added to the name of the island in the Australs, which became Rapa Iti. Unfortunately, the two otherwise unrelated island communities both fell victim to the Peruvian Slave Trade of the 1860s; and it was likely under these nefarious circumstances that a distinction between Rapa Nui in the southeastern Pacific, and Rapa Iti in the south central Pacific needed to be made. A popular spelling convention today has the geographic location represented by two words, Rapa Nui; and the people, language and culture represented by one word, Rapanui. Indigenous Rapanui people also refer to themselves as māʻohi, or native – though it is uncertain if this is a traditional Rapanui term, or Tahitian, which accounts for a high number of borrowed vocabulary.

The Land Of Hotu Matu‘a

According to oral traditions, Rapa Nui was first discovered by the navigator-chief, Hotu Matu‘a who landed at Anakena on the north-northeast end of the island. Radiocarbon dates from archaeological assemblages at Anakena show evidence of early occupation between 980 AD and 1280 AD. Social organization during the early settlement period consisted of extended family units governed by heads and elders of households. Hotu Matuʻa, then, would not only have been the leader of the extended family of founding voyagers, but the chiefly progenitor of the numerous clans that would develop over generations. The relatively small number of founding families would have made landfall amidst tens of thousands of seabirds and land birds, and surveyed a heavily forested island landscape thickly blanketed with a very useful variety of palm tree. This three-century window for early Rapa Nui settlement is consistent with dates for Mangareva and the Marquesas, the two nearest island communities and likely homelands of the Rapanui people. In fact, late first millennium to early second millennium settlement dates – 900 AD to 1100 AD -- show consistently throughout East Polynesia (including Tahiti, Tuamotu, and Hawai‘i) as a period of robust dispersal, settlement, and voyaging interchange.

Negotiating Power And Governance From The Ahu

Integration of archaeology and oral traditions reveals a four-century horizon for the rise and decline of large scale production of megalithic statuary and architecture from 1100 AD to 1500 AD. The resource-rich environment which early settlers took full advantage of, led to a significant increase in the population. Typically, more people require more resources, and acquiring control over those resources creates political tension; this was the social backdrop for the manufacture of ancestral stone figures called moai. They were carved from basalt extracted from the Rano Raraku quarry, transported to various destinations across the island, and erected on stone mounds called ahu. The dimensions of these giant images has drawn many to theorize on exactly how the colossal statues of ancestor-chiefs were transported, or “walked” to their locations, as described in traditional stories. Such feats of engineering would have required a sizeable working citizenry which some researchers estimate to be at least 10,000 people. Thus, management of people, resources and prestige, or mana, evolved from simple family leadership to a more complex, stratified system led by the authoritarian chiefly class – the hereditary elite.

After several centuries of predation by early settlers, bird populations decreased dramatically causing islanders to turn to other sources of protein. The clearing of forests for agriculture, wood for daily use, and to provide logs for moai transport (according to some sources) were long considered the main contributors to environmental degradation. There is now strong evidence that the Polynesian rat which fed mainly on the seeds of the once prevalent native palm was a significant factor in deforestation, which resulted in the depletion of a wide range of critical resources on which the population of some 10,000 people depended for survival.

Huri Moai: The Overturning Of The Moai

1500 AD to 1722 AD marks a period referred to as Huri Moai – the overturning of the moai. Rapa Nui’s hereditary chiefly class of ariki – or what some researchers call the “Ancestor Cult” – began to deteriorate, eventually buckling under the pressures of intertribal raiding and pervasive warfare. The importance of the moai diminished, and the weakened hereditary elite had no choice but to relinquish governance to the warrior class, the matatoa. This monumental shift in society led to the end of moai production, and the emergence of small carvings called moai kavakava which depicted the figure of a male ancestor with cadaverous features: an emaciated body, protruding ribs, sunken eyes, and long-hanging ear lobes, etc. While sources differ on the meaning of these prolific carvings, there is general agreement that they symbolize the decline of ancestor veneration, and possibly the widespread starvation as a result of overpopulation and societal trauma. The matatoa-led society of warriors that surfaced seemed to abandon not only the ancestors but much of the pantheon of pan-Polynesian deities.

Emerging to fill the political vacuum was a new governance paradigm and religious order centered around fertility and the creator-god named Makemake. Commonly depicted in Rapanui petroglyph art as a face with large eyes, or a skull with large eye sockets, Makemake became the patron god of the Tangata Manu, the Birdman Cult. Each of the island’s clan leaders would select a young able-bodied warrior-athlete to participate in a high-stakes, death-defying relay. At the start of Spring, competitors gathered at Orongo, a seasonal ceremonial village made up of a series of low, circular rock wall enclosures with sod-covered roofs, perched on a sea-facing precipice at Rano Kau crater. Their task was to wait for the return of the Manutara, the sooty tern, then descend down the sheer cliffs of Orongo and swim out past Motu Iti to Motu Nui islet with the help of reed water floats called pora. Their quest was to retrieve the first Manutara egg of the season on Motu Nui, swim back to shore, climb up the cliff and present their fragile treasure for all to see. The winner of the relay would become the tangata manu, the bird man, making the representative clan leader the paramount chief of Rapa Nui for the next year. This new governance process continued to the 1860s when missionaries put an end to the practice.

Rapa Nui's Position In The Pacific In A Globally Connected World

18th century European imperialism and expansionism in the Pacific left no islands untouched. Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen happened upon Rapa Nui on Easter morning, 1722, hence the widely-used Western name “Easter Island.” Nearly fifty years later in 1772, Spanish captain, Don Felipe Gonzalez de Ahedo arrived with two ships and documented having seen moai standing upright. In 1774, when British explorer, Captain James Cook landed in Rapa Nui, he noted that some moai had been toppled. Cook was able to communicate with the native population through one of his Tahitian advisers, Hitihiti. Then just two years later in 1776, French Admiral La Perouse anchored in the harbor of Hanga Roa and drew detailed maps of the harbor and the island.

By mid 19th century, the native population had significantly declined to some 3,000. In the aftermath of Peruvian blackbirding (with about half the population taken away against their will to serve as slaves in Peru and its territories), the rampant spread of tuberculosis and small pox (which was exacerbated by slave trafficking at various Pacific ports), and the forced relocation of Rapa Nui’s people to Mangareva and Tahiti, resulted in the traumatic depopulation of Rapanui natives to 111 persons by 1877. Rapa Nui was annexed by Chile in 1888, and the remaining residents were confined to the settlement at Hanga Roa with the rest of the island being rented out to the Williamson-Balfour Company for the raising of sheep until 1953.

Chilean citizenship was finally granted to residents of Rapa Nui in 1966, and the island was designated a “special territory” giving it constitutional status. In 2017, about 7,750 Rapa Nui residents were registered in the Chilean census, of whom 45% (3,512) identified as native Rapanui. Today, the island is considered part of the Valparaíso Region of Chile, and is referred to as Province Isla de Pascua. The geographic parameters of its iconic island-wide landscapes constitute the Rapa Nui National Park which was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995. Today, control over the national park has shifted from the Chilean government to the the Ma‘u Henua Indigenous Community, a local council made up the island’s traditional clan leaders. There is high community consciousness around recycling and sustainability, and there are active movements and initiatives that promote Rapanui self-determination, independence, and indigenous rights.

Hawaiians and the Māʻohi of Rapa Nui acknowledge the strong cultural ties of our common Polynesian heritage. The ʻAha Moananuiākea Consortium has established a Declaration of Kinship and Unity with Foundation Ao Tupuna, and NGO Toki Rapa Nui.

For more information on the ʻAha Moananuiākea partnerships with Rapa Nui, see the link below:

Rapa Nui Partnerships and Declarations

PHOTO GALLERY

Culture and History

https://www.sciencekids.co.nz/sciencefacts/earth/easterisland.html

This student-focused website includes general information on Rapanui people and culture.

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/715/

This official UNESCO webpage is dedicated to Rapa Nui and its distinction as a World Heritage Site.

The catastrophic loss of the forest, now largely believed to be cause by rats, was a serious threat to the ecology of the island. There was a real threat of losing the top soil effecting the agricultural production. The people of Rapa Nui employed lithic (rock) mulching to increase the productivity of their lands. They used two methods of mulching. The first was to build gardens of round rock walls called manavai (pictured above). The other was to disperse rocks across most of the island which retain the top soil and moisture.

Click the links below to learn more about lithic mulching on Rapa Nui:

https://planetpermaculture.wordpress.com/2014/02/05/easter-islands-ancient-gardening-practices/

This is a Planet Permaculture Article and video. Duration 12:33

http://troyoneasterisland.blogspot.com/2013/08/gardens.html

This a short blog entry regarding lithic gardening.

https://imaginaisladepascua.com/en/rapa-nui-culture/easter-island-mystery/

This Imagina Rapa Nui web page presents brief information on the birdman cult, Tangata Manu; an important island deity, Makemake; and the ancestral founder of Rapa Nui according to tradition, Hotu Matuʻa.

https://moevarua.com/en/the-arrival-of-the-first-polynesians-to-rapa-nui/

This short overview published by Moevarua of the arrival of the first Polynesians to Rapa Nui was written by Cristian Moreno Pakarati, a Rapanui historian and founder of Ahirenga Historical Research and the “Recollecting Rapa Nui Project.”

http://islandheritage.org/wordpress/?page_id=144

This five-page essay about Rapa Nui’s post contact history is presented by the Easter Island Foundation.

This five-page essay about Rapa Nui’s position in the prehistory of Polynesia was written in 1972 by Dr. Kenneth P. Emory of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum.

https://uhpress.hawaii.edu/title/rnj/

The Rapa Nui Journal (RNJ) is the official, peer-reviewed journal, of the Easter Island Foundation (EIF). The journal serves as a forum for interdisciplinary scholarship in the humanities and social sciences on Easter Island and the Eastern Polynesian region. To access an online repository of all of the past volumes of the Rapa Nui Journal (RNJ) go to the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Kahualike search engine site here.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015012116151&view=1up&seq=9

This is the Bernice P. Bishop bulletin 160 by Alfred Metraux published in 1940.

http://www.openboek.org/wp-content/uploads/2017

The Rapa Nui text of these stories is contained in ten notebooks, the original of which has been reported to be lost.

The Moai

https://www.easterisland.travel/easter-island-facts-and-info/moai-statues/

This is an Easter Island Travel page discussing the Moai.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7j08gxUcBgc&t=2165s

This in-depth Fall of Civilizations video illustrates newer theories that call into question narratives accepted for so long about the Māʻohi destroying their own ecology to build Moai. It further highlights Māʻohi ingenuity in overcoming the ecological disaster and their resilience in surviving the trials that came with foreign contact. Full video duration 1:43:08.

This Smithsonian Magazine article is about repatriation discussions at the British Museum regarding a moai statue taken from Rapa Nui in 1869.

https://imaginaisladepascua.com/en/rapa-nui-culture/ahu-easter-island-ceremonial-center/

Featured on this page created by Imagina Rapa Nui is a list of restored ahu, ancestral rock platforms associated with moai statues and traditional religious practices.

Environment

The official website for NGO Toki Rapa Nui “Our pillars are the School of Music, social and environmental protection, and the preservation of the ancestral Rapa Nui legacy.”

The official website for Foundation Ao Tupuna, a group dedicated to the rescue of ancient knowledge such as ancestral navigation and cultural projects related to the Rapanui people and culture.

This is a PBS video on the impacts of plastics and tourism on the environment of Rapa Nui. Duration 7:03

This article by The Conversation presents a few ideas of why the ecocide narrative (native Rapanui destruction of the environment) doesnʻt hold up.

Here is an Agencia EFE article about some of the efforts Rapa Nui has made to become self-sustainable and waste-free.

https://www.americanscientist.org/article/rethinking-the-fall-of-easter-island

This American Scientist article gives alternative reasons for the decline in Rapanui civilization and the natural resources of Rapa Nui.

https://eatingupeaster.com/trailer-1

Learn more about and watch the trailer of “Eating Up Easter”, a film by native Rapanui filmmaker Sergio Mataʻu Rapu. Framed as a cinematic letter to his son, the film explores the tensions within an island community facing the globalizing effects of tourism while trying to protect their culture, identity, and ways of life for future generations. Duration 2:10

https://kaiwakiloumoku.ksbe.edu/article/pacific-conversations-perspective-of-an-indigenous-filmmaker

See the Maonanuiākea Pacific Conversations interview with Sergio Mataʻu Rapu about his film Eating Up Easter. Duration 29:56

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=POAFav0Vo50

Here is a short video that shows some of the impacts of climate change on Rapa Nui. English subtitles. Duration 1:00

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/lgWx9gZdTD6uvw

This Google Arts and Culture site offers a brief introduction into the impacts of climate change on Rapa Nui and some of the efforts in the fight to preserve the island heritage.

https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2020/07/vaikava-rapa-nui

This is a brief Pew Charitable Trusts article that shows how the Rapanui people uphold tradition as guardians of the ocean.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/01/190110141707.htm

This Science Daily article explains the relationship between Moai and the natural resources of Rapa Nui.

Language

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC8_gYkhIkMNXjLzqmc-k5_w

The Cultura Rapa Nui youtube channel featuring videos that teach Rapanui language for children.

https://langsci-press.org//catalog/book/124

This book by Paulus Kieviet provides a comprehensive description of the grammar of Rapanui, the Polynesian language spoken on Rapa Nui (Easter Island).

https://en.unesco.org/courier/2019-1/rapa-nui-back-brink

A UNESCO article on the state of the Rapanui language and their efforts to overcome the challenges to preserve it.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/easter-island-rongorongo-tablets

This is an Atlas Obscura article about the unique Rapanui writing system known as “rongorongo.”

Polynesian Voyaging

http://archive.hokulea.com/rapanuiback.html

This is a log entry recording the first sighting of Rapa Nui in 1999 by the Hōkūleʻa canoe.

http://www.hokulea.com/landfall-20-years-ago-hokule%CA%BBa-raises-rapa-nui-sea/

This is a Polynesian Voyaging Society website article from 1999: “Landfall -- Hōkūleʻa Raises Rapa Nui From the Sea.”

http://www.hokulea.com/hokulea-officially-welcomed-rapa-nui-traditional-landing-ceremony/

The 2017 welcoming ceremony for the Hōkūleʻa in Rapa Nui is featured in this Polynesian Voyaging Society video.

Tāpati Festival

https://chile.travel/en/2021-rapa-nui-tāpati-festival-in-february

This is the Chile Travel site on the events of the 2021 Tāpati Festival.

https://galapagostravel.online/tapati-festival

This is the Galapagos Travel’s page brief explanations of the events of the Tapati Festival.

https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/tapati-rapa-nui-easter-islands-iconic-festival-in-images

This Lonely Planet Guide has a good overview of events held during the Tāpati Festival.

http://www.rapanui.net/tapati/historia.html

This Spanish and English language official site created by the Ilustre Municipalidad de Isla de Pascua provides up-to- date information and history on the annual Tāpati Festival in Rapa Nui, which is typically held in January or February.

https://www.facebook.com/TapatiRapaNuiOficial/

Follow the official Facebook page of the Tāpati festival for Spanish language writeups and media about this amazing annual experience.