Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kipi Brown

We were at a wedding reception last weekend. Very upper-crust Hawaiian. Valet parking, green lawns, white tents, two open bars, three impressive hui hīmeni taking turns on stage.

We were, therefore, more than a little surprised when the first of these groups included "Latitū" in its offering of music to bride, groom, and family. We were further taken aback when the second of these groups did the same with "Pua o Kāmakahala," and we were even more astonished when the third group opened its set with a rousing rendition of "Keyhole Hula."

"Hū," said some of the folks at our corner table, "kinda risky, yah!" "Where is Aunty Alice when you need her to pound her cane and utter the much-dreaded ‘hewa’?" All three songs, you see, are about infidelity. Not exactly positive fare for a celebration in which fidelity should be a cornerstone.

The conversation then took a Letterman-like turn. What are the ten least appropriate Hawaiian songs for a wedding reception? We brainstormed for a while, came up with a baker’s dozen, and whittled our choices down to the five that follow.

1. "Latitū." The haku mele (he is most often identified as Harry Swinton) compares himself to a sailor who thinks that he alone knows the "latitude" of his sweetheart’s affection. He discovers, however, that he is one of a multitude of pilots—"he nui a he lehulehu nā pailaka"—who have visited her harbor.

2. "Piukeona." The haku mele (an unidentified, late 19th century resident of Ka‘ū) insults the beautiful Pōlani, his soon-to-be former lover. She is reputed to have described his manhood as a skinny, part-Mexican banana, so he counters by comparing her womanhood to a meeting place of telephone wires and to a deeply furrowed island jutting into the sea.

3. "Pua o Kāmakahala." Katie Stevens I‘i compares her straying husband to the kāmakahala blossoms that line the walkway of their home. His interest in mea poepoe, "round things," has undermined their once-pa‘a relationship.

4. "Hula o Makee." William Ellis uses the metaphors of ships and treacherous waters to tell the story of an unfaithful wife and her jilted husband. The Malulani discovers the Makee, husband discovers wife, in flagrante dilecto—keeled over on a reef with helpful Hiram standing above her, paddle in hand.

5. "Mauna Loa." Helen Lindsey Parker takes on the persona of an upset lover who tells her beau to get lost—"Kū ‘oe hele pēlā"—because of his incessant wandering, absence, and inattention. Their affection, she says, is little more than the roach-eaten handkerchief that she uses to wipe off his pointy shoes. "Na‘u nō ia ‘oni ho‘okahi / Kahi pela a‘o kāua," she concludes; she’d rather go it alone in the bed they once shared.

Because we wanted to supply a little balance to our critique, some plus to counteract the minus, we also came up with a short list of definitely appropriate wedding songs. We set aside the obvious "Ke Kali Nei Au" and "Ku‘u Lei ‘Awapuhi," and settled, instead, on:

1. "Awaiāulu ke Aloha," (also known as "Waiulu"). Attributed to George Kaleiohi Sr. (and sometimes to Lala Mahelona), this haunting waltz speaks of love made fast by tying together ("awaiāulu ke aloha"), of intimacy that withstands the test of time ("kou pili hemo ‘ole i ke kau"), and of the unassailable rightness of their bond ("pono ‘oe pono pū ho‘i kāua"). The song offers its married audience a powerful double-perspective: newlyweds look forward with anticipation, grey-heads look back with tears of affirmation.

2. "Lae Lae." Bina Mossman’s mother composed this light-footed mele when Bina and her husband-to-be were still courting. Mom gives her stamp of approval to their relationship and offers the poetic benediction: "E ola mau loa / Ku‘u mau pua / A puka i ke ao / Mālamalama"—Long live my two flowers; may they thrive in the light of day and in the radiance of marriage.

3. and 4. "Kawohikūkapulani" and "Pua Malihini." Helen Desha Beamer composed these songs for her daughter, Helen Elizabeth Kawohikūkapulani "Baby" Beamer, and for Baby’s fiancé, Lt. Charles Dahlberg (the malihini of the second song). At the time, the couple was caught up in a whirlwind of parties, showers, and wedding preparations. Neither realized that Mom had set aside some quiet moments for herself, a tranquil space in which she was able to haku this beautiful, perfectly matched pair of bride-and-groom mele.

5. "Līhau." Kīhei de Silva and Moe Keale collaborated on this wedding song for their friends Mary Faurot and Damon Pescaia. Their old-sounding waltz explains how love has settled on bride and groom like a soft mist, a cooling Līhau rain at the pali’s highest point. The mele then invokes Makanikeoe, a guardian-god of peace and love. "E ukali mai ana ka la‘i / Ka hilina‘i a Makanikeoe / Eia lā ‘o Makanikeoe"—Contentment will soon attend you, the abiding trust of Makanikeoe; yes, here it is, the love of Makanikeoe.

Hawaiian weddings, we concluded over our second-or-so glass of fine, white wine, are as much in need of music police as they are of food, fashion, and decoration police. Probably more so. If we believe that our ‘ōlelo still retains the power of ola and make, then we must also believe that our choice of wedding songs will have an impact on the strength of the bonds that hold a couple together. Better, then, that we sing "e awaiāulu i ke aloha" than "eia kā, he nui loa a he lehulehu nā paialaka o ia awa kū moku ē."

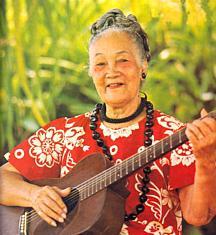

Alice Ku‘uleialohapoina‘ole Namakelua, 1974. In the "good old days" of the Hawaiian music renaissance, Aunty Alice was both loved and feared for the vigilance with which she guarded Hawaiian language, music, and dance. No one escaped her watchful eye and attentive ear—not disc jockeys, not emcees, not kumu hula, not guitar and ‘ukulele players, not even the most polished of singers. Everyone dreaded (and later swapped hilarious, spine-chilling stories about) the Aunty Alice phone call, the Aunty Alice glare, the Aunty Alice cane, and—worst of all—the Aunty Alice pronouncement of "hewa" on a slipshod performance. Aunty is no longer with us, and she is sorely needed in these days of ‘ai kū, ‘ai hele—of no restriction or restraint.