Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

Kīhei de Silva

Pulelo ha‘aheo ke ahi a Kaululā‘au! Be proud. Be very proud. The signal fires of Kaululā‘au blazed brightly on Sunday, November 7, at the Ritz-Carlton Kapalua Theater, having been fanned to new life by Keali‘iwahine Hokoana and Moses Goods III from the embers of W. N. Pualewa’s nearly forgotten "Ka Moolelo o Eleio," a Hawaiian language story that ran serially in Ka Nupepa Kuokoa from September 5 to November 21, 1863.

We know of Kaululā‘au from a variety of mostly abridged and sometimes mangled versions of his story. The son of Maui’s ruling chief Kāka‘alaneo, he is banished to Lāna‘i for his incorrigibly kolohe behavior. Because Lāna‘i is inhabited entirely by evil-gutted ghosts, the odds for the boy’s survival are low at best. But Kaululā‘au is far too quick a thinker and accomplished a liar for this ghostly horde. He sends the enemy to their deaths in thorny thickets and booming surf. He gets them ‘awa-drunk, seals their eyelids with ‘ulu sap, and torches their hale. He lures their leader, the sole survivor of this series of deceptions, into a pool of water where, depending on the version of the story, he either dispatches this Pahulu with a blow to the head or sends him packing for good. His work complete, Kaululā‘au builds a signal fire on a Lahaina-facing beach; Kāka‘alaneo investigates, discovers his son’s improbable success, and—depending on the version—either brings the new hero home in triumph and vindication or installs him as the new ruling chief of a soon-to-be-thriving Lāna‘i.

Pualewa includes Kaululā‘au’s Lāna‘i adventure in the context of a much larger story that includes lengthy recountings of the part played by the fleet-footed messenger ‘Ele‘io in the union of Kaululā‘au’s parents, of the arrangements leading up to this marriage, of Kaululā‘au’s early mischief-making, of the role played by the god Lono in the boy’s ghost-busting, of the repopulation of Lāna‘i under Kaululā‘au’s rule, of the disposition of the Maui kingdom following Kāka‘alaneo’s death, and of the numerous political activities in which Kaululā‘au was involved until the time of his own passing. The shape of Pualewa’s story is frequently non-Western: too many digressions, too many stories within stories, too little evidence of the neatly placed stepping stones of rising action, climax, and resolution, too much genealogy, too many moon phases and place-name sequences, too many lists of all kinds.

The shape of his story is, of course, Hawaiian. It is a lei of individually valued flowers strung together on the prophecy of Kūkamolimoliaola: "Kaululā‘au will indeed be a destructive child, but the land and all its districts will eventually be blessed by his strength, shrewdness, and incomparable deeds." Reading Pualewa is an exercise in e ho‘ohawai‘i ‘oe iā ‘oe iho. To appreciate Pualewa; you must not only read Hawaiian, you must accept his Hawaiian conventions of story-telling: his priorities, his pace, his interactivity, his digressions, and his lapses. His mo‘olelo requires that we attend to him as family gathered at his feet, not as patrons of TV, stage, and silver screen. If we accept these ground rules, Pualewa is delightful. If not, we let him fade into yellow dust in a 150-year-old newspaper. And we leave something of ourselves there, too.

We can be proud, very proud, that Keali‘iwahine Hokoana, the writer-director-producer of The Legend of Kaululā‘au, holds fiercely and lovingly to both the text and context of Pualewa’s story. Hokoana first read "Ka Moolelo o Eleio" in Kapulani Antonio’s fourth year Hawaiian language class. Additional study with Antonio’s husband Lōkahi (whose papa mo‘oka‘ao helped define for her the distinctive characteristics of Native Hawaiian storytelling) and Craig Gardner (who "taught me to write for the stage") led Hokoana to view the legend as an opportunity to create a stage play that would honor the kūpuna and help to revive a vanishing art:

The most difficult part . . . was to find a way to incorporate the characteristics of Native Hawaiian storytelling into a stage play. I spent many sleepless nights worrying over the details, because I knew that Kaululā‘au was born a real person, who had descendants, who had more descendants, who live today. I wanted to honor his memory and the memory of all those portrayed in the show. And, just as importantly, I wanted the art of Native Hawaiian storytelling to be reborn. I wanted this ancient story to come to life, the way Pualewa intended. Our mission is to preserve and perpetuate Native Hawaiian folklore by resurrecting ancient legends through storytelling.

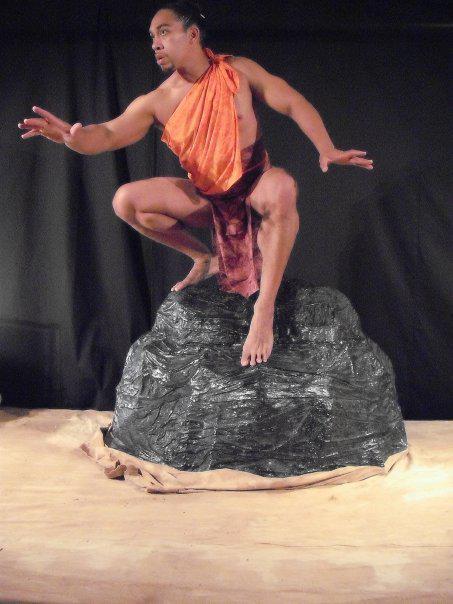

Hokoana’s play is mostly in English (in large part, carefully and elegantly translated from the Hawaiian), but it preserves enough equally elegant Hawaiian to retain the flavor of Pualewa’s ‘ōlelo. Hokoana’s play reduces Pualewa’s 12-chapter, 18,000-word original to three fleet-footed acts, but it remains remarkably loyal to the scope, sequence, and detail of its parent text. Hokoana’s play is layered with meaning (it asks us, for example, to give serious thought to models of Hawaiian leadership and Hawaiian coming-of-age), but it folds these meanings unobtrusively into a story that captivates the children in the audience as completely as it does their parents. Hokoana’s play relies on a single actor, Moses Goods III, in the role of storyteller, but his telling is far from static or one-dimensional.

Goods, in fact, is no less a trickster than Kaululā‘au; he is capable of extraordinary transformations into and out of each of the nine characters he shares with us. He greets us in dignified Hawaiian and begins his story in traditional fashion, with genealogy: "‘O Kāka‘alaneo ke kāne, ‘o Kelekeleiōkaula ka wahine. Noho pū lāua a hānau ‘ia ‘o Kaululā‘au." He sprints through the theater as ‘Ele‘io, naming the districts as he goes, the ravenous demigod ‘Ā‘āhuali‘i hot on his heels: "from Ko‘olau to Hamakualoa, to Hamakuapoko, to Wailuku, to Kama‘alaea, to the cliffs of ‘A‘alaloloa, and down to Papalā‘au, to Ukumehame, to Olowalu, to Awalua . . ."; then he pauses, sips from his water gourd, and resumes his story-teller narrative. As Kāka‘alaneo, he loses his royal cool over the prospect of damaging the feather cloak of his wife-to-be, and he screeches in near Gollum-voice at his warriors:

E mālama ‘oukou i ke ola o ‘Ele‘io, ‘a‘ole make kiola i loko o ka imu ahi, no ka mea, ua lawe mai kēlā i ka ‘ahu‘ula, ua minamina akula na‘e au i ka pau ‘ana iā ‘oukou i ka haehae, no laila, e ola ‘o ‘Ele‘io ‘a‘ole e make . . .

He dodders and wheezes as the prophet Kūkamolimoliaola who warns against killing or even beating the kalo-yanking Kaululā‘au "because the land will be blessed by his deeds." He plays a hulking, fee-fie-fo-fum Pahulu: "Where did you sleep the night before?" And then he shape-shifts, in the blink of an eye, from monster to innocent boy: "In the puakala grove . . . Perhaps you went to the big puakala grove. I was in the little one." At play’s end, Goods accomplishes his last shape-shifting sequence; as the aged and infirm Kaululā‘au, he drags himself forward, hunched over his walking stick, and refuses to accept Lono’s invitation to live as a god in the heavens of Hālaulani:

Inā ho‘i paha wau e ‘ae aku iā ‘oe e ho‘i aku i ko ‘oukou wahi, if perhaps, I consent to go to that place, a laila, pilikia ho‘i ko‘u ‘ohana a me ko‘u lehulehu. [My family and my people will be in trouble.]

Goods then rises to his full height and quietly concludes: "And so he stayed. Pipi holo ka‘ao." Goods, Hokoana, and Pualewa are done with their mo‘olelo, but this is where we realize that the play’s final and most important transformation has been worked on us. We are no longer an audience in a theater. We are a family in our own parlor, in our own back yard, on tūtū wahine’s own moena lauhala. We have just shared a story of our own kūpuna, and it makes us proud, very proud, of who we are.

If Goods is a trickster, he is not alone. Hokoana, a real-world mother of three, began with "$1800 and a Capital One Master Card." She enlisted a small army of family and friends—including Grandma Bernice as costume designer, Aunty Donella as set designer, and husband Michael Gormley as prop designer—to mount her unlikely, against-most-odds production. And she had the good fortune of connecting with Clifford Naeole, Hawaiian cultural adviser at the Ritz-Carlton, Kapalua. Naeole is well-known for his commitment to "immersing this five-diamond hotel in our five-diamond culture," a commitment that includes requiring all Ritz-Carlton, Kapalua employees to begin their tenure at the hotel by viewing Elizabeth Lindsey Buyers’ "And Then They Were None." I ka pupu‘u nō a ho‘olei loa—without hesitation, quick as a flash—Naeole extended an invitation to Hokoana and the Legend of Kaululā‘au: "Why not do it here at the Kapalua Theater?"

Naeole’s invitation was neither cautious nor manini-minded. It is for a year of Sundays, two shows per Sunday. "Hawaiians," he explains, "aren’t here at this hotel to put lei on your neck, hand you a mai tai, and say ʻbus to the left, bus to the right.’ We were philosopher-farmers; we are proud and intelligent. This play shows our depth; it promotes a positive, authentic image of our people."

The Legend of Kaululā‘au—the story of a trickster with a conscience, produced and hosted by tricksters of equal skill and conscience—began its 12-month run on Sunday, November 14. Shows are at 4:00 and 6:30 p. m. For tickets and information call toll free 1-888-808-1055.

Pipi holo ka‘ao. May the "sprinkled" tale, the well-told tale, travel far and wide.

Moses Goods III, Storyteller of Kaululāʻau, began his acting career in 1999 at the University of Hawaiʻi’s Kennedy Theater. Since then, he has played a number of challenging roles on Honolulu stages. Some of these include the title roles in Shakespeare’s Coriolanus and Mammet’s Edmond, Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust, Wolf in August Wilson’s Two Trains Running (for which he received a Poʻokela Award), and Wayne in Lee Tonouchi’s Gone Feeshing.