Digital Collections

Celebrating the breadth and depth of Hawaiian knowledge. Amplifying Pacific voices of resiliency and hope. Recording the wisdom of past and present to help shape our future.

contributed by Nanea Armstrong-Wassel [Ho‘okahua]

AN OVERVIEW

Kāhili, or feather standards, are traditional symbols of Hawaiian aliʻi. Representing the sanctity and mana of the chief, kāhili were borne by favored attendants (paʻa kāhili or lawe kāhili) either preceding or following the aliʻi. Kāhili were used in different social settings to signify the presence of a chief, including in battle, occasions of state, large gatherings, and other events. Wherever they accompanied the chief, kāhili instilled a sense of dignity and regal presence.

Kāhili were considered sacred and were treated as members of the aliʻi’s family, a symbol of royalty imbued with the owner’s mana and enhancing his or her spiritual protection. They were given personal names which were often associated with the aliʻi they belonged to or were a physical description of the kāhili itself.

The kāhili represented the royal household and had kahu (caretakers) who would ensure it was properly cared for, as one would look after a child. The kahu also ensured that when the kāhili was not in use, its feathers were removed, bundled, wrapped in kapa, and placed in calabashes for safe keeping and future use.

When worn feathers needed to be replaced, the kāhili retained its name if the original pole was reused.

Upon the death of an aliʻi, his or her kāhili retained the mana of its owner which was then passed on to its next bearer, in essence, taking on the spirit of the aliʻi to whom it belonged.

Prior to feather standards, the stalk and leaves of the lāʻī (tī leaf) were used as kāhili, as lāʻī itself represents spiritual mana and purification. The long-stalked lāʻī could be seen from far away and alerted makaʻāinana that someone of chiefly rank was approaching so they could prepare appropriately. Rainbows that appeared vertically were called “ānuenue kāhili,” hōʻailona that an aliʻi was in close proximity.

In Hawaiʻi: The Royal Isles, Roger Rose writes:

Before Hawaiian chiefly tradition had been greatly changed by missionary influence, the Reverend C. S. Steward (1828, pp. 117-118) witnessed an impressive state procession in May 1823, commemorating the late Kamehameha I. ‘So far as the feather mantles, helmets, coronets [lei] and kahilis,’ he wrote, ‘I doubt whether there is a nation in Christendom which…could have presented a court dress and insignia of rank so magnificent as these… There is something approaching the sublime in the lofty noddings of the kahilis of state as they tower far above the heads of the groups whose distinction they proclaim: something conveying to the mind impressions of greater majesty than the gleamings of the most splendid banners I ever saw unfurled.’

MAKING OF THE KĀHILI

Thousands of feathers were requried to complete even one kāhili, and the rank and mana of a chief could be defined by the types of feathers used to make his or her feathered objects. Feathers were collected over many years, and only chiefs of the highest rank would be able to accumulate enough to make large capes or numerous kāhili. During the taxing of the makahiki season, the aliʻi nui or mōʻī (highest chief on the island) took the feathers accumulated in each ahupuaʻa and kept or shared them as he or she saw fit. In traditional Hawaiian society, the lower-ranking chiefs would probably not have demanded such ʻauhau (offerings), as this could be seen as a challenge to the higher ranking aliʻi.

Bird-catching in traditional Hawaiian society was an art. The bird would not be killed for its feathers; instead, the skilled kia manu (bird catchers) would smear a sticky, sap-like substance on a branch and wait for a bird to land. Upon landing, the bird would be briefly immobilized and the kia manu would then take a few feathers from the bird, clean him, and release him. This pain-staking process is why only the highest-ranking chiefs could be afforded the luxury of certain types of feathers. The mamo and ʻōʻō feathers were reserved for higher ranking aliʻi, while chiefs of lesser rank used feathers from the moa (chicken) or other birds.

Here is a description of the traditional kāhili-making process:

The hulumanu (feathered portion) was made of thousands of feathers. Several feathers were bundled and tied together with olonā fiber forming the ʻuo.

Numerous ʻuo were incorporated at the peʻa (tips) of branches, called ʻau. The core of the ʻau was made with the roots of the ʻieʻie vine or nīʻau (midribs of coconut leaves). They came together to form the koʻo (stalk), which in turn was attached to the kāhili staff.

ʻAu were then lashed to the upper portion of a pole, beginning at the top and working down in a continuous spiral using olonā or other cordage.

The kumu (pole) was often, though not exclusively, made of kauila wood. Some of the more elaborate ones were made from stringing disks of tortoise shell, bone, or ivory on a slender core of kauila wood or whale bone.

“Leg bones were usually used to fashion these disks and it was considered an honor to have one’s bones used in a kāhili handle, in contrast to the insult when bones were used as fishhooks or to inlay spittoons.” (Buck, p.579)

The pāʻū (skirt) at the bottom of the hulumanu, pāpale (cap) at the top of the kāhili, and streamers originally made of kapa were all optional trim.

photo credit: S. Conant

Kāhili branch types (left to right): unforked (red-tailed tropicbird central tail feathers), forked (peacock eye feathers), and double-forked (Hawaiʻi ʻōʻō axillary feathers).

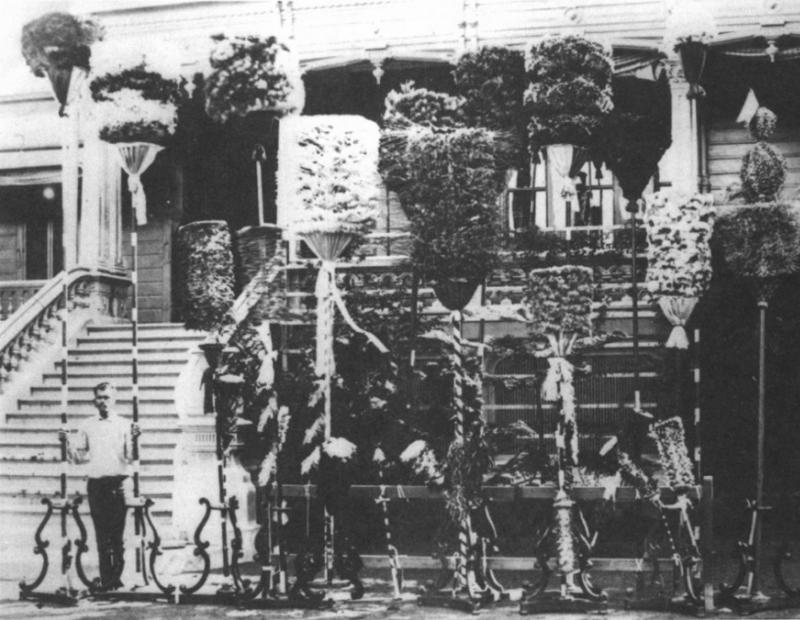

photo credit: W. T. Brigham, Bishop Museum Archives

Some of the Kamehameha family kāhili assembled in front of Keōua hale, the house of Keʻelikōlani and Bernice P. Bishop, c. 1890. All of these kāhili are preserved in the Bishop Museum.

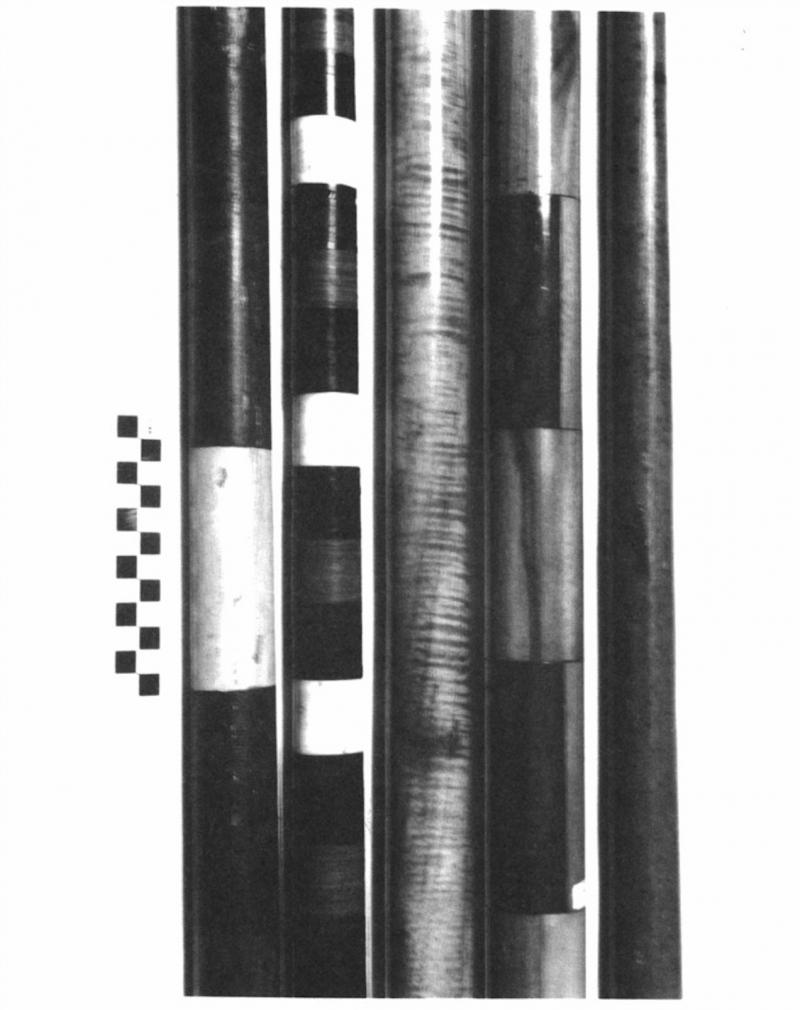

photo credit: E. P. Kjellgren

Kāhili pole types (left to right): painted conifer, ivory and light- and dark-colored turtle shell, koa wood, laminated native woods, reused kauila spear.